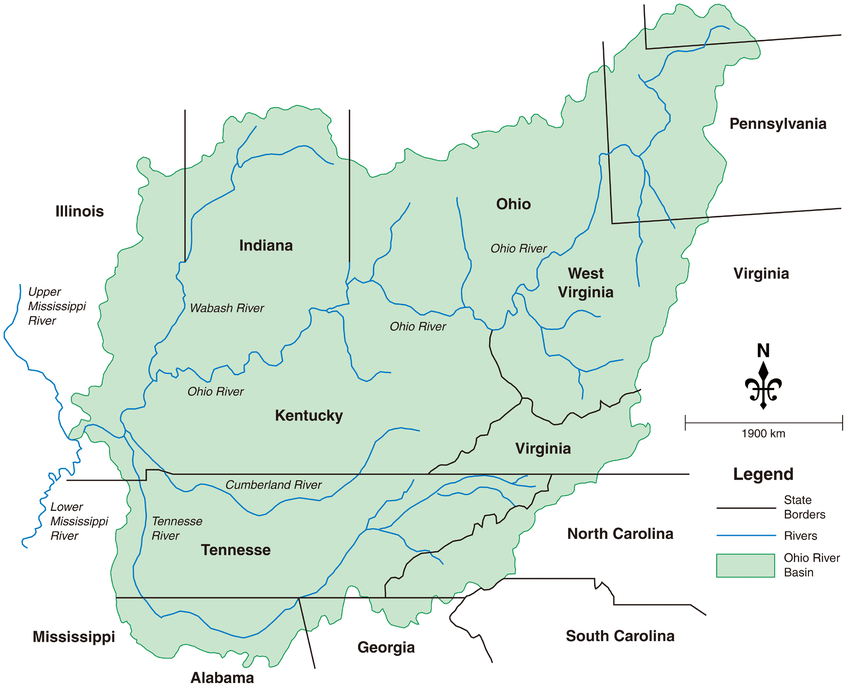

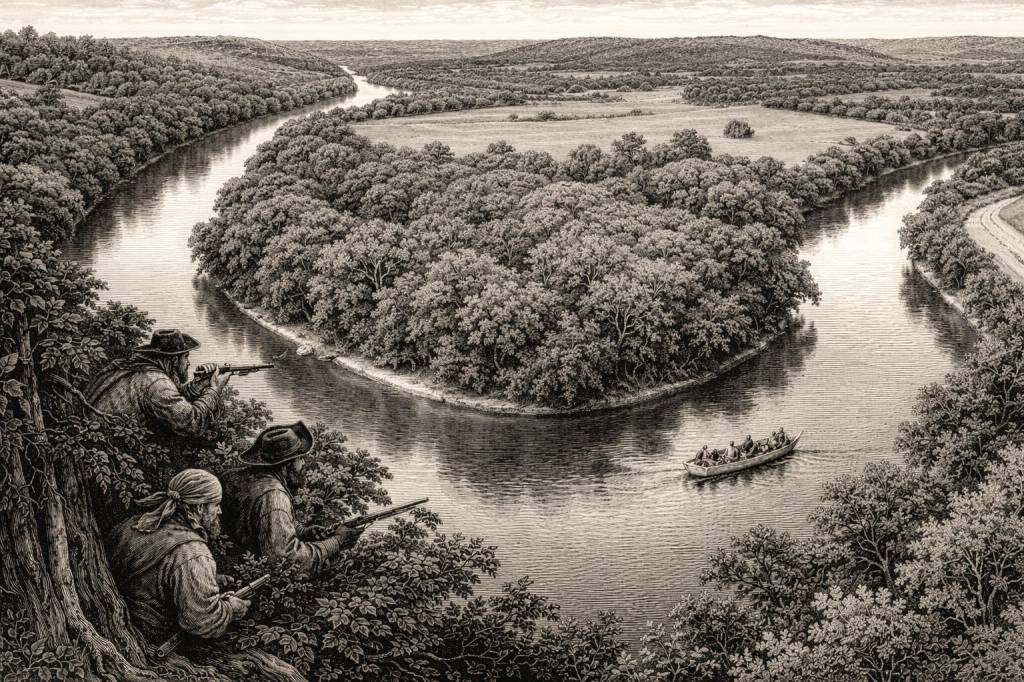

Before Chicago had an Outfit, before New York had families, and long before organized crime acquired Italian surnames, the American frontier already supported something far more fluid—and arguably more powerful: river‑based criminal syndicates moving quietly along the Ohio, Wabash, and Mississippi corridors. These were not loose bands of thieves. They were integrated systems that fused counterfeiting, land seizure, intelligence gathering, transportation monopolies, and political influence into what amounted to parallel governments embedded directly inside early American expansion. Rivers were not scenery. They were infrastructure. Whoever controlled them controlled trade, migration, and information.

These frontier syndicates did not announce themselves with flags or formal charters. They emerged quietly at ferry crossings, trading posts, river bends, and county courthouses. A tavern keeper might double as an informant. A ferryman might decide which cargo moved first—and which never arrived. Local sheriffs could be partners rather than obstacles. What looks, at a distance, like scattered outlaw activity begins, up close, to resemble coordination: shared intelligence, pooled capital, reciprocal protection, and disciplined retaliation. The frontier did not lack order. It generated its own.

Out of that environment—where geography rewarded consolidation and weak federal oversight invited private enforcement—one figure gradually comes into focus: James Ford.

Ford died in 1833, but during his lifetime he did more than lead a gang. He consolidated territory. He embedded loyalists in civic positions. He leveraged ferry rights and river access into leverage over movement itself. What he built may have been the first truly organized criminal empire in the interior United States—not a roaming band, but a structured frontier syndicate with revenue streams, informants, enforcement crews, and political insulation. His enterprise demonstrates how these corridor networks functioned: territorial control paired with covert finance and calibrated violence. Later formations—the Sturdivants, Quantrill’s raiders, and ultimately the James–Younger gang—appear less as spontaneous eruptions of outlaw culture and more as inheritors of a working model. Ford was not an aberration. He was an early architect of the system.

James Ford: Frontier Political Boss, River Pirate, Proto–Mob Leader

James Ford was not a drifter outlaw. He operated in plain sight as a wealthy landowner and respectable businessman, while simultaneously functioning as a political operator who controlled Ford’s Ferry Territory on the Ohio River and—covertly—directed a sophisticated criminal organization. This dual identity was not accidental. It was the mechanism. Legitimacy on paper provided cover for extraction in practice.

Ford’s enterprise touched nearly every frontier revenue stream that mattered: counterfeiting, horse theft, slave running, murder‑for‑hire, river piracy, armed robbery, the strategic use of explosives, systematic corruption of officials, and intelligence gathering on wealthy travelers and merchants. But to understand why his operation could scale before the Civil War, you have to see the industrial layer beneath the outlaw layer.

This is pre‑war America when “industry” doesn’t necessarily mean smokestacks—it means resource chokepoints. Salt is a perfect example. In the early nineteenth century, salt is not a seasoning; it’s preservation, storage, and survival. It keeps meat edible, it stabilizes food supplies, and it functions like a frontier commodity standard. Whoever has access to saltworks controls a strategic node in the regional economy. In southern Illinois this centered on the Saline Creek / Illinois Salines near present‑day Equality—federally supported salt works that supplied much of the lower Ohio Valley. Nearby stood the later‑notorious Crenshaw House, operated by John Hart Crenshaw, long associated with kidnapping rings and forced transport south. This was not peripheral geography; it was the industrial heart of the corridor Ford moved inside. Ford’s public legitimacy wasn’t built only on land and ferry rights—he had stakes in salt production and the labor contracts that fed it. Saltworks required large workforces, steady hauling routes, and reliable protection—exactly the same logistical needs as ferries, holding sites, and river transfer points. Control of salines meant control of wagons, guards, contracts, and downstream distribution. That necessity creates an ideal cover story for armed men moving along roads, for “security” that looks like governance, and for a private economy that can hide contraband inside legitimate freight.

That same industrial reality intersects with the darkest “service market” of the era: slave catching—with Crenshaw’s operation at the Illinois salines illustrating how quickly ‘recovery’ slid into organized abduction. On paper, slave catching could be framed as a bounty system—private men hired to recover “property” under state law and social permission structures. In practice, that job description created a license for predation. A man with connections, boats, and armed crews could do more than return fugitives—he could transform “recovery” into kidnapping, and kidnapping into trafficking.

This is where Ford’s “pillar of the community” mask becomes operational rather than incidental. On the surface, he can appear as a respected businessman—ferry operator, landholder, militia man, salt investor—someone providing stability in a violent corridor. But in the same borderland environment, a respectable title can also serve as camouflage for the Reverse Underground Railroad dynamic: networks that abducted free Black people and forced them into slavery in the Deep South. While historians debate the degree of Ford’s direct involvement in kidnapping operations, the structural overlap between ferry control, salines labor, and reverse-rail networks is difficult to ignore.

What matters for the system logic is this: once a ferry boss has a road, a ferry, a place to hold people, and a way to move them south under cover of “law,” the difference between slave catching as a “service” and human trafficking as an enterprise becomes a matter of scale and intent. Ford’s organization didn’t just exploit the frontier’s weak institutions. It learned how to wear them—how to look like commerce while operating as extraction, how to look like law while running a corridor.

This was not chaos. It was organized extraction.

Modern estimates suggest Ford commanded an influence network of 300 to possibly over 1,000 people at its peak—an extraordinary number for frontier America. That scale reframes him entirely. Ford was not a local thug. He was the operator of a regional syndicate.

Crucially, his territory intersected with one of the most infamous logistics nodes of the era: Cave‑in‑Rock on the Ohio River. Long before Ford consolidated his ferry domain, Cave‑in‑Rock functioned as a pirate harbor and criminal entrepôt—a natural limestone fortress where river brigands staged ambushes, cached stolen goods, forged alliances, and disappeared into caverns carved directly into the bluff. Its geography mattered: steep walls, hidden chambers, and immediate river access made it an ideal coordination hub for operations running both east–west and north–south. Ford’s rise should be understood as the institutional successor to that earlier pirate ecology—less theatrical, more disciplined, but built on the same spatial logic. Cave‑in‑Rock taught the corridor gangs that whoever mastered terrain could privatize transit itself.

Just upriver and inland, sites like Potts Inn entered regional legend as liminal waystations where travelers slept, horses were changed, rumors traded hands, and sometimes people simply failed to reappear. Potts Inn occupies a strange place in frontier memory: half hospitality stop, half whispered cautionary tale. Inns, ferries, and taverns were not passive services. They were intelligence nodes. A room ledger doubled as a target list. A meal purchase signaled liquidity. A casual conversation revealed routes, cargo, and companions. Ford’s organization exploited this architecture, embedding informants and allies inside the everyday infrastructure of movement.

The Ohio River Valley and Wabash River Valley were the highways of early America. Whoever controlled those waterways controlled trade between Appalachia, Illinois, Missouri, and the Mississippi system. Ford understood this. His gang effectively taxed movement—extracting value from anyone who passed through their corridors.

Seen this way, Ford belongs in the same lineage as the later Sturdivant gang, the Missouri–Kentucky border raiders, Quantrill’s irregulars, and ultimately the James–Younger network. These were not isolated criminals. They were successor systems, inheriting a working model: territorial control paired with covert finance, calibrated violence, and embedded political protection.

Ford’s organization is best understood as a proto‑state—a shadow government that managed transit, enforced its own laws, minted its own money, and treated the river economy as a privatized domain.

Counterfeiting as Infrastructure

What distinguishes Ford’s era from later gangster mythology is the centrality of counterfeiting—not as a side hustle, but as foundational infrastructure.

In pre–Civil War America, currency was radically fragmented: private bank notes of wildly varying credibility, state issues, foreign coins, barter systems, and later Union greenbacks all circulated simultaneously. There was no unified standard and little reliable oversight. Trust was local. Verification was slow. This monetary fog created a perfect operating environment. Counterfeiting wasn’t merely fraud—it was liquidity. It was how payroll moved when banks were days away by river or horse. It was how bribes were funded when hard specie was scarce. It was how operations scaled quietly, without drawing the attention that large transfers of legitimate capital would have triggered.

A mature counterfeiting network functioned like a shadow treasury. It supplied payroll, bribe money, operational capital, forged documents, identity papers, land deeds, letters of transit, and safe‑pass credentials. Engraving itself was a guild craft, passed from master to apprentice, guarded through lineage and reputation. Plates were not just tools—they were sovereignty. They functioned like imperial seals. Whoever controlled them could manufacture legitimacy on demand, create purchasing power from nothing, and stabilize an underground labor force without touching formal banks.

Once you plug that capability into a river syndicate, the result is something far more sophisticated than outlaw crime: a mobile shadow economy. Labor could be paid in counterfeit notes while real proceeds were extracted from merchants, travelers, land deals, and downstream fencing operations. Risk was offloaded onto victims. Profit accumulated upstream. Cave‑in‑Rock provided concealment and staging. Inns like Potts supplied intelligence and target acquisition. Ferries created chokepoints. Counterfeiting provided the fuel that kept the entire machine running.

Ford’s network overlapped directly with later Midwestern counterfeiting corridors running through Cincinnati, St. Louis, and eventually Chicago—cities that doubled as engraving centers, redistribution hubs, and laundering markets. The Sturdivants operated inside this same ecosystem. So did later engravers trained in the Ohio Valley tradition, many tied to Cincinnati and St. Louis workshops. These were not isolated print shops. They were distributed mints embedded inside criminal logistics routes, coordinated through couriers, river pilots, and innkeepers who understood both currency flow and human movement.

Seen at scale, this system explains why master engravers became strategic assets and why kidnapping, coercion, and ransom entered the operational toolkit. This is the environment that eventually produces the Lincoln tomb plot—not as a bizarre one‑off crime, but as the logical endpoint of a culture where bodies became leverage, plates became crowns, and monetary authority itself was contested terrain.

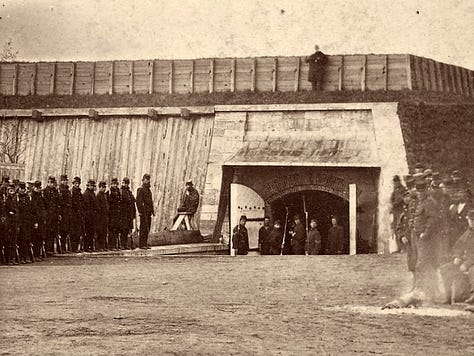

Lincoln vs the River Syndicates

By the time Abraham Lincoln enters national power, he inherits a country already divided between competing corridor economies—not merely political factions, but rival logistical systems with incompatible futures.

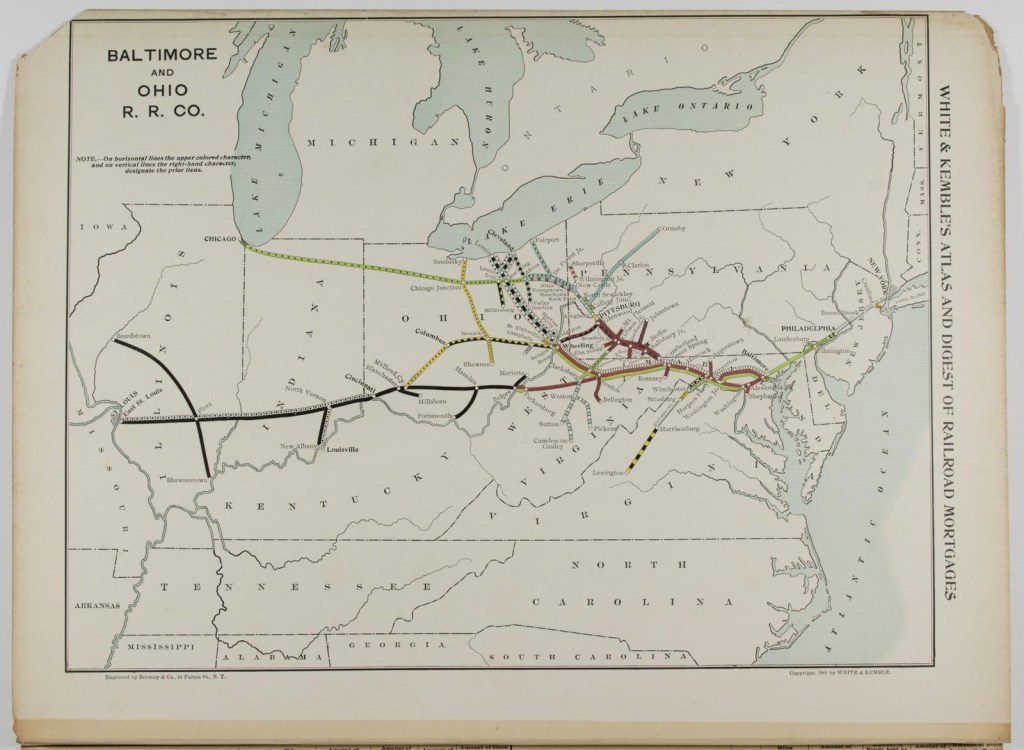

On one side sit river cartels, canal monopolies, barter‑heavy Appalachian trade loops, and frontier syndicates like Ford’s: decentralized, cash‑light, relationship‑driven networks that thrive on ambiguity, regional loyalty, and fragmented currency. On the other rises an entirely different vision of America—rail standardization, centralized banking, federal currency, telegraph lines, and nationally integrated infrastructure. Lincoln’s administration pushes hard toward central banking and unified rail networks, not as abstract modernization projects but as weapons of consolidation. This agenda directly threatens canal pirates, counterfeiters, and river mafias whose power depends on local sovereignty, slow communication, and monetary chaos.

In practical terms, Lincoln is attempting to collapse dozens of semi‑autonomous economic zones into a single national machine. That means replacing ferries with rail depots, barter with banknotes, engraved plates with Treasury seals, and corridor bosses with federal authority. Every mile of track laid undermines a river chokepoint. Every standardized dollar weakens a counterfeiting guild. Every telegraph line shortens the operational window of syndicate intelligence networks. What looks like infrastructure policy from Washington reads, on the frontier, as hostile takeover.

Illinois and Missouri become critical hinge states in this struggle. The traditional “gateway west” did not always run through Chicago; earlier commercial gravity flowed through St. Louis, southern Illinois, and the Ohio River basin. Nauvoo, the Mormon city, was larger than Chicago in its early years, operating as a disciplined economic bloc with its own militia, courts, and trade relationships. The Ohio–Wabash–Mississippi triangle formed a parallel America—river‑first, relationship‑based, and only loosely accountable to federal power. Ford dominated portions of that system. Lincoln was attempting to dismantle it.

Seen this way, Lincoln is not merely preserving the Union. He is forcing a regime change in how America moves goods, money, and authority—and the river syndicates know it.

Mormons, Militias, and the Vacuum

Early Mormon communities functioned as quasi‑sovereign blocs—disciplined, economically integrated, and internally governed through their own courts, militias, cooperative labor systems, and trade networks. They pooled resources, coordinated settlement, defended territory, and moved as a unified body across frontier space. To neighboring power structures—particularly the Ford river mafia along the Ohio corridor and the expanding Illinois counterfeiting rings tied to Cincinnati and St. Louis—this represented something unprecedented: a vertically integrated society operating outside conventional patronage chains and outside syndicate control.

The 1838 Missouri Extermination Order violently fractures this arrangement—but its impact does not stop at the state line. Issued by Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs, it becomes a political precursor for what follows in Illinois, where accommodation, containment, and eventual removal unfold through militia pressure, legal ambiguity, and administrative drift rather than explicit executive decree. By the time Thomas Ford rises to the Illinois governorship a few years later, the template is already in place: the Mormons are treated less as full citizens and more as a destabilizing population to be managed.

During Ford’s administration, escalating local violence, militia mobilizations, and political paralysis culminate in the killing of Joseph Smith and the unraveling of Nauvoo—events that occur not by formal extermination order, but on Ford’s watch, inside his state, amid fractured authority. Property is seized, communities collapse, and populations ultimately move westward—first through executive violence in Missouri, then through accumulated coercion and breakdown of protection in Illinois.

What disappears is not merely a religious group, but a functioning regional stabilizer—one that had provided labor discipline, territorial coherence, and economic continuity across large stretches of Illinois and Missouri. Their removal leaves behind abandoned land claims, broken supply routes, unguarded river crossings, and politically orphaned towns—precisely the kind of logistical gaps river syndicates and counterfeit networks were built to exploit. In other words, the Ford governorship does not engineer the collapse—but it presides over it, as frontier coercion migrates from overt executive force to local militias, civic breakdown, and administrative surrender.

Into that vacuum flows a different kind of order. Militia culture expands. Border violence normalizes. Quantrill’s raiders, James–Younger networks, Ford‑aligned river crews, and Illinois counterfeiting operations inherit territory once held by organized settlement. The Danites morph from internal Mormon security into roaming enforcement culture. Missouri border gangs professionalize. Confederate irregulars later absorb these same recruitment pools. What follows is not random lawlessness—it is organizational succession, as Ford’s corridor model and the counterfeit economy extend deeper into former Mormon space. A disciplined communal economy collapses, and extraction networks rush in to occupy its logistical footprint.

This is not coincidence. It is systemic collapse followed by criminal inheritance: settlement corridors become raid corridors, cooperative labor becomes forced tribute, and civic authority is replaced by armed patronage operating inside the same river‑and‑engraver ecosystem that Ford helped pioneer.

From James Ford to Jesse James

James Ford dies in 1833, but his model survives him—because the geography shifts while the logic remains. In the decades that follow, we see a second wave of “outlaw Fords” emerge through the Jesse James / James–Younger orbit—most notably Robert Ford and his brother Charles Ford—not as blood relatives of the river boss, but as structural descendants of Ford’s corridor system. River control becomes rail control. Intelligence on wealthy targets scales from flatboats to Pullman cars. Covert violence moves from isolated ferry crossings to scheduled train timetables. Counterfeit finance evolves alongside expanding western banks and mobile payroll shipments. What popular memory treats as roaming banditry is better understood as organized crime adapting to new infrastructure: coordinated crews, political safe harbor, intelligence on payroll movements, and selective high‑value strikes—Ford’s operating system, rebuilt on steel.

As the frontier pushes westward, crime reorganizes around new gateways. St. Louis functions as the hinge between river America and the overland frontier—a clearinghouse of freight, currency, migrants, and rumor. The Ozarks, Hot Springs, and later resort and rail towns like Branson become liminal zones: part spa culture, part gambling haven, part criminal retreat. These are not random outlaw hideouts; they are logistics rest stops within a widening extraction corridor. Wealth moves through them—mining money, cattle money, railroad money, land speculation money—and syndicates follow liquidity.

Where Ford mastered choke points on the Ohio, postwar gangs master choke points on steel. Railroads compress distance and concentrate value. Instead of ambushing isolated river craft, western gangs intercept scheduled trains carrying payroll, gold shipments, bond transfers, and insured freight. The target profile changes: no longer scattered merchants, but corporate treasuries and federally backed assets. The scale increases. The violence professionalizes.

The James–Younger gang inherits this framework after the Civil War. Quantrill provides the militarization—irregular warfare tactics refined in border conflict. Missouri–Kentucky border culture supplies recruits hardened by guerrilla experience. What emerges in the West is not spontaneous banditry but Ford’s corridor model adapted to rail: territorial intelligence, political sympathy networks, mobile safe havens in places like the Ozarks, and selective high‑yield robbery rather than random theft.

This is how frontier syndicates evolve into postwar outlaw culture—not romantic bandits on horseback, but organized extraction networks adjusting to a new transportation regime. The technology changes. The operating system does not.

Ford, Theater, and Name Recursion

Here historical irony deepens.

Completely unrelated by documentation, yet symbolically resonant, the Ford name resurfaces decades later in Washington through the Ford brothers who operated Ford’s Theatre: John T. Ford, James R. Ford, and Henry (“Harry”) Clay Ford—a legitimate theatrical enterprise rooted in Baltimore’s theatre world and extended into the capital’s performance circuit. John was the principal operator and expansionist, the one who took a former church on Tenth Street and rebuilt it into a modern venue in 1863. But the operation was emphatically a family machine: James functioned as the treasurer and business manager, the man whose job was receipts, payroll, and ledgers; Henry served as the house manager, handling the building, the staff, and the nightly mechanics of the show.

That specificity matters because the assassination doesn’t happen in an abstract “theatre.” It happens inside a working family operation with adjacent back‑channels and support spaces. The complex included the Star Saloon building next door—its lower floors commercial, its upper levels converted into lounges and sleeping rooms used by the Ford brothers in connection with the theatre. On April 14, 1865, Henry is literally in the box office counting receipts when the shot cracks the air. Within days, all three brothers are arrested and held while the War Department tears the theatre apart for evidence, and the building is effectively taken out of their hands for years. The Fords are eventually cleared, but the stain—and the seizure—hardens into a kind of bureaucratic curse. The Ford name, in other words, is not only present at Lincoln’s death; it is entangled in the machinery of suspicion and confiscation that follows.

But the recursion matters narratively: Ford appears both at the origin of river crime and at the site of Lincoln’s assassination. And it doesn’t stop there.

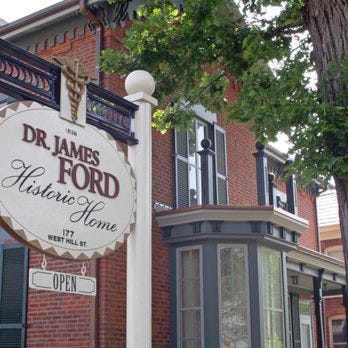

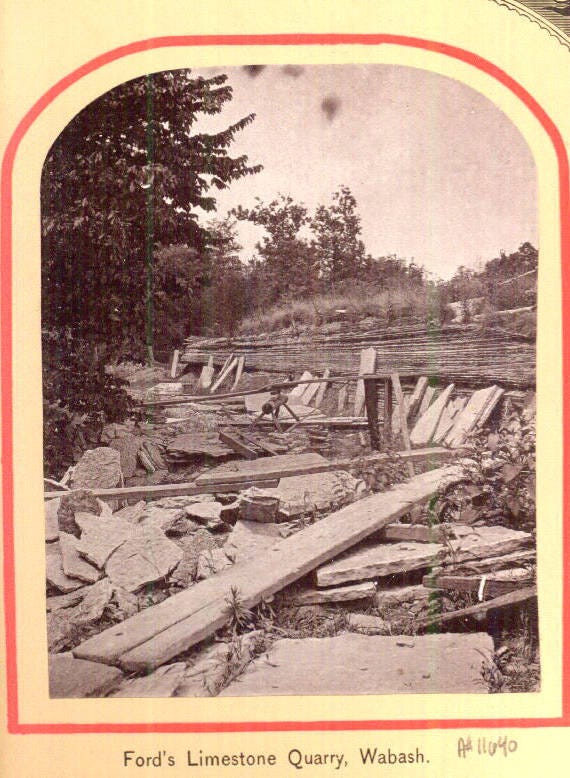

In Indiana, another unrelated James Ford name resurfaces again—this time not in entertainment or river coercion but in the language of measurement, metallurgy, and infrastructure. In Wabash, a nineteenth‑century physician named Dr. James Ford builds an 1840s home and surgery center that still stands as a historic site. He serves as a Civil War surgeon and becomes a local pillar—doctor, amateur architect, agronomist, and civic builder. His son, Edwin Ford, later designs a practical device that quietly shapes modern water systems: the first Ford meter box, built in a basement workshop, with a patent filed in late 1898 and a company born from that invention.

But the meter box is not just a clever enclosure. It sits at the center of a broader industrial shift. Ford Meter Box grows into a brass works operation—manufacturing fittings, couplings, valves, and service saddles that regulate how water enters, leaves, and is measured within municipal systems. Brass—an alloy of copper and zinc—is not ornamental here; it is functional sovereignty. Brass resists corrosion. It threads cleanly. It seals under pressure. It becomes the invisible architecture beneath streets and buildings. Control the fittings and you control flow.

Copper, too, is not incidental. The broader Midwest and Great Lakes region had been tied to copper trade for centuries—Indigenous extraction networks around Lake Superior long predated industrial mining. By the nineteenth century, Michigan’s copper boom and regional distribution networks fed factories across Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and beyond. Copper becomes the nervous system of modernity—conducting water, conducting heat, conducting electricity. Brass works translate raw metal into interface points where pressure is regulated, volume measured, and liability assigned. Meter boxes become the literal accounting devices of infrastructure.

What makes the name recursion feel almost engineered is that, in Wabash, “Ford” isn’t folklore—it’s civic architecture. Honeywell Arts literally preserves the Dr. James Ford Historic Home, a restored mid‑19th‑century physician’s house and surgery center that frames Ford as a Union Army surgeon and community pillar. And just a few blocks away sits the Honeywell Center’s 1,500‑seat Ford Theater, added during the Center’s 1994 expansion—Ford as marquee, not menace, a name attached to culture and public gathering rather than extraction. Put that beside the industrial Ford: Edwin H. Ford’s meter‑box invention and the company born from it—patent filed in 1898, later incorporated in Wabash in 1911—turning the family name into a century‑plus water‑infrastructure machine. So the arc tightens: the frontier “Ford” suggests shadow corridors and coercive tolls, while the Wabash “Ford” suggests measured flow, civic philanthropy, and public trust. In the same region, a name can be both pirate legend and respectable ledger—proof that American power and influence doesn’t always change names despite no familial bond.

The symbolic shift is striking: where earlier corridor syndicates manipulated counterfeit plates to control currency, industrial successors manufacture precision metal fittings to control utilities. Measurement replaces forgery. Standardization replaces fragmentation. Instead of engraving sovereign seals, factories stamp threads calibrated to municipal specification.

This logic extends into control systems more broadly. Companies like Honeywell, founded in the Upper Midwest and later headquartered in Minneapolis, build thermostats, regulators, aerospace controls, and industrial monitoring devices—technologies designed to manage temperature, airflow, fuel mixtures, and eventually avionics. The humble Honeywell thermostat becomes one of the most widely deployed industrial artifacts of the twentieth century, spreading into millions of homes, schools, offices, and factories—standardizing indoor climate the same way rail once standardized distance. That diffusion required vast logistics: regional distributors, wholesalers, installers, service networks, and replacement parts pipelines moving through the same freight corridors that once carried salt, counterfeit plates, and payroll shipments.

Honeywell’s rise parallels the maturation of American infrastructure: from river transport to rail, from rail to factory, from factory to automated control. And the parallel with Wabash is striking. At the same time Ford Meter Box is shipping water meters and brass fittings around the world—devices that literally measure and gate municipal flow—Honeywell is shipping thermostats and regulators that measure and gate heat and energy. Two massive companies, both emerging from small Midwestern towns, both dependent on global distribution channels, both quietly embedding accounting devices into everyday life. The through‑line is regulation—of heat, of pressure, of movement, of capital.

By the time we arrive at Henry Ford, the terrain has shifted again but the structural pattern persists. Detroit rises on the ruins of Fort Detroit—the French post founded in 1701 by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, later absorbed into a succession of British and American fortifications. After the War of 1812, the U.S. builds a new star fort on the Detroit River; by 1849 it is formally named Fort Wayne in honor of General Anthony Wayne. In practice, these forts are not just military symbols. They are logistics anchors—interfaces between waterways, roads, depots, payroll, and the industrial shoreline.

That quartermaster logic spreads across the region during the Civil War. The Midwest becomes a supply basin: wagons, harness leather, iron hardware, barrels, uniforms, horses, fodder, and replacement parts moving through river landings and rail junctions. The Ohio River Valley functions as a conveyor belt feeding inland nodes toward Chicago and the Great Lakes, while cities like Detroit, Fort Wayne, South Bend, and Indianapolis become manufacturing and staging zones where procurement, repair, and distribution start to look like permanent industry rather than temporary war work. In that environment, firms like Studebaker—a wagon maker turned war supplier—learn how to scale standardization, contract manufacturing, and national distribution. Early auto manufacturers inherit that same template: the wagon is replaced by the car, but the supply chain mentality remains. Brass flows from municipal fittings into radiators and engine components. Copper winds into ignition systems and wiring harnesses. Rail becomes factory; factory becomes automobile; automobile becomes a national mobility grid.

Henry Ford does not invent the system. He inherits and scales it. He industrializes corridor logic into a repeatable machine: automobiles stamped like currency, assembly lines replacing engraving benches, financing models replacing counterfeit payroll, dealership networks becoming territorial nodes tied to oil supply chains and federal highways. But the syndicate thread doesn’t vanish just because production becomes legal. It mutates into labor governance.

As unions rise, Ford becomes famously hostile to organized labor. His company’s Service Department—run by Harry Bennett—functions as an internal security apparatus: surveillance, intimidation, strikebreaking, and discipline carried out with the methods of a private police force. The violence becomes public in episodes like the 1932 Ford Hunger March and the 1937 Battle of the Overpass, where union organizers are beaten while cameras roll. At the same time, Ford’s public politics harden into nativist ideology, including antisemitic publishing through the Dearborn Independent and the dissemination of The International Jew.

Across this arc you can see the continuity you’ve been tracing: corridor control becomes factory control; counterfeit authority becomes managerial authority; armed crews become corporate security; the frontier syndicate becomes the industrial empire. The names change, the uniforms change, the technologies change—but the underlying logic persists: control the corridor, control the measurement, control the flow.

From Rivers to Rail to Factories

James Ford’s syndicate was not a historical anomaly. It was an early prototype of American organized power, a working demonstration of how transportation control, counterfeit finance, intelligence networks, political cover, and industrial succession could be fused into a single operating system. Long before the language of racketeering statutes or federal agencies existed, these corridor networks had already solved the problem of governance without government: they regulated movement, monetized uncertainty, and enforced compliance through private violence or logistical control.

Out of this world emerge both the Secret Service and the modern logistics state—not as opposites, but as institutional responses to the same frontier condition. The federal government does not invent centralized control in a vacuum; it builds it in reaction to men like Ford, to counterfeit economies, to shadow treasuries, to river syndicates that proved how profitable decentralized power could be.

And Lincoln stands at the hinge, attempting to consolidate a nation while corridor syndicates resist. His rail policies, currency reforms, and infrastructure push are not abstract modernization projects. They are counter‑insurgency against an older American system that moved through ferries, inns, salines, engravers, and armed crews.

James Ford was more than just a criminal. He was a systems engineer of the frontier underworld. His river empire prefigured Chicago’s mob. His counterfeiting model prefigured federal monetary control. His intelligence networks prefigured modern organized crime. He shows us that American power did not arrive fully formed in Washington—it was field‑tested along rivers, perfected in borderlands, and only later formalized into agencies, banks, and factories.

He represents the forgotten layer of American history: the moment when rivers were kingdoms, engravers were kings, mobility was monetized, and legitimacy itself was a contested technology. What follows—railroads, automobiles, control systems, federal oversight—is not a break from that world. It is its continuation by other means. It rose from choke points, from measurement, from movement—and from men like Ford who taught the system how to organize itself. And the name itself lingers across that corridor like a repeating signal: Ford the river boss, Ford the theater operator, Ford the industrialist—unrelated by blood, yet braided through the same logistical spine—until it finally surfaces in the White House with Gerald Ford. Not a single dynasty, but a distributed one, where a surname becomes a brand stamped across piracy, performance, plumbing, production, and power.

Leave a comment