The continued appeal of the Tartaria idea should not be read as proof of a lost global empire erased by some hidden catastrophe. Instead, it reflects a real and well‑founded unease with the historical record itself: gaps in archives, sudden architectural discontinuities, and abrupt breaks in institutional memory that appear too systematic to be accidental. These irregularities are most visible in frontier regions—zones of trade, migration, and negotiation that were only intermittently governed and never fully stabilized under centralized state authority.

The mistake has not been the recognition that something is missing. That intuition is largely correct. The error lies in assuming that what disappeared must have taken the form most familiar to modern observers: a territorially bounded, monumental civilization with a capital, a bureaucracy, and a linear historical narrative. That assumption projects the logic of the nation‑state backward onto environments that operated according to very different rules.

What vanished was not a monumental empire, but a specific mode of organization: one optimized for mobility rather than permanence, coordination rather than sovereignty, and continuity through practice rather than through fixed institutions.

Frontier Space and the Problem of Historical Compression

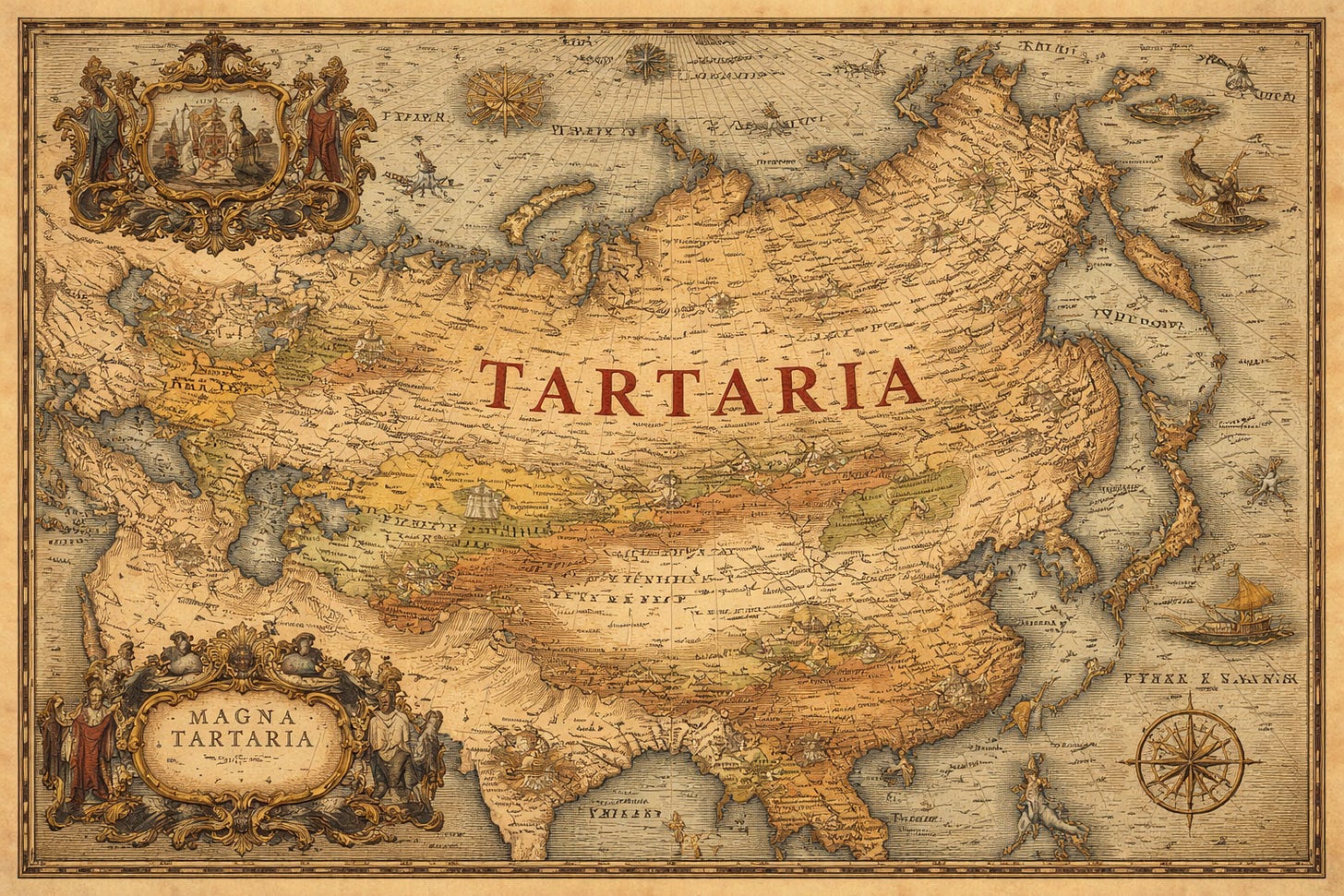

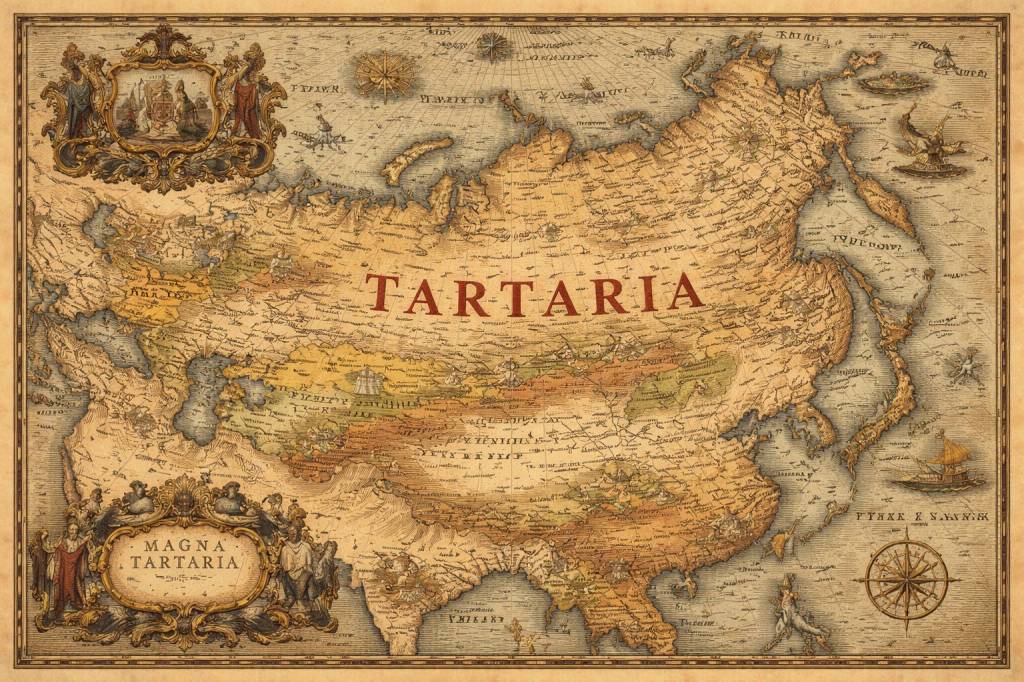

In early modern cartographic discourse, “Tartary” functioned less as a determinate political entity than as an epistemic category marking the limits of imperial legibility. The designation encompassed regions rendered intelligible through commerce, military contact, diplomatic exchange, and secondhand report, yet never fully subsumed within stable regimes of bureaucratic governance. Steppe ecologies, fluvial corridors, portage systems, and maritime littorals shared this structural condition: they supported dense populations, complex economies, and durable cultural norms while remaining inhospitable to sustained administrative enclosure.

As a consequence, these regions did not produce the archival architectures later privileged by territorial nation‑states. In place of centralized record‑keeping, they generated reproducible urban morphologies, provisional or modular building practices, guild‑mediated governance, oath‑based legal affiliation, and forms of law portable across jurisdictional boundaries. When modern observers encounter the fragmented traces of these arrangements—recurring settlement patterns dispersed across continents, classical facades that appear suddenly and disappear just as abruptly, or cartographic conventions that collapse vast territories under a single indeterminate label—they frequently infer the existence of a vanished empire. What is actually visible, however, is the residual material and representational imprint of frontier administration operating outside the documentary norms of later state formation.

The Confederation Model: Tribe as Function, Not Bloodline

A recurring analytical error in Tartaria-oriented narratives is the reification of “tribe” as an ethnic or genealogical unit, as though durable collective organization must necessarily be grounded in blood, ancestry, or shared origin myths. Historically, this assumption is untenable. Many of the most persistent and influential tribal formations were not kinship populations at all, but functional confederations: mobile, oath-regulated collectivities organized around trade, legal arbitration, specialized craft knowledge, and intermediary roles between competing imperial systems. Their durability derived not from lineage but from utility.

Such confederations included merchants, shipbuilders, translators, financiers, cartographers, convoy organizers, and frontier administrators—figures whose value lay precisely in their ability to move between jurisdictions without being fully absorbed by any one of them. Cohesion was maintained through shared legal regimes, ritualized trust mechanisms, standardized practices, and accumulated institutional memory rather than descent or territorial attachment. Membership was contingent and role-dependent, often reversible. Identity functioned positionally rather than genealogically, defined less by where one came from than by where one was authorized to operate at a given moment within circulating networks of exchange and obligation.

This organizational logic explains why certain symbols, settlement forms, architectural vocabularies, and administrative habits recur across vast geographic expanses without requiring a centralized sovereign authority or imperial command structure. It also explains why these groups are so poorly resolved within modern national historiographies. They did not operate as states, did not aspire to sovereignty, and did not leave archives calibrated to later bureaucratic norms. Instead, they functioned as interstitial systems occupying the negotiated spaces between states, where jurisdiction was fluid, authority was situational, and continuity was maintained through practice rather than territorial permanence.Scripture, Prophecy, and the Necessity of Memory

Mobile confederations face a chronic problem: dispersion. Without fixed territory, memory must be externalized. Oral tradition becomes codified law; ledgers become chronicles; origin stories become stabilizing myths.

Within this framework, the emergence of prophets and reformers is not anomalous or mystical. These figures function as system-reset narrators. Periodically, someone must restate who “we” are, clarify corrupted law, redraw moral boundaries, and re-unify scattered nodes of the network. This pattern appears repeatedly across history—in Biblical traditions, Islamic reform movements, rabbinic scholarship, and even in frontier religious movements of the modern era.

The power of these narratives lies not in their literal truth but in their capacity to preserve continuity across fragmentation. They are not evidence of secret global rule, but of institutional survival under conditions of mobility and pressure.

The Khazar Analogy and Its Limits

The Khazar polity is frequently invoked in polemical or conspiratorial registers, yet its analytical value is neither genealogical nor ideological but decisively structural. As a frontier formation situated astride major Eurasian trade corridors, Khazaria demonstrates how a multi-ethnic polity could deploy a portable legal–religious framework as a governing technology rather than as a civilizational claim. The adoption of such a framework functioned administratively: it standardized adjudication across diverse populations, stabilized commercial exchange, and reduced transaction costs in zones where imperial jurisdictions overlapped but rarely consolidated. In this sense, law operated as infrastructure. The move implied neither universal sovereignty nor concealed domination; it reflected a pragmatic response to mobility, pluralism, and the absence of enforceable territorial monopoly.

Read with methodological discipline, the Khazar case clarifies how legal systems optimized for portability, abstraction, and jurisdictional flexibility can serve as institutional scaffolding for frontier confederations operating outside fully territorialized state models. It illustrates authority exercised through procedure rather than territory, compliance secured through predictability rather than force, and continuity maintained through law rather than lineage. When wrenched from this structural context, however, the example predictably collapses into genetic essentialism or ideological myth-making. The distinction is not cosmetic. It is foundational: one mode of reading illuminates historically attested mechanisms of non-territorial governance, while the other forecloses analysis by substituting narrative fantasy for institutional form.

Iberian Syncretism and the New World Frontier

By the time Iberian powers entered the Atlantic world, they were not exporting a pristine Greco‑Roman inheritance or a uniformly Catholic institutional order. Late medieval Iberia itself functioned as a frontier society, shaped over centuries by layered legal, architectural, and mercantile syncretism produced through prolonged Christian, Jewish, and Islamic coexistence. Guild organization, construction techniques, contractual instruments, and commercial law routinely converged across confessional boundaries even where theological reconciliation remained impossible. What crossed the Atlantic, therefore, was not a coherent civilizational blueprint but a flexible frontier repertoire already conditioned by pluralism, legal hybridity, and jurisdictional overlap.

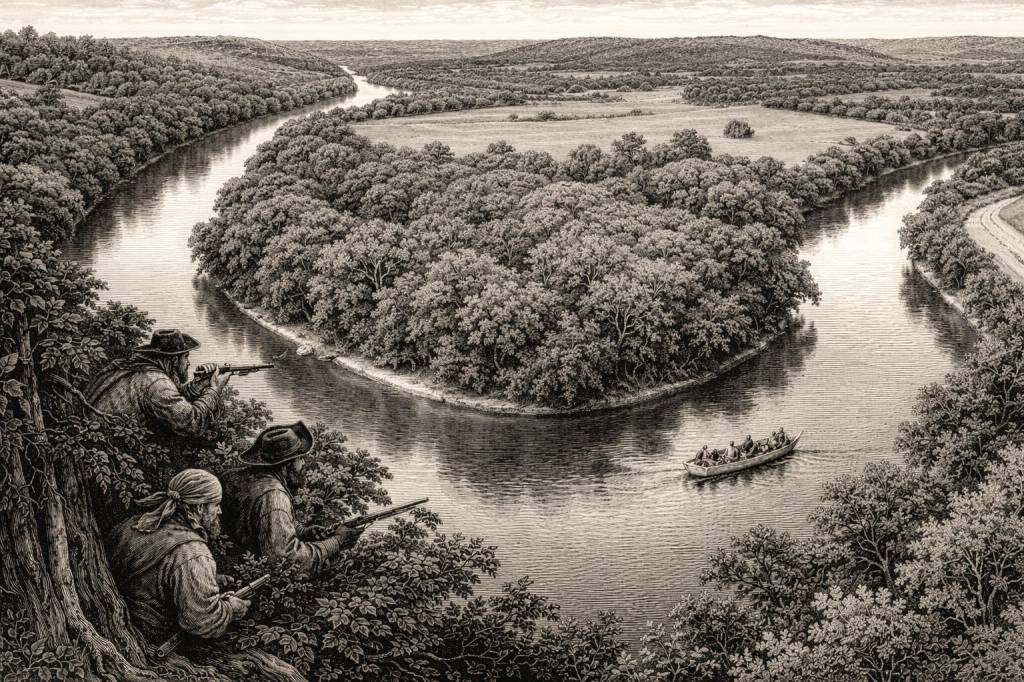

When Iberian expansion reached the Americas, it encountered dense indigenous trade networks and settlement systems organized around rivers, portage corridors, seasonal movement, and ecological constraint. The initial colonial landscape was not one of systematic replacement but of negotiated improvisation: hybrid town morphologies, provisional construction materials, and ad hoc institutional arrangements calibrated to local labor, climate, and logistics. Many early structures were deliberately temporary. Others were selectively repurposed, absorbed into churches, forts, or civic buildings, or dismantled as colonial authority stabilized and administrative rationality displaced frontier expedience.

Seen in this light, architectural and institutional discontinuities require no appeal to catastrophic erasure. Earlier frontier formations were overwritten not because they were ancient, forbidden, or deliberately suppressed, but because they were incompatible with emerging regimes of private property, cadastral mapping, public health regulation, taxation, and centralized governance. Their disappearance registers the imposition of bureaucratic legibility and territorial control, not historical annihilation. What was lost was not a civilization, but a mode of organization rendered obsolete by the consolidation of the colonial state.

The “White City” Problem and the Illusion of Lost Grandeur

Nineteenth-century exposition architecture offers a particularly instructive cautionary case for understanding the material logic behind the so‑called loss attributed to Tartaria. Urban environments that appear in surviving photographs as monumental marble cities—most famously the “White Cities” of world’s fairs—were, in fact, purpose-built spectacles constructed using deliberately impermanent techniques: plaster composites, timber framing, staff ornament, and theatrical facades engineered to simulate monumentality without committing resources to durability. These cities were designed to exist briefly, to coordinate labor, capital, and circulation for a finite interval, and then to vanish once their function had been fulfilled. Their dismantling was not concealment, nor failure, but completion.

This architectural logic mirrors frontier organizational systems more broadly. Across steppe, riverine, and portage-based environments, buildings were frequently conceived as infrastructural instruments rather than as monuments—temporary enclosures, halls, depots, and administrative shells optimized for mobility, seasonal use, and rapid reconfiguration. Such structures left light archaeological footprints by design. When authority shifted or circulation patterns changed, they were dismantled, repurposed, or simply abandoned, their materials recycled into subsequent builds. What later observers encounter, therefore, is not the aftermath of destruction but the residue of intentional impermanence.

Read in this context, Tartaria’s apparent architectural absence no longer requires catastrophic explanation. The “lost” mode was not stone-bound monumentality but a construction regime aligned with frontier governance: modular, provisional, and responsive to movement rather than permanence. As centralized states imposed cadastral mapping, property law, public health codes, and permanence-oriented urban planning, these impermanent forms were systematically replaced—and, crucially, rendered illegible within later historical narratives. The analytical error lies in mistaking buildings that were meant to disappear for evidence of a vanished ancient civilization, rather than recognizing them as artifacts of an organizational system whose success depended precisely on its ability to leave little behind.Tartaria as an Erased Mode of Organization

Nineteenth-century exposition architecture offers a particularly instructive cautionary case for understanding the material logic behind the so‑called loss attributed to Tartaria. Urban environments that appear in surviving photographs as monumental marble cities—most famously the “White Cities” of world’s fairs—were, in fact, purpose-built spectacles constructed using deliberately impermanent techniques: plaster composites, timber framing, staff ornament, and theatrical facades engineered to simulate monumentality without committing resources to durability. These cities were designed to exist briefly, to coordinate labor, capital, and circulation for a finite interval, and then to vanish once their function had been fulfilled. Their dismantling was not concealment, nor failure, but completion.

This architectural logic mirrors frontier organizational systems more broadly. Across steppe, riverine, and portage-based environments, buildings were frequently conceived as infrastructural instruments rather than as monuments—temporary enclosures, halls, depots, and administrative shells optimized for mobility, seasonal use, and rapid reconfiguration. Such structures left light archaeological footprints by design. When authority shifted or circulation patterns changed, they were dismantled, repurposed, or simply abandoned, their materials recycled into subsequent builds. What later observers encounter, therefore, is not the aftermath of destruction but the residue of intentional impermanence.

Read in this context, Tartaria’s apparent architectural absence no longer requires catastrophic explanation. The “lost” mode was not stone-bound monumentality but a construction regime aligned with frontier governance: modular, provisional, and responsive to movement rather than permanence. As centralized states imposed cadastral mapping, property law, public health codes, and permanence-oriented urban planning, these impermanent forms were systematically replaced—and, crucially, rendered illegible within later historical narratives. The analytical error lies in mistaking buildings that were meant to disappear for evidence of a vanished ancient civilization, rather than recognizing them as artifacts of an organizational system whose success depended precisely on its ability to leave little behind.

Tartaria as an Erased Mode of Organization

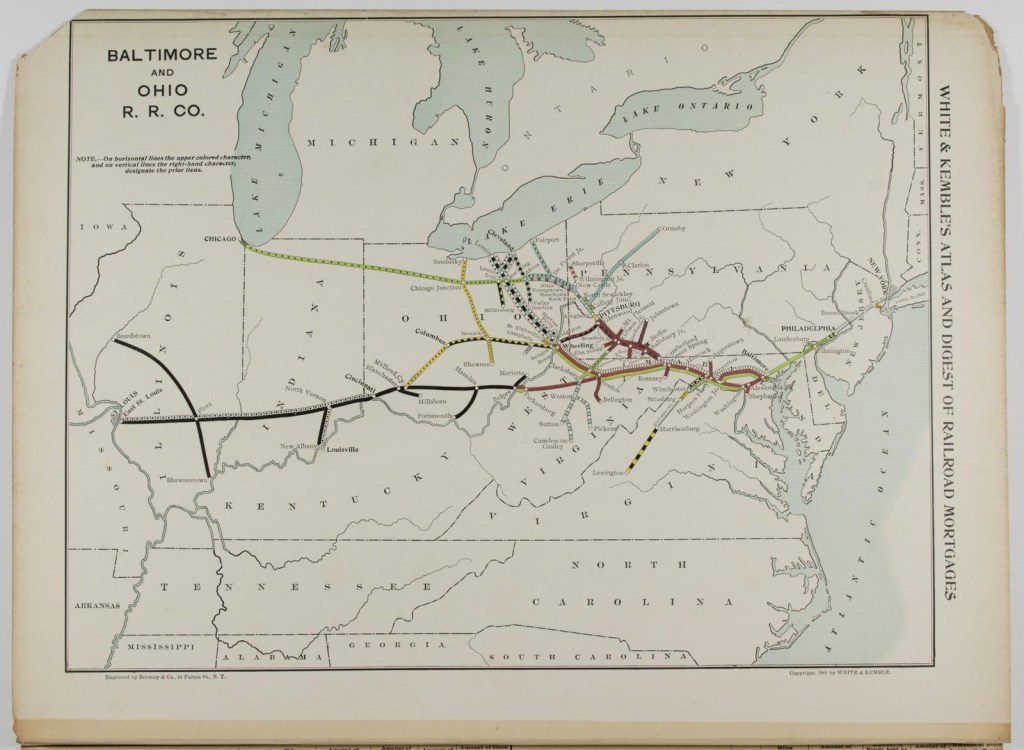

The most defensible interpretation of Tartaria, therefore, is not as a vanished empire but as an occluded mode of organization—one whose operational logic was systematically displaced by the rise of territorial sovereignty. For centuries, frontier confederations—tribal in function, guild-based in economic structure, and legalistic in collective identity—operated across steppe, riverine, and maritime zones as durable systems of coordination rather than as sovereign polities. Their authority derived from procedure, reputation, and negotiated jurisdiction, not from fixed borders or monopolized force. As territorial empires expanded and administrative rationalization intensified, these systems were not defeated in open conflict so much as rendered incompatible with the emerging grammar of state power.

This occlusion occurred through cumulative and often bureaucratically mundane transformations rather than singular acts of destruction. Cartographic conventions were revised to privilege fixed borders over corridors of circulation. Archives were reorganized to elevate centralized bureaucratic documentation above customary, portable, or oath-based legal regimes. Provisional towns, depots, and infrastructural nodes were rebuilt according to permanence-oriented regulatory codes that assumed sedentary populations and stable property relations. Indigenous and frontier populations were displaced, resettled, or administratively reclassified in ways that severed continuity with earlier organizational forms. The resulting historical record exhibits the telltale smoothness of compression, generating the persistent intuition that something extensive and coherent has been removed.

That intuition is correct. What is absent, however, is not a buried civilization or a suppressed monumental past, but institutional memory: the record of how non-territorial systems coordinated movement, mediated exchange, and stabilized identity beyond the jurisdictional assumptions of the modern state. The loss is epistemic rather than archaeological.

The enduring appeal of Tartaria lies precisely in its resistance to narrative closure. Properly reframed, it requires neither catastrophism nor speculative chronologies, and it invokes no concealed sovereigns. It requires only recognition that frontier systems produce evidentiary traces fundamentally misaligned with state-centered historiography—and that successor regimes possess strong incentives to overwrite, normalize, and simplify organizational forms that challenge territorial legibility.

Recovering this obscured complexity does not mean resurrecting a forgotten empire. It means reconstructing the history of coordination under conditions of porous borders, negotiable authority, and portable identity—conditions that were once widespread and structurally viable, but which have been rendered anomalous by the retrospective dominance of the nation-state.

That history is more contingent, more adaptive, and more recognizably human than the myth that replaces it. It is also, paradoxically, more difficult to erase, because it survives not in monuments or capitals, but in recurring patterns of organization that reappear wherever movement outpaces sovereignty.

Leave a comment