The Frontier Was Never Empty

The American frontier was never just land and rifles. It was institutional experimentation in real time — a rolling laboratory where authority had to be invented on the fly.

Before railroads stitched the continent together and before federal power could meaningfully project itself westward, legitimacy traveled person‑to‑person. It moved through lodges, churches, fraternal halls, revival tents, treasure‑hunting expeditions, and the circuits of itinerant preachers who crossed territories faster than any bureaucrat ever could. The early American West was not secular. It was saturated with micro‑priesthoods.

Organizations like the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF), Masonic lodges, early Protestant circuits, and frontier congregations did far more than preach salvation. They quietly built the scaffolding of society. They organized burial insurance and cemeteries when no municipal systems existed. They pooled money and credit, effectively acting as proto‑banks. They shared coded trust through handshakes, oaths, and ritual recognition. They distributed charity, managed widows and orphans, and regulated behavior long before county offices or welfare departments appeared. They controlled information flow, deciding who was trustworthy, who was suspect, and who belonged.

In a land with weak state presence, lodge plus church became infrastructure.

Protestantism in this era functioned less like modern denominational religion and more like a localized jurisdictional system — a moral racket in the neutral sense of the word. It provided parallel authority where formal law had not yet arrived. Congregations adjudicated disputes. Ministers mediated conflicts. Lodges enforced reputation. Fraternal societies created portable identity. If you wanted protection, credit, burial, or legitimacy on the frontier, you didn’t go to Washington. You went to your lodge, your pastor, or your brotherhood.

Before federal administration matured, these networks effectively acted as intelligence webs. They tracked newcomers. They passed rumors. They identified talent. They filtered danger. They created early warning systems across hundreds of miles of wilderness. Power did not travel on paper — it traveled on relationships.

This is the part modern history often misses: the frontier wasn’t anarchic. It was hyper‑organized, just not by the state. It was governed by overlapping religious, fraternal, and communal systems that blended faith, finance, identity, and surveillance into something remarkably efficient.

And once you see that, everything that follows — Mormonism, communal experiments, jungle empires, lost cities, priesthood migrations — starts to look less like coincidence and more like pattern.

Proto-Priesthood Movements

Mormonism did not emerge in a vacuum. It arrived in the middle of a crowded spiritual marketplace, during a century that treated America like an open laboratory for new priesthoods.

The nineteenth century produced wave after wave of competing sacred experiments. Swedenborgians mapped heaven like engineers. Gnostic‑leaning Christian mystics searched for hidden wisdom inside scripture. Adventists recalculated the apocalypse on pocket calendars. Spiritualists tried to speak directly with the dead. Perfectionist movements promised moral purification through communal discipline. And scattered across the frontier were dozens of small sects attempting to build self‑contained worlds with their own rules, rituals, and internal hierarchies.

The Oneida Community matters here more than most, because it shows just how far these experiments were willing to go. Oneida wasn’t merely religious — it was social engineering. It explored communal marriage, sexual regulation, controlled reproduction, treasure‑hunter cosmology, and the idea of a closed religious society that could redesign human behavior from the inside out. They weren’t dabbling in symbolism. They were trying to rewrite the operating system of daily life.

Across the frontier, similar projects kept appearing in different guises. These were proto‑OTO‑style experiments, not in the later European occult sense, but in the deeper structural sense: small elites claiming moral authority to reorganize society. Who slept with whom. Who reproduced. Who owned property. Who held power. Who spoke for God.

The harem question surfaced repeatedly. So did the communal wife question. So did the controlled breeding question. These weren’t fringe fantasies whispered in back rooms. They were serious debates inside American utopian movements that believed civilization itself was up for renegotiation.

This is the part that reframes Mormonism.

Mormonism did not invent this energy. It inherited it.

Where other movements fractured under excess, Mormonism consolidated. Where others experimented endlessly, Mormonism standardized. Where many communities burned out on ideology, Mormonism built administration. It took the raw frontier impulse toward sacred authority and did something radically different with it: it stabilized it, formalized it, and made it portable.

Lodge + Church = Portable Empire

The critical innovation of Mormonism was structural, and this is where it separates itself from every other frontier experiment. It didn’t just preach or speculate or improvise — it engineered a complete social system that could move.

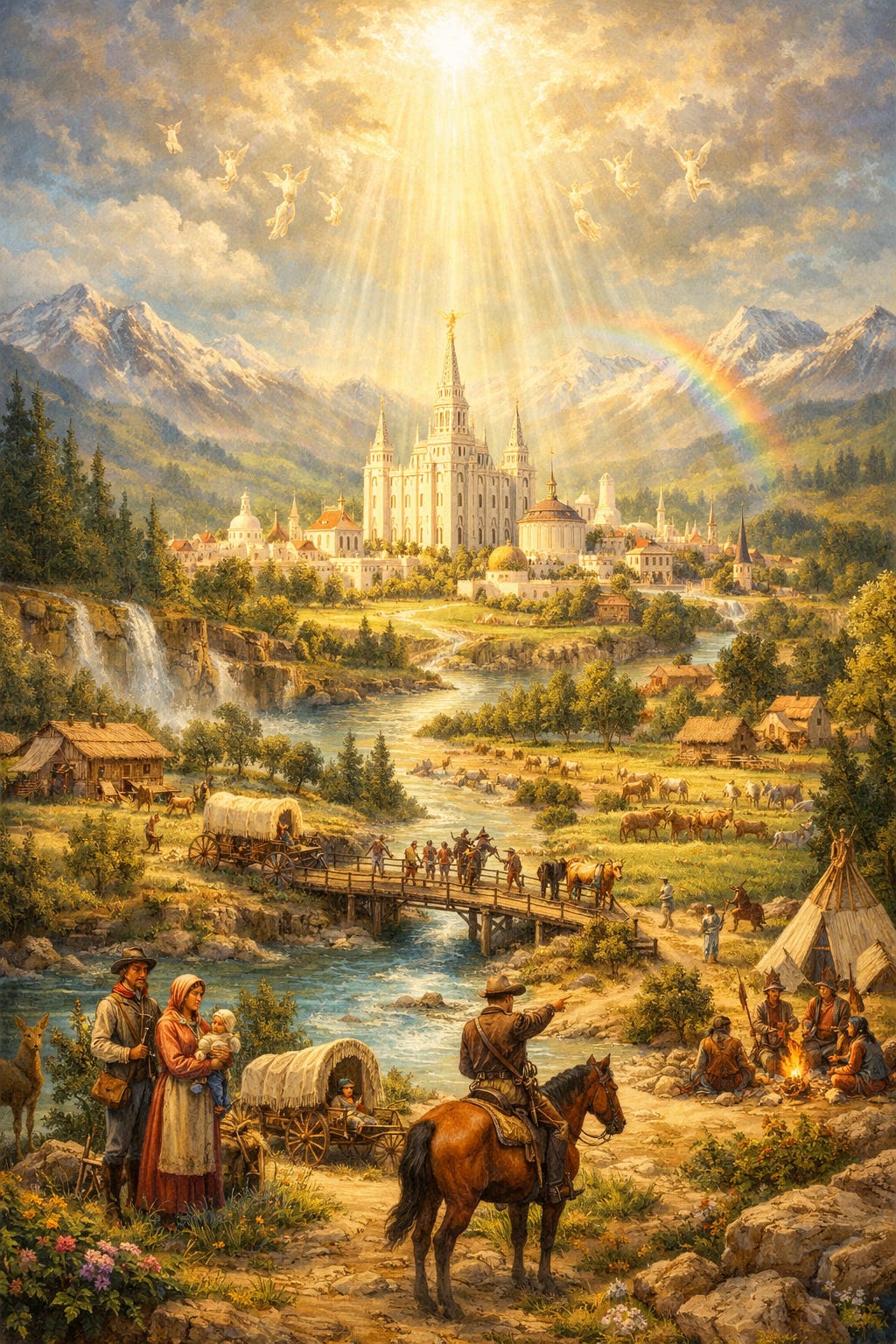

It quietly fused lodge secrecy with priesthood hierarchy, ritual drama with covenant genealogy, territorial ambition with communal welfare. Handshakes met ordinances. Oaths met family trees. Temple symbolism merged with migration logistics. Then the whole apparatus picked up and headed west.

At that point Mormonism stopped behaving like a religion in the modern sense and started behaving like something closer to a portable civilization. It functioned as an intelligence network first, a cult second, and only later a society in the conventional sense. Information traveled faster than wagons. Reputation moved faster than mail. Authority followed priesthood lines rather than county borders.

Long before Utah became a state, it was already operating as an organized territorial system. Supply chains were coordinated across thousands of miles. Records were obsessively kept — births, deaths, marriages, property, lineage. Internal courts handled disputes. Internal militias provided security. Entire populations migrated on schedule, in formation, with leadership hierarchies already in place.

Nothing about this was accidental. While other frontier movements burned out on ideology or collapsed under their own excesses, Mormonism standardized itself. It replaced improvisation with procedure. It traded charisma for administration. It turned revelation into bureaucracy.

What emerged wasn’t merely a church — it was frontier governance disguised as religion, a priesthood-powered operating system capable of building towns, managing economies, disciplining communities, and reproducing itself across vast empty spaces.

Zion, New Jerusalem, and the Frontier Prophet Archetype

Joseph Smith. Brigham Young. Even figures like Charles Manson much later. The names change, the eras shift, but the frontier keeps generating the same archetype: the prophet who claims authority where institutions are thin, who draws a circle on a map and calls it sacred, who gathers followers into isolated communities and governs them through charisma wrapped in cosmology. These figures don’t appear because America is uniquely irrational — they appear because frontiers collapse distance faster than they build institutions, leaving space for personality to become law.

America, over and over, produces these moments of prophetic gravity. Land becomes covenant. Geography turns theological. A valley, a desert basin, a mountain corridor — suddenly it’s not just territory, it’s destiny. This is where the New Jerusalem / Zion motif takes root. The frontier stops being real estate and starts being a promise. Maps become scripture. Migration becomes liturgy. Settlement becomes sacrament.

But this pattern doesn’t originate in America. What looks uniquely American is actually part of a much older European tension playing itself out on a larger, emptier stage. On one side sits the Holy Roman Empire model: inward, territorial, institutional, obsessed with borders, titles, archives, and administrative continuity. Authority lives in buildings, seals, courts, and paperwork. On the other side is the Iberian mystic current: Atlantic-facing, plus ultra, outward-looking, chasing sanctified space beyond the horizon. Authority lives in motion — in voyages, conversions, frontier parishes, and the belief that holiness can be relocated.

Before Napoleon shattered Europe’s balance, the HRE tried to preserve sacred order by consolidating power inside the continent. Iberia went looking for it across oceans. One system defended the center. The other hunted the edge.

So when frontier prophets start declaring Zion in Missouri, or building theocratic cities in Utah, or carving communes out of wilderness, they aren’t inventing something new. They’re reenacting an ancient split in Western civilization — the choice between guarding holiness at the center or chasing it to the edge of the world. America simply gave that drama more room to run, more land to absorb it, and fewer walls to stop it.

Mexico: Indigenous Empire in Catholic Clothing

When Mexico declares empire under Agustín I (1822), it is not reviving Rome, and it is not resurrecting medieval Christendom. It is attempting something far stranger and far more fragile: wrapping an Indigenous imperial memory in Catholic ceremony and hoping the synthesis will hold.

What emerges is a kind of ceremonial palimpsest. The old Aztec capital logic is quietly re-coded into a European throne. Indigenous hierarchies are absorbed into creole military command. Catholic ritual is layered over older concepts of sovereignty that predate Spain entirely. Processions replace temples. Bishops stand where priest-kings once stood. The empire speaks Latin prayers while standing on Nahua foundations.

It is, in essence, a native empire wearing European garments.

And for a moment, it almost works. The symbolism is powerful. The Church provides moral gravity. The army provides force. The people recognize the vertical shape of authority, even if the language has changed.

But the structure underneath is hollow.

Mexico’s empire collapses quickly not because the idea is weak, but because the administration is thin. There is no deep bureaucratic spine. No inherited civil service. No durable institutional memory capable of translating ritual legitimacy into day-to-day governance. Authority lives in spectacle rather than systems. Loyalty flows through personalities instead of procedures.

Agustín’s empire is a ceremonial crown placed atop a society that has not yet learned how to reproduce imperial order mechanically. It is theology without logistics, sovereignty without archives, priesthood without paperwork. The symbolism outruns the infrastructure.

Where Brazil will later succeed by building administration first and mythology second, Mexico tries the reverse — and pays the price. The result is not restoration but rupture: a brief imperial flare followed by fragmentation.

Brazil: The Jungle Empire

Brazil is different, because Brazil does not merely inherit empire — it receives it whole.

Portugal’s Templar lineage, carried forward through the Order of Christ, does not dissolve with the medieval world. It migrates seaward, embedded in maritime bureaucracy, sacred kingship, and mercantile logistics. When Napoleon fractures Europe, the Portuguese court does something unprecedented: it evacuates across the Atlantic. The monarchy does not flee into exile — it relocates sovereignty.

Empire physically moves into the rainforest.

Rio de Janeiro becomes a functioning imperial capital. Ministries, archives, treasuries, naval command, and court ritual are transplanted intact. Brazil is no longer a colony orbiting Lisbon. Lisbon is now orbiting Brazil. A European empire reboots itself inside the largest jungle on Earth.

Brazil becomes court center and administrative node, a maritime empire reconstituted as a jungle empire — a distributed fortress disguised as wilderness. Roads, ports, plantations, and river corridors quietly replace crusader commanderies and cathedral cities. Authority is no longer anchored in stone capitals but in mobile bureaucracy and extractive networks.

Later, under Pedro I, accusations surface of a hidden inner circle — the Apostolado — a sacral-political cabinet operating outside formal channels. Whether exaggerated or not, the pattern is familiar. It mirrors earlier Iberian mystical currents like Los Alumbrados, not genealogically but structurally: inner illumination, chosen elites, authority flowing through proximity rather than law, spiritual intimacy substituting for transparent governance. This is Iberian mysticism translated into imperial administration.

Pedro I rules like a charismatic revolutionary prince and burns fast. Pedro II absorbs the lesson. He governs as priest-administrator rather than messianic monarch, trading spectacle for systems, mystique for paperwork, lineage for institutions. He builds schools, archives, observatories, railways, and census mechanisms. He professionalizes the state. Brazil stabilizes not through divine theater, but through bureaucratic gravity.

This is the critical distinction. Where Mexico attempts empire through symbolism and collapses, Brazil survives by operationalizing sovereignty. It becomes a post-European imperial continuity zone — a relocated court culture embedded in tropical geography, running on ritual memory but sustained by administration. A rainforest empire held together not by crowns alone, but by clerks, priests, engineers, and ledgers.

Brazil doesn’t imitate Europe. It absorbs it.

Zarahemla, Cumorah, and Manuscript 512

Before Mormon missionaries ever set foot in Brazil, the interior of South America is already thick with imperial afterimages. Manuscript 512 circulates in Portuguese archives describing a ruined stone city hidden in the jungle, complete with arches, inscriptions, and paved streets — not folk rumor, but an official colonial document quietly acknowledging something massive had once existed beyond the river lines. Bandeirantes push inland chasing gold and indigenous labor, leaving behind trails of rumor, broken missions, and half‑mapped river routes that read more like treasure charts than geography. Hy‑Brasil — the phantom Atlantic island — lingers in European cartography as a mirage of western paradise, a standing symbol of lands that are supposed to be there even when they can’t be reached. The rainforest becomes a projection surface for everything Europe lost: empire, sanctity, forgotten capitals, and displaced sovereignty. The English world later picks up this same thread through Percy Fawcett and the obsessive hunt for the “Lost City of Z,” treating the Amazon like a submerged Rome waiting to be rediscovered.

At the same time, Mormon sacred geography is being articulated in North America — Zarahemla, Cumorah, covenant civilizations wiped out by divine judgment. These are not borrowed coordinates. They’re parallel myth architectures emerging from the same Atlantic subconscious. The resonance is psychological, not evidentiary. Long before Joseph Smith, the Western imagination had already been seeded with Western Paradise, Hidden Empire, sacred ruins, and vanished priest‑kings waiting beyond the tree line. Jungle cities and promised lands were already embedded in civilizational memory, passed down through maps, sermons, travelogues, and speculative histories.

Mormonism doesn’t invent this longing. It slots into it.

The Book of Mormon arrives into a world already primed for lost hemispheric kingdoms, already haunted by rumors of American antiquity, already conditioned to believe that ancient authority might survive in wilderness corridors beyond imperial reach. What looks like religious novelty is actually convergence — frontier scripture meeting jungle myth, covenant theology intersecting imperial nostalgia. South America had been carrying the idea of buried empires for centuries. Mormon cosmology doesn’t create that idea; it formalizes it, baptizes it, and gives it administrative teeth. It turns diffuse imperial memory into priesthood narrative, converting geographic longing into covenant history.

Brazil as Economic Zion

Brazil is not Mormon Zion doctrinally. But structurally, it functions as something just as powerful: a post‑imperial refuge, a commodity powerhouse, an administratively coherent territory, a genealogically layered society, and a sacramentally literate culture already trained to think in terms of hierarchy, ritual obligation, and inherited authority. Where empire collapses elsewhere, priesthood order survives here — not as spectacle, but as habit.

Mormonism thrives in Brazil not because of secret Templar bloodlines or occult transmission, but because the ground is already prepared. Brazilians are culturally fluent in vertical authority. Catholicism has spent centuries teaching sacramental grammar. Extended family networks mirror covenant structures. Record‑keeping, lineage, and communal obligation feel familiar rather than alien. Conversion doesn’t require abandoning hierarchy — it simply reroutes it.

Brazil becomes a kind of economic Zion outside the old European system, not through prophecy but through compatibility. It offers scale, labor, stability, and spiritual literacy at the same time. It provides exactly what a portable priesthood civilization needs in the modern era: population density without secular hostility, tradition without feudal rigidity, and order without nostalgia. This is where post‑imperial energy goes when crowns fail but covenant logic still works.

The Philippines: Pacific Mirror

The Philippines mirrors Brazil for the same structural reasons: an Iberian Catholic foundation layered with American geopolitical management, commodity corridors tied into global supply chains, and top‑down urban rationalization under Daniel Burnham that translates empire into sidewalks, boulevards, and civic grids. Burnham’s Manila plan isn’t just city design — it’s imperial architecture rendered municipal, a way of teaching sovereignty through zoning, traffic flow, and monument placement. Spanish sacramental culture prepares the population for hierarchical authority; American administration supplies the logistics. What emerges is a post‑colonial society already fluent in priesthood logic and procedural governance at the same time.

So when Mormonism arrives, it doesn’t feel foreign. It feels legible. It enters environments where ritual authority already makes sense, where extended families mirror covenant structures, and where American systems have been normalized through schools, infrastructure, and military presence. Growth follows the same pattern as Brazil — not because of hidden plots, but because the cultural grammar is already aligned with portable priesthood civilization.

This is what modern analysis keeps missing. These movements don’t spread randomly. They move along prepared corridors: former empires, sacramental cultures, administrative overlays, and populations trained to recognize vertical authority. Mormonism doesn’t conquer these spaces — it interfaces with them.

The Occult Intelligence Network of the Frontier

Across these systems, the pattern keeps reasserting itself with almost mechanical consistency — not as ideology, but as engineering. Weak frontier states invite lodge networks. Lodge networks mature into priesthood authority. Priesthood authority stabilizes populations. Stabilized populations attract capital. Capital carves corridors. Corridors generate myth. Myth binds people to place. Inner circles emerge to manage legitimacy. Secret cabinets appear to manage risk. Administration mutates to match whatever sacred language happens to be in circulation. This is not chaos. It is a repeatable, field-tested method for building durable power wherever formal sovereignty is thin or collapsing.

Empire does not vanish when flags come down. It migrates. It sheds uniforms and reappears as accounting systems. It trades fortresses for railways, banners for census rolls, crowns for registries, crusader armor for ledgers. It moves from Crusader commanderies to Portuguese maritime nodes, from maritime nodes to jungle courts, from jungle courts to frontier priesthoods, from frontier priesthoods to transnational covenant communities. The architecture changes, but the logic does not. Authority becomes quieter, more procedural, more embedded in everyday life.

The American frontier was not a vacuum. It was a pressure chamber — a place where old European systems were stripped down to their load-bearing beams and rebuilt in portable form. Titles became callings. Nobility became lineage. Canon law became church courts. Mercantile routes became wagon trails. Empire learned to travel light.

Brazil was not an accident. It was a relocation — a full imperial stack lifted out of Europe and replanted in tropical soil, complete with archives, priesthood grammar, extractive logistics, and administrative muscle.

Mormonism was not a random cult. It was a frontier priesthood solution — a scalable governance model disguised as revelation, capable of producing towns, economies, records, militias, and multigenerational loyalty on demand.

The Philippines were not peripheral. They were Pacific infrastructure — a civic laboratory for translating empire into grids, schools, ports, census forms, and sacramental compliance.

Lost cities are not archaeological proof. They are mythic memory — cultural afterimages of displaced sovereignty, echoes of unfinished empires searching for new ground.

The Atlantic world has always oscillated between institutional empire — the inward HRE model of archives, borders, and legal continuity — and mystical outward expansion, the Iberian plus ultra instinct to sanctify new horizons and relocate sacred authority beyond the edge of the known world. One guards continuity. The other pursues renewal.

America inherited both — and the frontier forced them to fuse into a mobile sovereignty system, carried by belief, enforced by administration, and reproduced through family, record, and ritual.