Medieval geography should not be understood as an objective description of the world. Maps functioned as controlled instruments of access—administrative technologies that regulated who was permitted to know specific places, routes, resources, and relationships, and under what conditions. They encoded jurisdiction as much as terrain. From this perspective, the repeated appearance of Hy‑Brasil on medieval charts, the drifting placement of Atlantic islands, and Iberia’s rapid consolidation of maritime power after 1500 are not products of confusion, fantasy, or cartographic incompetence. They reflect a structured process of knowledge custody, political rupture, selective leakage, and eventual recombination—the same dynamics visible whenever institutional control over infrastructure collapses and is later rebuilt.

This argues that Hy‑Brasil was neither a purely mythical island nor a simple mapping error, but a residual imprint of an Atlantic logistical system—a real network of routes, relay points, and resource access whose custodianship passed from Norse guild traditions into Templar management before fragmenting in the early fourteenth century. What followed was not an age of heroic discovery, but a period of damaged archives, displaced memory, and competing reconstructions. The so‑called Age of Exploration emerges here as an administrative recovery operation: crowns rebuilding access to systems that already existed, using partial maps, degraded intelligence, and repurposed guild knowledge to reassert control over Atlantic circulation.

The Norse Inheritance: Routes Without Maps

Long before medieval monarchies turned their attention toward the Atlantic, Norse mariners operated within an oral‑guild system of navigation. Rather than relying on abstract coordinates or fixed maps, their practice prioritized embodied knowledge of routes, prevailing winds, ocean currents, seasonal timing, and intermediate staging points. Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland functioned not as territorial colonies in an imperial framework, but as operational relays—distributed nodes within a wider maritime logistics network.

Leif Erikson’s westward voyage constitutes the earliest surviving written record of this much older system. The Norse did not “discover” western lands in the modern sense; they activated preexisting route knowledge inherited through generations of seafaring practice. Oral tradition and navigational reconstruction both indicate that the Scandinavian–Greenland corridor was designed around line‑of‑sight island hopping: from Norway through the Faroes and Iceland, then onward toward Greenland, sailors were rarely out of visual contact with land except for one limited open‑water stretch. This was not random exploration—it was a deliberately chained route architecture optimized for visibility, redundancy, and seasonal reliability.

Importantly, this knowledge was never centralized in royal or ecclesiastical archives. It circulated through guild memory, maintained through repetition, apprenticeship, and lived navigation rather than formal documentation. By the early modern period, fragments of this older Atlantic intelligence resurface in unexpected places. John Dee and Edward Kelley, working within Elizabethan occult–mathematical frameworks, spoke of northern lands and ancient western inheritances not as speculative fantasy but as recoverable domains tied to Britain’s imperial destiny. Dee’s writings frame north-western Atlantic as part of a lost jurisdictional field—an inheritance to be reclaimed rather than a frontier to be found. Newfoundland later enters English consciousness through this same damaged archive: not as a revelation, but as confirmation that earlier route systems had existed and could be reactivated.

Within this structure, Iceland appears not as a destination but as a relay node—a site for regrouping crews, exchanging navigational intelligence, and transferring materials onward through the system. This functional role becomes analytically significant later, when Iceland begins to absorb displaced geographic memory after institutional collapse, preserving fragments of Atlantic knowledge while losing the operational context that originally gave them meaning.

The Templars as Custodians of the Atlantic System

Between roughly 1100 and 1307, the Knights Templar functioned less as a religious fraternity than as a proto‑global infrastructure operator. Their authority did not derive from doctrine but from logistics. It rested on four tightly integrated capacities: financial clearing, military contracting, large‑scale construction, and custodianship of strategic corridors. They managed capital flows, personnel movement, and technical knowledge across jurisdictions, often superseding royal authority by controlling the mechanisms that made sovereignty operational.

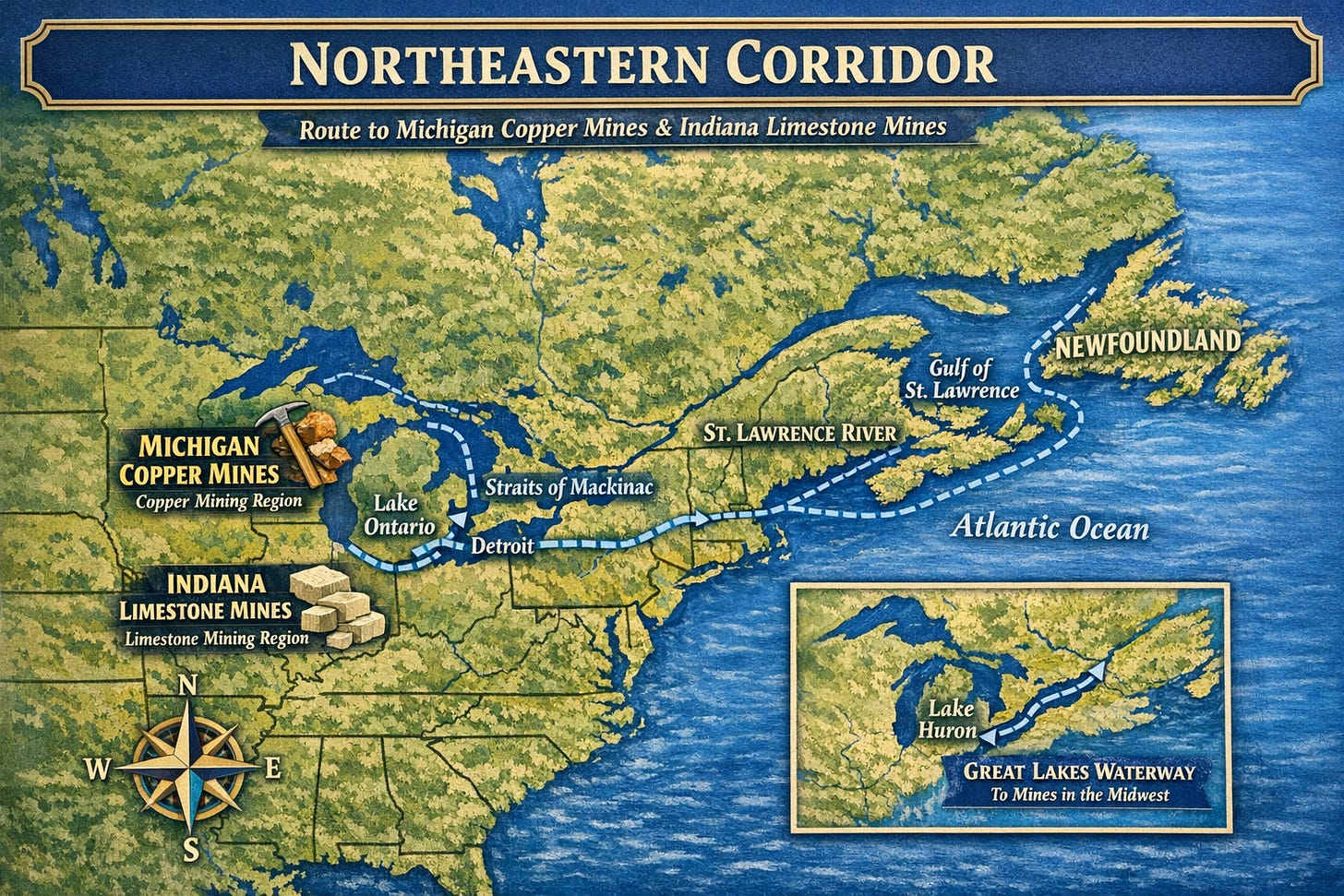

Through Scottish, Irish, Mediterranean, and Byzantine channels, the Templars inherited fragments of older Atlantic logistics—systems organized around resource access rather than settlement or population transfer. These pathways linked tin from Britain, copper associated with the Great Lakes region, and gold from the southern Atlantic sphere into a quiet material circuit. This was not colonial expansion in the modern sense. It was extractive routing: restricted corridors, compartmentalized knowledge, and deliberately low visibility. Power was exercised through access, not occupation.

Within this framework, Iceland likely persisted as a northern relay node. Its geographic isolation, weak centralized governance, and continuity of Norse maritime culture made it ideal for staging materials, transferring crews, and preserving navigational intelligence outside the reach of consolidating monarchies. Iceland offered something more valuable than territory: jurisdictional ambiguity. During the Templar period, the Atlantic system appears to have remained intact—not publicly legible, but structurally coherent, economically active, and intentionally silent.

The Rupture: 1307 as a System Collapse

The suppression of the Templars by the French crown was not driven by theology but by fiscal emergency and sovereign insecurity. Philip IV was effectively bankrupt, deeply indebted to the order, and increasingly threatened by an organization that controlled credit, construction labor, fortified sites, and transnational routing independent of royal authority. The arrests of 1307 functioned as a coordinated asset seizure: personnel were detained, properties expropriated, archives confiscated, and operational continuity forcibly terminated.

In modern terms, this was not the dissolution of a religious order—it was the takedown of a distributed infrastructure platform. A financial clearing network collapsed. A logistics lattice fractured. Intelligence pathways were severed. What had operated as a coherent system was abruptly reduced to disconnected components.

The dynamics closely resemble the collapse of a contemporary intelligence or supply-chain apparatus under hostile takeover: operators scatter, documentation fragments, technical knowledge becomes siloed, and no successor institution retains end‑to‑end visibility. The earlier Albigensian Crusade had already demonstrated the enforcement logic behind this move. Southern France served as a proving ground, showing that autonomous regions, alternative economic models, and parallel knowledge systems would be eliminated once they exceeded the tolerance of centralized power.

After 1307, Templar knowledge did not vanish—it atomized. Navigational practices, financial techniques, construction expertise, and routing intelligence dispersed into guilds, merchant families, maritime fraternities, and regional power blocs. What was lost was not capability, but integration. The Atlantic system survived only as fragments, stripped of its coordinating architecture, leaving later states to reconstruct it piecemeal from degraded remains.

Knowledge Migration: Scotland, Iberia, and the North Atlantic

After the collapse, surviving components of the Templar network migrated selectively into regions where centralized royal authority was fragmented, contested, or administratively porous. Scotland functioned as a protective refuge, buffered by political instability and geographic distance. Ireland preserved continuity through oral transmission, maritime fraternities, and craft guild lineages that could carry technical knowledge without written archives. Spain and Portugal absorbed navigational methods, shipbuilding practices, and routing intelligence into newly centralized state frameworks. France, by contrast, experienced systematic purge and consolidation: assets were nationalized, alternative networks dismantled, and residual autonomy brought under crown control.

England never achieved full custodianship of the Atlantic framework. Although Norman aristocratic networks inherited isolated elements of Templar infrastructure—fortifications, financial instruments, and maritime contacts—they lacked the integrated operational knowledge required to run the system end‑to‑end. England inherited components, not architecture. This structural deficit helps explain its later historical posture as a seeker rather than a steward: dispatching expeditions to locate routes that already existed elsewhere, operating from degraded maps rather than intact logistics memory.

Meanwhile, Iceland, Greenland, and eventually Nova Scotia cohered into a northern fallback route—a reduced but persistent continuation of the earlier Atlantic network. This was not an expansionary corridor but a preservation channel, optimized for discretion rather than scale. Its logic later surfaced historically as New France, advancing southward through river systems and portage corridors—St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, Mississippi—rather than asserting dominance directly across open ocean. Power here moved inland along existing transport ecologies, preserving the older logistical grammar long after southern empires formalized their maritime regimes.

The Cartographic Leak: Hy‑Brasil Appears

By the late fourteenth century, European cartography begins to exhibit systematic distortion. The Catalan Atlas and related Iberian charts introduce Brazil‑like islands west of Ireland. These entries do not represent new geographic discovery. They function as leaks—fragments of operational knowledge surfacing after institutional collapse, recorded without chain‑of‑custody and stripped of their original logistical meaning.

What appears on these maps is not imagination but residue. As southern Atlantic intelligence migrates northward through copied charts, merchant notebooks, and secondary compilations, concrete locations become displaced and terminology degrades. Place‑names detach from routes. Coordinates detach from supply logic. Iceland absorbs the cartographic echo of Brazil not because the two are geographically related, but because Iceland remains one of the last stable reference points inside the surviving northern navigation framework. It becomes a semantic dock: a safe place for orphaned data to attach.

Hy‑Brasil operates here as a memory container—an artifact of infrastructure collapse. It is real enough to persist across generations of mapmakers, yet abstract enough to conceal the extractive network it once indexed. This is what degraded logistics look like on parchment.

This unstable phase persists for roughly a century—the typical lifespan of unmanaged technical knowledge before it either decays into folklore or is forcibly recomposed inside a new administrative regime.

England Arrives Late: Cabot and the Damaged Archive

By the time England begins searching for Brazil through figures such as John Cabot, the crown is operating inside a severely degraded information environment. The original custodians of Atlantic logistics are gone, their institutions dismantled decades earlier. What remains are derivative charts, second‑hand reports, and symbolic place‑names detached from route logic, supply chains, and operational memory. England is not entering an open frontier—it is attempting to reverse‑engineer a system that has already been quietly recomposed under Iberian authority.

This dynamic explains why Cabot sails west in pursuit of Brazil while Spain and Portugal consolidate ports, shipping lanes, and resource corridors across the Atlantic basin. England’s constraint is not ambition or seamanship; it is institutional continuity. Without integrated archives, navigational lineage, or inherited routing intelligence, English exploration becomes an exercise in forensic reconstruction—assembling expeditions from residual data rather than executing a living logistical architecture.

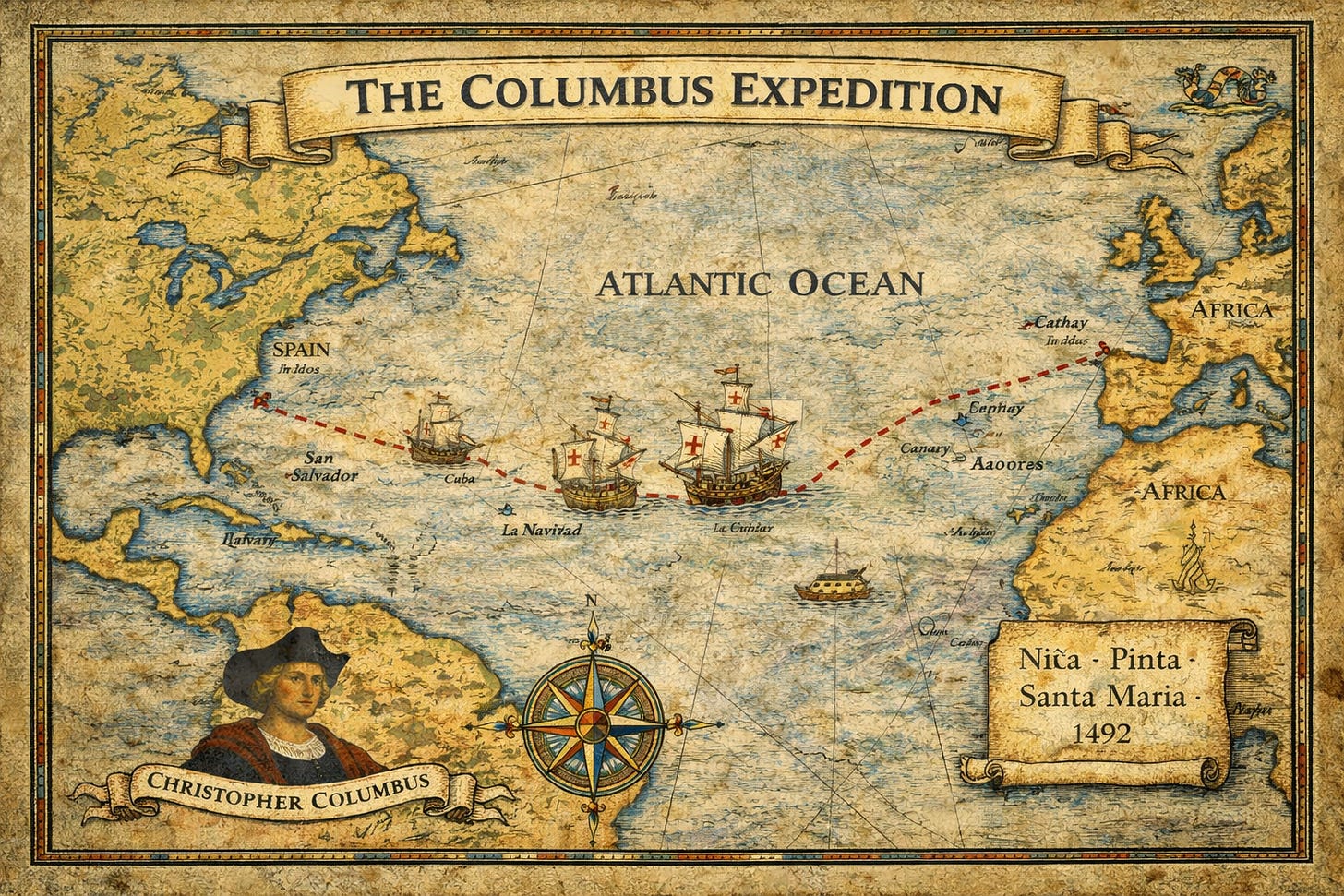

Iberian Recombination and the End of the Myth

Spain and Portugal do not inherit the Templar system as a finished structure—they reconstruct it under conditions of state consolidation and administrative centralization. Drawing on leaked cartography, standardized instruments (astrolabe, quadrant, later cross‑staff), and newly professionalized royal bureaucracies, they convert fragmented Atlantic intelligence into an integrated imperial operating system. What had once circulated through guild memory and informal routing becomes codified: maps are archived, pilots licensed, ports regulated, and access subordinated to crown authority. The Atlantic is no longer a distributed logistics field—it becomes a managed domain.

Columbus’s 1492 voyage should therefore be understood not as a moment of revelation but as a system restart under sovereign control. By 1500, Portugal establishes formal administrative presence in Brazil, transforming what had existed as dispersed routing knowledge into legally enclosed territory backed by taxation, charter, and military enforcement. Once Atlantic geography is absorbed into imperial recordkeeping, Hy‑Brasil loses its operational function. The cartographic placeholder collapses into legend. Iceland recedes to the margins. The northern relay network withers as southern maritime corridors—shorter, faster, and institutionally enforced—become dominant. What disappears here is not myth, but redundancy: informal access is replaced by centralized command.

Hy‑Brasil as a Shadow of Infrastructure

Hy‑Brasil should not be understood as a mythical island. It functioned as a cartographic residue—the trace of a real Atlantic logistics network whose institutional control fractured under political pressure. Iceland’s later association with Brazil reflects not geographic confusion but the displacement of operational knowledge after system collapse. What persisted was not a physical location, but a degraded memory of access.

From this perspective, medieval exploration appears less as heroic discovery and more as a process of knowledge management and recovery. Empires expand not primarily by encountering unknown worlds, but by inheriting—or reconstructing—routing systems and informational architectures that earlier institutions were forced to relinquish.

Hy‑Brasil did not vanish; it lost its administrative function.

Understanding this framework requires abandoning the assumption that pre‑modern societies lacked large‑scale logistical intelligence. The Atlantic system described here was not exploratory in character. It operated as infrastructure: coordinated movement of materials, personnel, and technical knowledge without centralized paperwork.

From the Bronze Age forward, Atlantic Europe depended on sustained long‑distance metal circulation. Tin from Cornwall and Brittany, copper from multiple continental sources, and later gold and silver were structural inputs into production systems, not luxury commodities. The trade corridors supporting these flows predated medieval states and persisted beyond them. What shifted over time was not the presence of these routes, but control over the expertise required to operate them.

The Norse did not originate this system. They inherited and refined one layer of it, introducing cold‑water navigation practices, seasonal sailing schedules, and northern relay points such as Iceland and Greenland. These locations were never intended as independent endpoints; they functioned as integrated components within a larger trans‑Atlantic chain.

Iceland’s historical role is best understood through logistics rather than permanent settlement. It produced little agricultural surplus and offered minimal value for imperial taxation, which is precisely what made it strategically useful. Iceland existed largely outside the administrative focus of major European crowns while remaining accessible, habitable, and operationally reliable.

Functionally, Iceland served three roles. As a relay, it allowed crews to rest, repair vessels, and resupply. As an archive, it preserved navigational knowledge through oral tradition and ritual practice, which proved more resilient than written records during periods of political purge. As a sink, it absorbed displaced geographic information when southern Atlantic knowledge became politically sensitive or dangerous to maintain openly.

This helps explain why Iceland remains culturally saturated with westward myth despite its later geopolitical marginality.

Scotland’s significance after 1307 derives from its political fragmentation and its position between Norse and continental systems. Rather than operating as a command center, Scotland functioned as a custodial refuge. Technical and logistical knowledge dispersed into building guilds, maritime fraternities, banking families, and oral custodial traditions instead of reconstituting as a centralized institutional order.

From Scotland, a reduced northern Atlantic route remained operational: Iceland to Greenland, Greenland to Nova Scotia, and onward into North America’s river networks. This pathway anticipates the later structure of New France, emphasizing inland circulation over direct oceanic control.

England’s delayed emergence as an Atlantic power reflects damaged institutional continuity rather than lack of ambition. Norman aristocratic influence did not confer custodianship of transnational logistical knowledge. England searched for Brazil because it no longer possessed intact archives of the earlier system.

Spain and Portugal advanced by recombining fragmented knowledge under centralized royal authority. Navigation practices were standardized, cartography institutionalized, and guild-based memory converted into state-managed archives. Once this consolidation occurred, Hy‑Brasil ceased to serve any operational purpose.

Columbus represents the administrative formalization of access rather than geographic discovery. After 1492, the Atlantic shifted from symbolic space to regulated territory. Portugal’s establishment in Brazil by 1500 marks the closure of the earlier concealment regime.

Gold in South America, copper in the Great Lakes region, and tin in Britain together form a coherent material circuit. These locations functioned primarily as resource nodes rather than settler colonies. Iberian powers did not discover these systems; they absorbed them into national administrative frameworks.

Hy‑Brasil and related legends persist as residual data—what remains when access is withdrawn and documentation fails. Myth survives where infrastructure once operated.

The Atlantic world was not discovered in the fifteenth century; it was reorganized. Hy‑Brasil marks the shadow of a logistical system whose custodianship fractured under political pressure. Its disappearance signals not error, but consolidation: secrecy rendered unnecessary by centralized power.