People often imagine tarot as a relic of ancient mystery traditions—something passed down by Egyptian priests, guarded by secret orders, and encrypted with cosmic meaning. In reality, none of this resembles how tarot actually emerged. Its origins lie in the social and material world of Renaissance Italy, where artisans, merchants, and noble patrons helped shape a new kind of card game. Tarot began not as an esoteric text but as a cultural artifact created for entertainment, shaped by the technologies and values of its time. Understanding this historical setting is essential if we want to grasp how tarot later became mythologized.

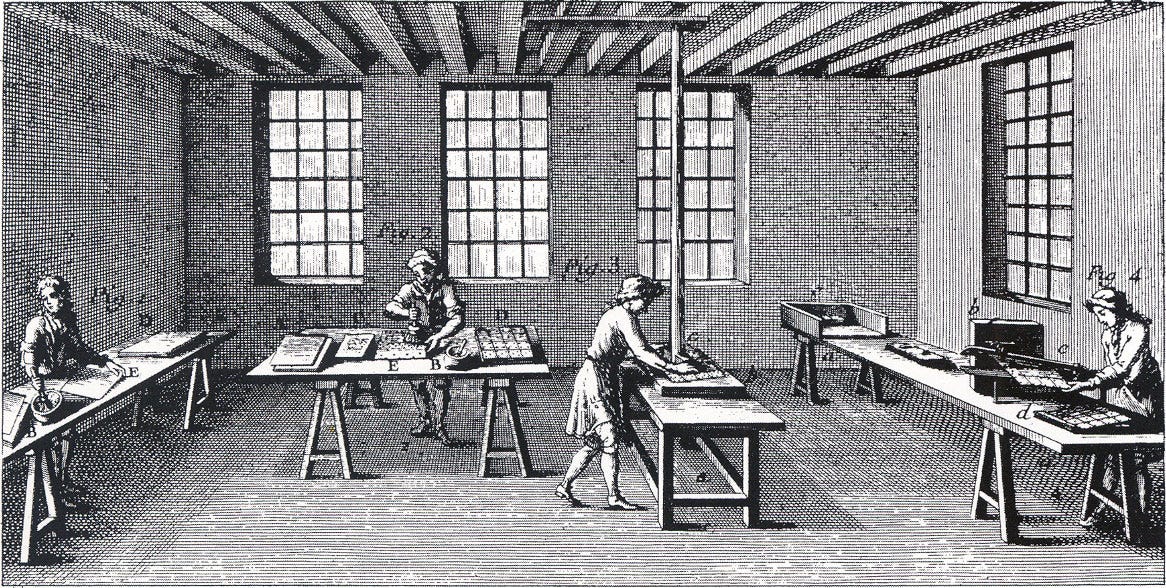

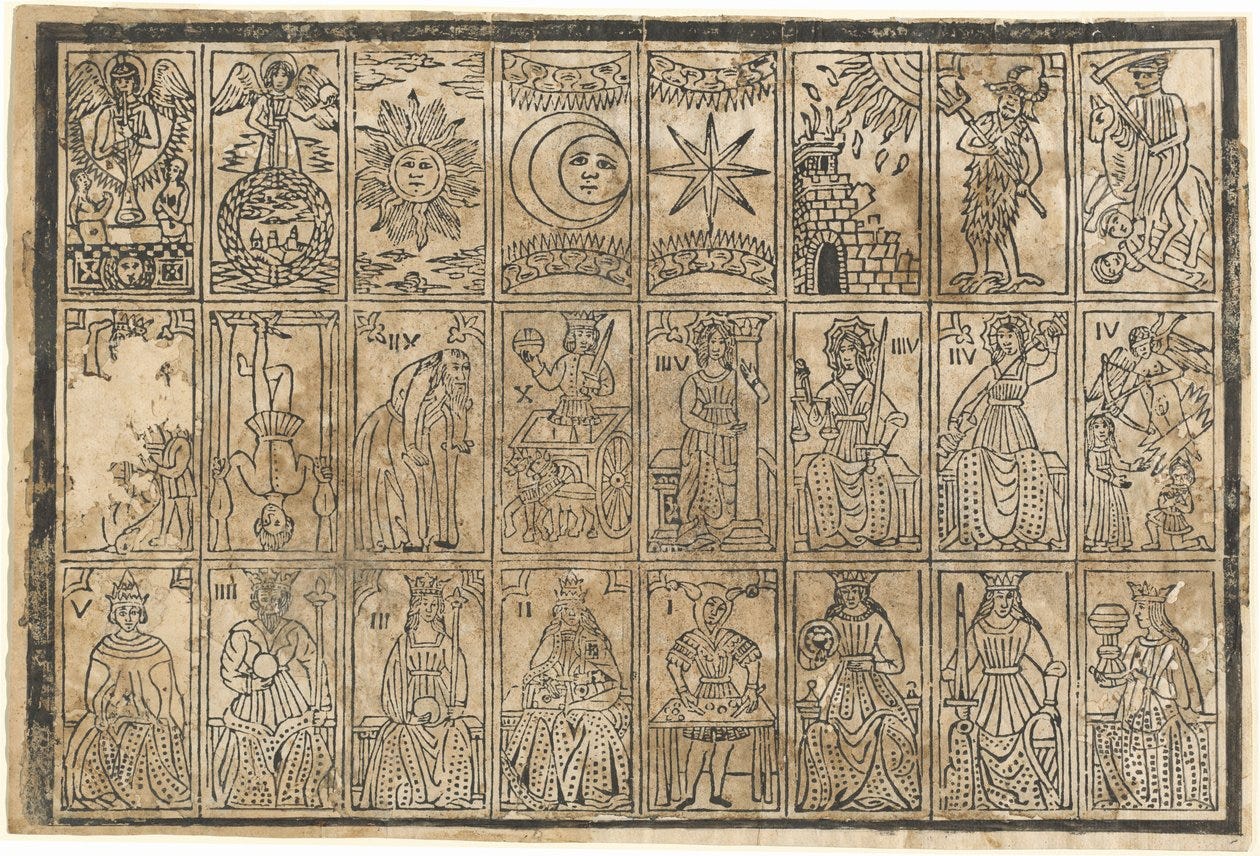

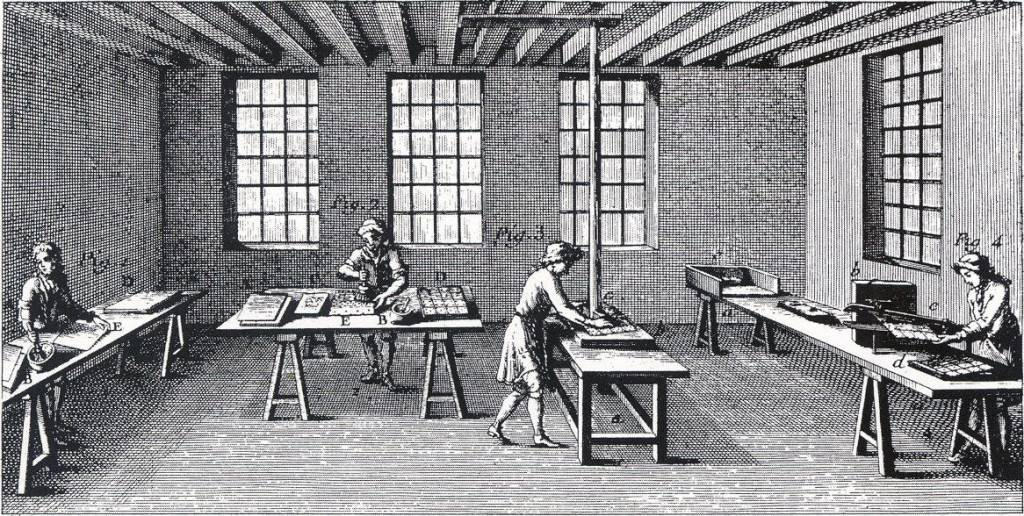

Playing cards entered Europe in the late fourteenth century, most likely through Mamluk Egypt. They traveled along commercial routes that also carried paper, mathematics, and luxury goods, and they quickly became a popular pastime across the continent. Early European decks featured familiar four-suit structures and court cards. They were both foreign and familiar—exotic in their motifs yet immediately adaptable to local gaming traditions. By the early fifteenth century, Italian workshops were mass-producing cards through woodblock printing, supplying a public eager for affordable amusements in cities that were rapidly expanding.

Within this environment, tarot emerged as an Italian innovation known as Trionfi. The earliest surviving decks were bespoke works commissioned by powerful families such as the Visconti and Sforza. These luxury decks combined standard suits with an additional set of trump cards. The trumps depicted allegorical figures that were pervasive in medieval and Renaissance visual culture: virtues, vices, figures of authority, scenes of fate and mortality, and personifications of cosmic or moral order. These images were not coded teachings. They belonged to the shared symbolic vocabulary of the period—imagery that appeared in church art, civic festivals, theatrical performances, and manuscript illustration. For an educated person in fifteenth‑century Italy, the meaning of these images was already established by the culture itself.

The game played with these cards resembled modern trick‑taking games such as bridge, and it was widely enjoyed across social classes. Tarot functioned as a structured form of leisure, a way to gather, compete, flirt, and socialize. Nothing about it suggested a prophetic or mystical function. The trumps existed to enrich gameplay, not to reveal destiny. If someone in Renaissance Italy had tried to use tarot to predict the future, the idea would have struck most observers as absurd.

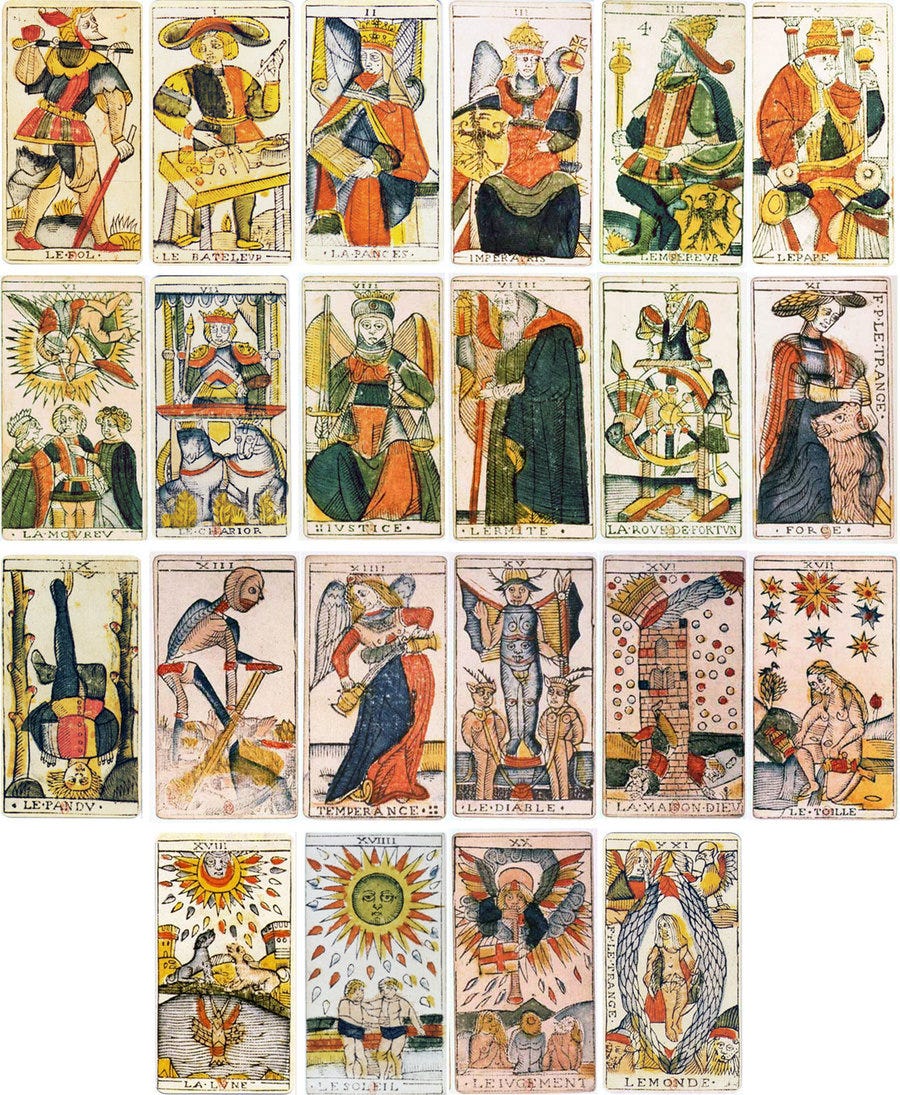

The shift toward tarot as a recognizable symbolic system begins not with mystics but with printers. Advances in print technology during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries produced standardized imagery, particularly in France. The designs now known as the Tarot de Marseille established the visual forms that would later become iconic: the Fool stepping forward with his pack, the skeletal figure of Death, the crowned Emperor, the Star pouring water, and other familiar images. These designs gained cultural traction not because they concealed hidden wisdom, but because they were widely circulated, inexpensive to reproduce, and consistent in form. Through mass printing, tarot effectively became a portable anthology of European allegory.

This is why tarot endured: not because it encoded esoteric knowledge, but because it reflected the worldview of the societies that used it. The Marseille cards condensed medieval and early modern ideas about fate, authority, virtue, and the human journey. Rather than acting as a tool for prophecy, tarot provided a symbolic shorthand for the themes that shaped everyday life. For centuries, card players recognized these images as part of their cultural environment, not as gateways to secret traditions.

For roughly three hundred years after its creation, tarot had no association with divination. It was neither a mystical system nor an occult text. It belonged to the same broad category as other forms of leisure—games shaped by artistry, craft, and the economics of printing. The idea that tarot contained ancient wisdom is a much later invention.

Recognizing this history helps us understand how symbols function. They rarely begin as sacred. Instead, they emerge from ordinary life and accumulate layers of meaning as different groups reinterpret them. Tarot is no exception. Its earliest forms operated as social objects—playable, portable, and repeatable. They reflected the society that produced them rather than claiming to predict or transcend it.

This matters if we want to approach modern tarot honestly. A clear view of tarot’s origins reveals it as a cultural technology built around shared archetypes, not a mystical device for divination. The transformation of tarot into an occult system happened much later, driven not by Renaissance cardmakers but by Enlightenment writers and nineteenth‑century occultists who reimagined old symbols to suit new ideological needs. Their reinterpretations would eventually redefine tarot’s place in modern culture—and that transformation is the subject of the next article.

Leave a comment