By the dawn of the twentieth century, tarot had already passed through two major transformations. First, it emerged in Renaissance Italy as an elegant card game reflecting the allegorical imagination of its age. Then, centuries later, it was reinterpreted by Enlightenment amateurs and Victorian occultists who projected ancient lineages onto imagery never meant to bear such weight. But if tarot’s first life was cultural and its second life was esoteric, its third life would be something else entirely. It would become modern.

This shift did not occur through a single event or a single thinker. Instead, it emerged from a convergence of intellectual, artistic, and commercial forces that reshaped Western culture in the twentieth century. Tarot moved from the margins into the mainstream—not because the cards changed, but because the world around them did.

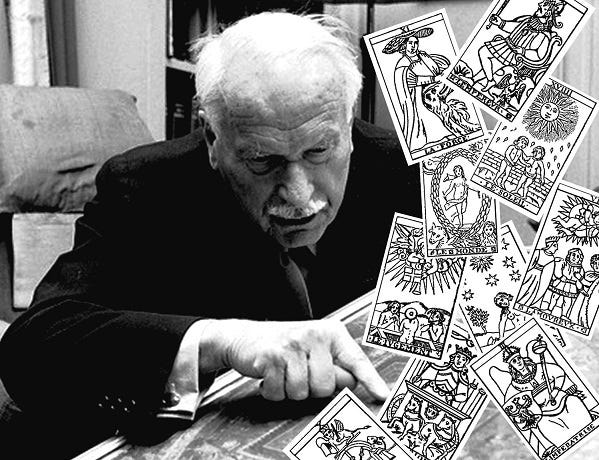

The first seeds of this transformation were planted, somewhat unexpectedly, in the growing field of depth psychology. Carl Jung, though not a tarot practitioner, saw in symbolic imagery a way to understand the human mind. Jung argued that universal patterns—“archetypes”—recur across cultures because they reflect structures embedded within the psyche itself. For Jung, images like the Hero, the Mother, the Hermit, or the Trickster were not esoteric secrets; they were psychological constants.

Tarot’s trumps, with their familiar themes of transformation, crisis, authority, and renewal, fit neatly into this framework. Jung occasionally referenced tarot in his seminars, noting that its images resembled those found in dreams and myths. He did not elevate tarot to the status of a therapeutic instrument, nor did he claim historical connections to alchemy or Kabbalah. But his openness to symbolic systems created intellectual permission for tarot to be seen not as a fortune-telling device but as a tool for introspection. Where occultists had sought cosmic correspondences, psychologists now saw narrative utility. Tarot could serve as a mirror—not of fate, but of the self.

It was an important shift. For centuries, tarot’s legitimacy had rested on claims of antiquity or hidden lineage. Jung made neither claim. He simply recognized that imagery, when arranged in meaningful sequences, invites reflection. Tarot’s authority began to move from myth to method.

The world that followed Jung was ripe for such a transition. The mid-twentieth century was a period of profound cultural reassessment. The traumas of two world wars, the disillusionment with institutional religion, and the rise of existentialist thinking left many searching for systems that could help articulate interior life. People wanted frameworks, not dogmas—something structured enough to guide thought, yet open enough to accommodate personal meaning.

Tarot offered exactly that. It was visually rich, thematically broad, historically intriguing, and flexible. It could be read in solitude or in conversation. It didn’t require clergy, initiation, or belief in metaphysics. It simply required attention.

By the 1960s and 70s, tarot had found fertile ground in the counterculture movements sweeping Europe and North America. These decades saw a dramatic rejection of traditional authority structures and a renewed interest in symbolic, experiential, and participatory forms of spirituality. Yoga, meditation, astrology, and I Ching readings proliferated alongside new communal movements and experimental art. Tarot fit this world with ease.

The cards migrated from esoteric lodges into living rooms, co-ops, college dormitories, and communal houses. Tarot readings appeared at music festivals, protests, and bookstores. They became woven into the visual vocabulary of the era’s underground press. Tarot stopped being a specialized interest and became a symbol of alternative spirituality itself.

The publishing world recognized this cultural moment. Companies that once treated tarot as an esoteric niche product began printing decks in mass quantities. Guidebooks were written for beginners as well as for those seeking deeper study. Pamela Colman Smith’s illustrations—now circulating widely in their Rider–Waite–Smith form—became a shared language among readers who had never heard of the Golden Dawn and had no need to. The deck’s imagery did what occult doctrine never could: it spoke directly to ordinary people.

This democratization sparked an explosion of new decks. Artists created visually distinct systems based on myths, folklore, feminism, Jungian psychology, nature, and multicultural symbolism. Each deck reinterpreted the structure established by Waite and Smith, using the seventy-eight-card format as a flexible container for new ideas. Tarot was no longer a fixed set of images but a framework—an adaptable template into which any symbol system could be poured.

Tarot’s increasing popularity also intersected with the growth of self-help movements in the late twentieth century. Readers used the cards not to predict external events but to explore internal states: emotional patterns, interpersonal dynamics, decision-making, self-concept. The language of tarot readings shifted accordingly. Instead of “What will happen?” people asked “What am I not seeing?” or “What do I need to understand about this situation?” Tarot became a means of organizing subjective experience—an accessible tool for reflection in an increasingly complex world.

By the 1980s and 90s, tarot had fully detached from its esoteric origins. It appeared in psychology textbooks, fiction, music videos, and advertising campaigns. It became a visual shorthand for intuition, self-inquiry, and the unknown. Its imagery entered fashion, graphic design, and pop culture. People who had never touched a deck could identify the Lovers, the Tower, or Death. Tarot was no longer a practice; it was an iconography.

This ubiquity came with costs. The more familiar tarot became, the easier it was for its history to be misunderstood. Many assumed that the Rider–Waite–Smith deck represented an ancient or universal symbolic system, unaware of its relatively recent creation. Others embraced the occult narratives of de Gébelin or Lévi without realizing those myths were products of imagination rather than evidence. Still others treated tarot as a mystical authority rather than a tool for personal interpretation.

Yet despite these confusions, tarot retained a remarkable capacity to adapt. It became secular without losing its depth, psychological without losing its mystery, artistic without losing its structure. It absorbed the changes of the twentieth century and integrated them into its interpretive possibilities. The cards survived because they could evolve without sacrificing their core function: to help people think in images.

This adaptability is what defines tarot today. It is not a relic of ancient civilizations nor a closed esoteric system. It is a modern symbolic instrument—a language for exploring experience, asking questions, and externalizing thought. Its power lies not in any hidden doctrine but in its capacity to facilitate meaning-making across cultures, eras, and individual perspectives.