The Emerald Tablet of Hermes enters the documented historical record far later than is commonly asserted in popular esoteric discourse. While modern hermetic and occult traditions frequently situate the tablet within a mythic antiquity—often projecting it into Atlantean prehistory or imagining it as a primordial cornerstone of alchemical doctrine—the earliest verifiable attestations do not derive from pharaonic Egypt or the intellectual milieu of classical Greece. Instead, the text appears within early medieval Arabic and Sufi hermetic literature of the 8th–9th centuries CE, where it is already presented as an object of immense antiquity. By this stage, it has been fully mythologized: a green, imperishable stone engraved with universal principles and attributed to Hermes Trismegistos, a syncretic figure merging the Egyptian Thoth with the Greek Hermes. Within this medieval framework, the Tablet also becomes increasingly intertwined with emerging theories of the philosophers’ stone, not as a literal transmutational substance but as a conceptual emblem of perfected knowledge—the distillation of cosmic order into a single, immutable medium.

This historical discontinuity raises a central historiographic problem:

If the Emerald Tablet first surfaces fully formed within medieval hermeticism, what earlier material practice, textual tradition, or administrative technology generated the memory that crystallized into this legend?

Pursuing this question requires a retrospective analytic approach—not one that follows speculative Atlantology or the romanticized intellectual genealogy of Hellenistic Alexandria, but one that examines the deeper administrative and theological systems that shaped how premodern societies materialized authority. Such systems governed the production, circulation, and sanctification of inscribed media, and thus determined how cosmology, law, and political order were encoded across time.

The Medieval Moment: How an Object Became a Myth

The earliest Arabic Hermetic texts do more than simply reference the Emerald Tablet—they frame it as a relic already embedded in a deep civilizational memory. By the 8th–9th centuries, when these sources emerge, the Tablet is treated not as an isolated curiosity but as the surviving fragment of an older epistemic order whose origins had already receded beyond visibility. This framing appears prominently in the Kitāb Sirr al-Khalīqa and related works attributed to pseudo‑Apollonius.

These texts describe:

- a green, incorruptible stone sealed within a subterranean vault beneath a sacred structure, echoing traditions preserved in temple‑archive literature such as the Tablets of Destiny,

- an inscription that compresses cosmology, kingship, ritual authority, and metaphysical law into a single, aphoristic statement, consistent with the epitomic style of the Corpus Hermeticum,

- a transmission lineage—Hermes → Agathodaimon → Balinas (Apollonius of Tyana)—that parallels the synthetic genealogies preserved in late antique works such as the Life of Apollonius and the broader Hermetic biographies circulating in Greco‑Egyptian philosophical texts.

Within Islamic esotericism, the Tablet undergoes a decisive conceptual transformation. It no longer functions as something that might plausibly have been an administrative object or dynastic decree. Instead, it becomes a cosmic artifact—a crystallized remnant of primordial wisdom whose authority lies precisely in its resistance to historical placement. This shift parallels the treatment of the philosophers’ stone in early Arabic alchemical corpora such as the Book of the Secret of Creation and the Emerald Formula traditions, where the stone is framed not as a literal reagent but as a symbol of perfected, totalized knowledge.

This conceptual elevation is not a medieval invention ex nihilo. It reflects the long afterlife of objects whose original bureaucratic, ritual, or political functions had been forgotten. What medieval authors preserve is the residue of an older material regime—a memory of authoritative inscribed media whose contexts had dissolved, leaving only a sense of their enigmatic power. Comparative materials from Mesopotamian and Egyptian archive systems—such as the House of Life papyri, temple deposit inscriptions, and multilingual stelae—demonstrate how such memory could persist even after the artifacts themselves vanished.

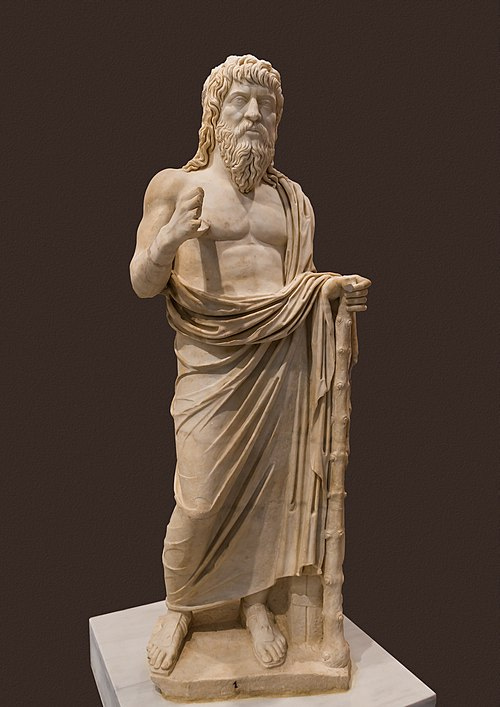

It is in this discursive environment that Apollonius of Tyana reenters the narrative. He is the earliest figure in antiquity explicitly associated with the discovery of a hidden inscribed tablet, as narrated in the Life of Apollonius. His legend becomes the structural bridge linking late antique miracle lore, Near Eastern archive traditions, and the fully mythologized Hermeticism of the medieval Islamic world. Apollonius becomes the human conduit through which the remembered power of an earlier administrative–ritual apparatus is transformed into the myth of the Emerald Tablet.

Apollonius, Cappadocia, and the Problem of Origins

The tradition that Apollonius of Tyana uncovered a sacred tablet in a concealed chamber—variously described as a cavern, a sealed ritual crypt, or even a tomb containing the preserved body of Hermes—cannot be understood in isolation. It must be situated within the layered ritual ecology, geopolitical volatility, and epistemic pluralism of his homeland. Cappadocia, positioned at the hinge-point between Anatolia, Persia, and the Levant, was not merely a backdrop but an active generator of hybrid religious memory. Its landscape and cultural dynamics shaped how a narrative of hidden tablets could emerge, take root, and gain authority.

Cappadocia was characterized by several distinctive features that directly sharpen the plausibility and rhetorical power of the Apollonian tablet legend:

- extensive subterranean tunnel networks, rock-cut complexes, and multi-tiered underground cities used for ritual incubation, defensive retreat, monastic withdrawal, and esoteric instruction,

- a ritual pluralism in which Greco-Anatolian cults (Zeus Sabazios, Artemis Anaitis), Iranian priestly traditions linked to Mithraic and Magian lineages, and indigenous fertility and chthonic cults all coexisted and intermingled,

- proximity to and interaction with Levantine and Mesopotamian scribal cultures, whose archive traditions—tablet burial, temple deposits, foundation inscriptions—provided a recognizable template for narratives involving concealed wisdom.

By late antiquity, Apollonius had undergone a profound narrative transformation. He was no longer merely a philosopher in the Pythagorean lineage; he had been recast as a theurgic counter-Christ, a wandering miracle-worker whose biography in the Life of Apollonius deliberately mirrors, rivals, and destabilizes Christian hagiography. In such a charged ideological environment, the report of a hidden tablet is not an incidental episode but a strategic literary device. It anchors Apollonius in a lineage of primordial authority, positioning him as the inheritor of a wisdom tradition older than Greece, older than Persia, older even than the biblical patriarchs.

The story achieves its persuasive force because it draws upon Cappadocia’s material realities—underground sanctuaries, burial caches, cryptic inscriptions—and its symbolic economy, in which subterranean spaces were understood as places of revelation, ancestral power, and divine encounter. A tablet discovered in such a space would not read as metaphor; it would register as the recovery of something fundamentally pre-exilic, pre-imperial, or pre-literate.

Yet even if we accept the possibility that Apollonius encountered a physical inscribed object, the legend provides almost no information about its genre, function, or institutional context. Was it funerary? Administrative? Oracular? Foundational? The ambiguity signals that what survived in memory was not the content of the inscription, but the concept of an authoritative inscribed medium: hidden, potent, sanctioned by antiquity, and capable of legitimizing a charismatic figure.

To identify what such an artifact could plausibly have been, one must move far beyond the Apollonian horizon. The deeper prototypes for an object like the so‑called Hermetic tablet—objects that fuse governance, cosmology, and sacred authority—emerge nearly 1,500 years before Apollonius, during the transformative rise of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, when the very notion of a state-sanctioned cosmic inscription first crystallized in material form.

Egypt’s Expansion and the Birth of Administrative Cosmology

The 18th Dynasty (ca. 1550–1290 BCE) marks not simply a major political turning point but a profound reorganization of Egypt’s epistemic architecture. This was the moment when Egypt ceased to be a linear river kingdom and reconstituted itself as a continental intelligence system, extending from the Fourth Cataract to the northern Levant. Empires create not only armies and taxation structures—they create new forms of cognition. And the 18th Dynasty forced Egypt to confront, for the first time, the administrative problem of governing difference at scale.

This imperial expansion introduced challenges unprecedented in earlier Egyptian history:

- populations speaking mutually unintelligible languages, requiring mechanisms for translation, mediation, and record-keeping,

- local legal traditions that varied sharply across Nubia, Canaan, and Syria-Palestine, demanding a central apparatus capable of negotiating conflicting norms,

- foreign priesthoods and cultic infrastructures, which required careful theological integration to avoid destabilizing the ideological foundations of kingship,

- long-distance communication chains, linking fortified outposts, garrisons, and vassal courts across thousands of kilometers.

The Egyptian state had never before been forced to process this magnitude of heterogeneity. The response was not linguistic assimilation—Egypt did not adopt cuneiform scripts or shift to Akkadian administration, despite its widespread diplomatic use. Instead, the state doubled down on its own semiotic sovereignty.

Egyptian writing had always been tripartite—a fusion of phonetic values, semantic determinatives, and ideographic imagery. But under the pressures of empire, this structure hardened into something far more ambitious: a totalizing cognitive system. Writing became a model of the universe itself—a structured environment in which political hierarchy, cosmic order, and bureaucratic procedure were mutually reinforcing.

This is what scholars increasingly describe as administrative cosmology: a unification of governance and metaphysics. Within this system, an inscription was never merely textual. It was a binding of worlds—ritual, civic, celestial—into a single material act.

The maturation of this cosmology is visible in architectural, ritual, and diplomatic innovations: the expansion of royal titulary, the standardization of temple relief programs, and the development of a pan-imperial visual vocabulary legible from Thebes to Megiddo. Each of these transformations reflects a deeper truth: the state was learning to think in layers, to encode reality through structured multiplicity.

But this intellectual trajectory would only reach its full crystallization when Egypt’s writing system encountered two additional forces:

- the multilingual imperial logic of Persia, and

- the administrative rationality and legal universalism of Greece.

The collision of these traditions did not dilute Egyptian cosmology—it amplified it. The fusion produced something new in world history: the multilingual decree tablet, an object that united sacred authority, civic law, and imperial communication within a single engineered medium.

This class of objects—distributed, standardized, and semiotically layered—forms the direct technological and conceptual precursor to what would later be mythologized as the Emerald Tablet. They are its institutional ancestors: the points where writing, rulership, and cosmic order converged into a single, authoritative surface.

Persia and the Trilingual Precedent (A Formal Prototype, Not a Functional One)

The Achaemenid Persian Empire introduced one of the earliest systematic deployments of trilingual monumental inscriptions, with the Behistun Inscription standing as the canonical example. Carved in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian Akkadian, Behistun is often described as the “Rosetta Stone of cuneiform,” but its function was radically different from the later Egyptian trilingual decrees it superficially anticipates.

Persia’s multilingual inscriptions established the visual grammar and formal architecture of imperial multilingualism, but their logic was fundamentally performative, not administrative. These texts were expressions of imperial self‑theorization, designed to broadcast a unifying message to a linguistically fragmented empire. Their primary functions were:

- propagandistic projection, declaring the king’s legitimacy through divine sanction and narrative control,

- imperial identity construction, articulating the king as a universal sovereign recognizable across cultural boundaries,

- territorial assertion, marking landscapes with ideological messages rather than practical directives.

Yet for all their monumental power, Persian trilingual inscriptions did not operate as instruments of governance. They were not used for:

- civic or municipal decrees,

- temple or cultic legal codification,

- bureaucratic regulation or provincial administration.

They were static proclamations, not circulating legal instruments. Their visibility mattered more than their legibility; their presence mattered more than their use. They proclaimed empire but did not administer it.

To put it differently: Persian multilingualism was imperial theater, not imperial infrastructure.

This distinction is crucial, because it clarifies what the Persian precedent did and did not accomplish. It provided the template—the idea that a single object might speak in multiple imperial voices—but it did not produce the technology necessary to integrate sacred authority, administrative law, and multilingual communication into a unified system.

The next step required a different political ecology—one where:

- an ancient tripartite writing ideology (Egypt),

- an inherited monumental multilingual tradition (Persia), and

- a newly introduced administrative‑legal rationality (Greece)

could converge.

Such a convergence was impossible in Persia, because Persian inscriptions—however multilingual—remained tied to a unidirectional model of kingship, not a distributed administrative network. They were declarations, not devices.

The full transformation of multilingual inscription into a functional tool of governance—capable of binding cosmic order, civic authority, and imperial law into a single semiotic surface—would only occur later, and only in one place:

Greek‑ruled Egypt.

Ptolemaic Egypt: The Invention of the Trilingual Decree Tablet

When Alexander’s conquest placed Egypt under Ptolemaic rule, the region did not merely shift from one dynasty to another—it entered a new epistemic regime. The result was a profound semiotic, administrative, and cosmological fusion, forged through the collision of three mature systems of thought:

- the Egyptian tripartite writing ideology, where inscription operated as a theological engine mediating the relationship between cosmos, kingship, and ritual order;

- the Persian monumental multilingual precedent, which had demonstrated that empire could articulate itself through multiple linguistic registers simultaneously;

- the Greek administrative‑legal rationality, which introduced bureaucratic standardization, civic codification, and a new architecture of governance.

This convergence did not produce a simple hybrid. It produced an innovation with no precedent in the ancient world:

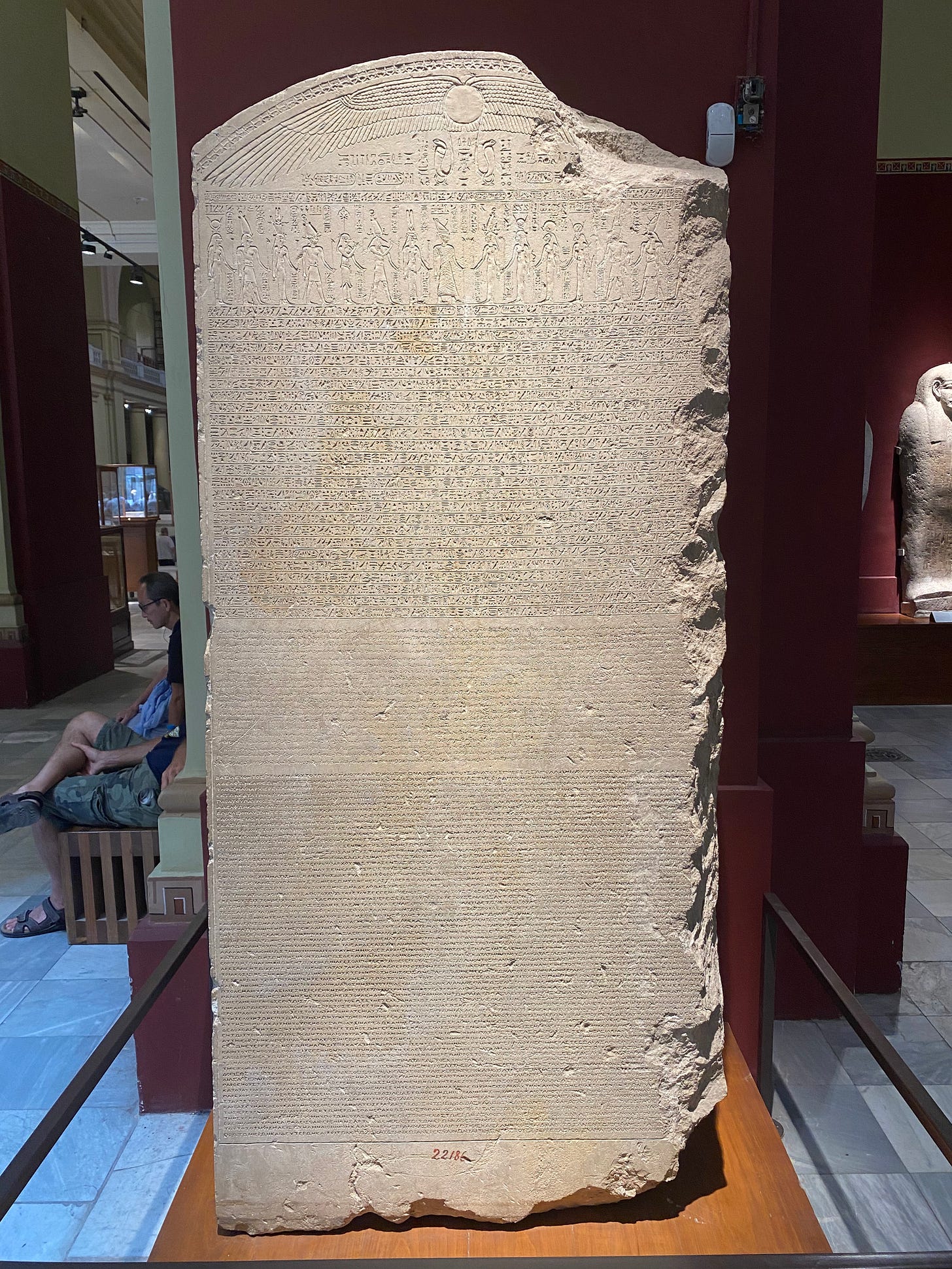

The Trilingual Decree Stela

Each decree spoke across three linguistic and metaphysical strata:

- Hieroglyphic — the sacred register, addressing gods and eternity, encoding cosmic legitimacy;

- Demotic — the civic-administrative register, legible to Egyptian officials, scribes, and everyday subjects;

- Greek — the juridical-imperial register, binding Egypt into the Hellenistic political and legal system.

These were not ornamental or ceremonial artifacts. They were semiotic machines, engineered to operate simultaneously as:

- law, in the Greek juridical sense;

- cosmological proclamation, in the Egyptian theological sense;

- imperial charter, in the administrative sense.

Their force derived from their triple ontology—each tablet fused divine order, social order, and imperial order into a single communicative surface. This was governance made material.

And crucially, these stelae were not unique monuments. They formed a distributed network of power. Each decree was replicated and disseminated across Egypt’s nomes, the provincial districts whose later echoes survive in the Catholic diocese structure. The result was a grid of synchronized cosmic‑legal authority nodes, extending Thebes’ theological legitimacy into every corner of the kingdom.

This system made the trilingual stelae the operating system of Ptolemaic governance—a platform on which divine sanction, civic regulation, and imperial command converged. They unified a multiethnic, multilingual population by giving each group access to a different facet of the same authoritative message.

Equally important is the site of their production: the scribal houses of Hermopolis, the cult center of Thoth, patron of writing, mathematics, arbitration, and cosmic equilibrium. Hermopolis was not a mere workshop. It was an ideological reactor, where inscriptions were not only crafted but consecrated within the mythic lineage that would later crystallize as Hermes Trismegistos. Producing a decree there anchored it within Egypt’s deepest semiotic infrastructure.

In this light, the trilingual decree stelae were not passive objects but cosmic‑administrative instruments. They represent the culmination of Egyptian scribal theology, Persian imperial communication strategies, and Greek bureaucratic rationality—a fusion so potent that later generations could only reinterpret it through myth.

This is why the trilingual stela stands as the closest historical analogue to the legendary Emerald Tablet. It is the material precursor to the idea of a single, dense, world‑ordering inscription—a surface where cosmic truth, legal authority, and imperial order were not merely written but engineered into being.

The Power and Destruction of the Tablets

The trilingual decree stelae derived their force from the unprecedented fact that they bound three distinct realms of authority—the divine, the civic, and the imperial—into a single communicative surface. No other inscriptional medium in the ancient world occupied so many ontological registers simultaneously. In hieroglyphic, the stela addressed the gods and asserted cosmic legitimacy; in demotic, it spoke to Egyptian administrators and priesthoods, articulating the normative order of daily governance; in Greek, it participated in the legal and diplomatic architecture of the Hellenistic world. Each stela, therefore, was not simply a document. It was a material consolidation of sovereignty, an instrument through which the state rendered its total worldview—cosmic, social, and bureaucratic—into durable form.

Objects capable of condensing such authority inevitably became politically unstable in moments of transition. As Egypt passed successively through Ptolemaic, Roman, Christian, and Islamic regimes, each new order faced the same dilemma: these stelae were inseparable from the cosmology of the system they had been designed to uphold. Their continued visibility threatened to anchor the legitimacy of a regime that no longer existed. And so, one by one, they were targeted. Some were smashed in deliberate ritual acts meant to sever the prior cosmology; others were interred beneath temple floors, their authority contained rather than obliterated; still others were cannibalized into masonry, their inscriptions rendered unreadable even as their physical presence remained embedded within the architectural fabric of later structures. A minority were sealed intact within temple vaults—protected, paradoxically, because they were too potent to destroy without consequence.

This wide-scale dispersal and mutilation produced what might be called a cultural palimpsest of absence. Late antiquity did not inherit the stelae themselves so much as the memory of their disappearance—a memory that resonated with other deep mythic structures across the ancient Near East. Mesopotamia preserved the notion of cosmic authority inscribed on tablets that could be stolen, shattered, or reclaimed—the Tablets of Destiny. Israelite tradition spoke of the breaking of the Tablets of the Law, a symbolic rupture of covenantal order. Egyptian mythology itself was structured around the dismemberment and reassembly of Osiris, whose fragmented body became a metaphor for cosmic destabilization and restoration.

These traditions share a common logic: world‑ordering objects must fracture when the order they sustain collapses. Destruction becomes a political theology of transition—a way of neutralizing the prior regime’s cosmological apparatus while creating the conditions for a new one to emerge. The shattering of such objects is never merely destructive. It is an act of epistemic sanitation, clearing the semiotic field so that power can be rewritten.

Thus, by the time the late antique and early medieval imagination tried to make sense of Egypt’s vanished stelae, what survived was not the administrative function of the tablets but the aura of their former potency. They were remembered not as legal instruments but as occult relics—enigmatic, powerful, and irrevocably tied to a lost cosmology. In this environment, the idea of a single, indestructible tablet—green, eternal, engraved with primordial wisdom—could emerge as a symbolic condensation of an entire class of vanished artifacts.

The Emerald Tablet, in other words, was born from the afterglow of destruction. It crystallized from the cultural memory of a world in which cosmic authority had once been written on stone, distributed across a kingdom, and later shattered to prevent its misuse. The legend is not a fantasy grafted onto history; it is history’s own residue, distilled into myth.

Survival Through Legend: Alexander → Apollonius → Arabs → Napoleon

By the time the trilingual decree tablets had vanished from the physical landscape of Egypt, their memory survived only in refracted, increasingly mythologized form. What emerges across antiquity and late antiquity is not a linear historical record but a chain of narrative custodianship, in which each era reinterprets the vanished tablets through its own symbolic lexicon. The result is a transmission arc that moves not through documents, but through figures—each one serving as a conduit for a different stage of the tablet’s metamorphosis.

Alexander the Great

In the fourth century BCE, Alexander’s visit to the Oracle of Siwa already positioned him within the mythic geography of Hermetic Egypt. Later traditions insist that he received a priestly initiation and that, somewhere in the desert west of the Nile, he encountered a tomb associated with Hermes. Medieval writers would later amplify this memory into the claim that Alexander found a tablet of cosmic wisdom within that tomb. Whether or not any such object existed, the association is striking: Alexander becomes the first imperial figure to be linked with the recovery of a primordial inscription.

Apollonius of Sana

Several centuries later, Apollonius inherits and intensifies this motif. His biography places him in subterranean chambers, conversing with priests, sages, and spirits of antiquity. Reports of his discovering a concealed tablet recast him as the philosophical heir to Hermes, transforming a Pythagorean wonder-worker into a Hermetic intermediary. Through Apollonius, the memory of Egypt’s administrative tablets crosses into the domain of esoteric lore, stripped of bureaucratic context and reimagined as a relic of supernatural wisdom.

Arabic Hermeticists (8th–9th c.)

When Hermetic texts surface in the Arabic Middle Ages, the transformation is complete. The tablet is no longer described as a decree, nor as a royal inscription, nor even as a funerary artifact. It has become a green, eternal stone, a crystallization of cosmic truth. Yet these writers also preserve key structural features—its discovery in an underground vault, its association with Hermes, its status as a compressed articulation of the universe—that align uncannily with the Egyptian trilingual decree tradition. The Arabic Hermeticists do not invent the tablet; they inherit the afterimage of something real, long destroyed.

Napoleon’s scholars (1799)

The next great shift occurs not through legend but through archaeology. Napoleon’s savants, digging at Fort Julien, unearth what would become the Rosetta Stone—the single best-preserved exemplar of a trilingual decree tablet. At the moment of discovery, the stone’s significance was entirely opaque; its hieroglyphic and demotic sections were unreadable, its connection to Memphis unknown. Only through later decipherment did its true nature emerge: it was precisely the kind of object that Alexander or Apollonius would have encountered in fragmentary or concealed form.

Seen from this vantage, the Rosetta Stone is not merely a breakthrough in linguistics. It is the last surviving witness of a vanished administrative‑cosmic technology, the sole intact representative of a class of objects that once structured an entire kingdom’s relationship to divinity, law, and empire.

It stands today not as an isolated monument, but as the material ancestor of the Emerald Tablet myth itself—proof that the legends did not arise from nothing, but from the long memory of a real inscriptional system whose physical corpus has otherwise disappeared.

Multiplication: The 20th-Century “Emerald Tablets”

By the early twentieth century, the figure of the Emerald Tablet entered a new phase of its afterlife—one defined not by singularity but by proliferation. What earlier centuries had remembered as a lone, opaque artifact suddenly fractured into an expansive esoteric genre, reproduced across Theosophical treatises, occult pamphlets, Rosicrucian manuals, quasi-Hermetic discourses, and eventually the broader metaphysical literature of the late modern period. Each text claimed descent from the primordial source; each spoke in the cadence of revelation; each presented itself as a recovered shard of a hidden world-system. The Emerald Tablet, once imagined as a solitary monolith of cosmic truth, now appeared in dozens of incompatible voices.

What looks, on the surface, like a modern eccentricity reveals something far more structurally significant. The Ptolemaic trilingual decree system—the historical substrate of the Hermetic myth—was never a single object. It was a distributed network of tablets, each node calibrated to synchronize cosmic order with administrative law, each positioned in a specific nome, each reproducing the same semiotic architecture at a different geographic and political scale. The ancient system was inherently multiple, even as later memory compressed it into a solitary emblem.

When the political regimes that upheld the trilingual decree apparatus dissolved, the tablets met divergent fates—shattered, buried, dismembered, repurposed—and the once-distributed network collapsed into a single mnemonic silhouette. The plurality of the original system survived only as the idea of a singular lost tablet, a condensation of an entire administrative cosmology into one imagined object.

The twentieth-century multiplication of Emerald Tablets therefore marks a reversal of that mnemonic compression. Modern esoteric writers—unaware of the administrative logic they were unconsciously replicating—began producing texts that mirrored the distributed structure of the ancient decree network. In multiplying the tablet, they restored what history had erased: a world in which cosmic authority was never contained in a single stone, but dispersed across a coordinated grid of inscriptions.

Seen from this vantage, the proliferation of Emerald Tablets in Theosophy, occultism, and New Age Hermeticism does not signal a degeneration of the myth. It signals a reactivation of its original architecture. The myth, after centuries of enforced singularity, expands again into its primal multiplicity. The many modern tablets—however historically inaccurate—recreate the deeper truth that the ancient system was plural from its inception.

The multiplication is thus not a mistake, nor an inflation born of modern imagination. It is the myth returning to its source.

The Emerald Tablet Was Once Real — Just Not How We Imagined

The medieval Sufis did not invent the Emerald Tablet; they inherited a memory so thoroughly mythologized that its administrative, theological, and cosmological foundations had already dissolved into symbolic haze. What they received was the afterimage of a once‑elaborate Egyptian–Persian–Greek apparatus of inscriptional governance—a political technology designed not merely to communicate but to structure reality. By the time this memory reached the Arabic Hermeticists of the 8th–9th centuries, it had already passed through centuries of reinterpretation, condensation, and ritual forgetting. Yet beneath the mythic sediment, the outline of its origin remains discernible: the trilingual decree tablets of Ptolemaic Egypt.

These stelae were never ornamental curiosities. They were cosmic‑administrative engines, engineered to fuse divine sanction, civic regulation, and imperial law into a single material surface. Their tripartite construction—hieroglyphic for the gods and eternity, demotic for the Egyptian populace, Greek for the Hellenistic bureaucracy—encoded a universe in which metaphysics and government were not separate domains but mutually reinforcing layers of the same epistemic architecture. Distributed across the nomes in a grid that would echo centuries later in the territorial logic of the diocese, these stelae operated as the infrastructure of Egyptian sovereignty, the substrate on which the state rendered the cosmos legible and binding.

When the Ptolemaic regime collapsed and successive ideological orders—Roman, Christian, Islamic—rose to overwrite its cosmology, this inscriptional infrastructure became untenable. Objects that had once synchronized heaven and administration could not be allowed to remain intact under a rival theological dispensation. Their destruction was not an accident of time but a deliberate act of political and metaphysical sanitation. Some were smashed to sever their cosmic charge; some were buried to nullify their authority without desecrating them; others were cannibalized into buildings where their inscriptions would be silenced even as their stones endured. A few were entombed intact, safeguarded precisely because their potency was too dangerous to obliterate.

What survived was not the tablets themselves but the cultural memory of their disappearance. In this vacuum, myth rushed to fill the space left by obliterated materiality. The memory of a distributed system of cosmic‑legal inscriptions collapsed into the silhouette of a single indestructible tablet, a relic imagined to have resisted the erosions of history. This transformation followed a familiar ancient logic: when a world‑ordering object is destroyed, it becomes legendary, transmuted into a symbol of the very order that once grounded it.

Thus the Emerald Tablet of medieval Hermeticism is not a foreign intrusion into history, nor an alchemical fantasia torn from Atlantis. It is the compressed residue of the world’s first truly multilingual cosmic decree—a genre of inscription born in Ptolemaic Egypt, refracted through the symbolic vocabulary of Arabic esotericism, glimpsed again through the accidental survival of the Rosetta Stone, and ultimately reconfigured by the metaphysical ambitions of modern occultism. Each stage in this transmission reshaped the memory of the object while preserving its essential function: to serve as a surface upon which cosmic truth and political order could be articulated as one.

What survives today is legend, but legend anchored in a material genealogy. Behind the Hermetic myth stands the trilingual law‑tablet, the last surviving conceptual link to a vanished system in which writing, rulership, and cosmology were fused into a single epistemic instrument. These stelae are the true ancestors of the Emerald Tablet of Hermes—the historical substrate upon which centuries of esoteric interpretation built not fantasy, but a transfigured memory of real power.

Leave a comment