When we talk about power today, we almost always default to the wrong shape.

We imagine pyramids: chains of command, top‑down hierarchies, a Don at the top and soldiers beneath, authority flowing downward like gravity. That model feels intuitive, but it fails to capture how durable power actually operates in complex societies. Pyramids describe management. They do not describe sovereignty.

The older model is not a pyramid.

It is a field.

And at the center of that field is not a bureaucratic administrator or a charismatic personality, but something far older and structurally precise: a monarch—a Rex, a Dominus, a crowned figure whose function is not to dominate from above, but to serve as the gravitational anchor around which the entire system orbits. Their power is not linear. It is orbital—generated by what moves around them, not by what they force downward.

The Monarch as Center of Orbit

The word monarch does not mean “tyrant” or “boss.” It means single principle—the axial point around which an entire system coheres.

But that center has no intrinsic force. A monarch alone is inert. Their significance emerges only when something moves around them—when people, offices, rituals, traditions, and institutions begin to orbit and reflect them.

In this sense, the deeper structure of monarchy resembles an atom far more than a genealogical line. The monarch is the nucleus: dense, symbol-laden, gravitational. Around them circulate layers of attendants, officials, watchers, and cultural functions—each maintaining its own distance, rhythm, and form of contribution. Their motion animates the center.

Remove the orbits, and the nucleus collapses into irrelevance.

This is why imperial authority was never defined by a throne alone. It lived in the house, the court, the ceremonial body, the retinue—the whole breathing architecture of continuity. The monarch did not merely oversee this structure; their very identity and power were generated by it, the same way a star is made luminous by the forces that surround and sustain it.

The Crown as Diagram, Not Decoration

This is where Byzantine imagery becomes crucial.

Byzantine crowns are not merely ornate. They are diagrammatic instruments, visual schematics encoding how imperial authority was structured, synchronized, and continually renewed.

The gemstones are not decorations. Each one is a node—faceted, reflective, deliberately positioned. Icons and saints encircle the emperor’s head not as devotional illustrations, but as representations of orbiting layers of continuity. They signify the court, the clergy, the bureaucracy, the military, and the cultural memory that collectively maintain the emperor’s function. In an empire where literacy, ritual, and law were deeply intertwined, the crown served as a compressed cosmology—an executable diagram of power.

The crown is a literal map of the forces that stabilize the monarch. It is political theology rendered in metal and light.

Saints operate according to the same logic. A saint was never a solitary figure. A saint accumulated orbit—followers, shrines, feast days, relic traditions, miracle narratives—forming a self-sustaining informational and social network that survived long after the individual’s death. Their influence persisted because the structure around them persisted; the orbit generated the sanctity, not the other way around.

Haloes, then, are not symbols of goodness. They are visual shorthand for stable orbit, a graphic representation of the forces that continually circulate around a figure and keep their significance alive across generations. A halo marks not purity, but coherence—a sign that a person has become the center of a synchronized attention-field.

The Byzantine emperor, crowned in jewels and saints, sat at the center of a living matrix of institutional memory, ritual timing, legal precedent, and coordinated attention. What we now read as symbolic ornamentation once functioned as infrastructure—a visible interface for an invisible system, a crown that did not merely adorn the emperor but operated him.

Empire as Clothing

In this model, empire is not primarily territory. It is attire—a layered operating system worn by the monarch to extend their presence across distance, bureaucracy, and historical time.

The army is a garment.

The bureaucracy is a garment.

The priesthood is a garment.

These are not poetic metaphors. Each layer functions like specialized armor—protective, communicative, and amplifying. Together they project the monarch’s authority outward and pull information inward. The emperor becomes a single human node supported by a vast exoskeleton of institutions, traditions, and coordinated observers.

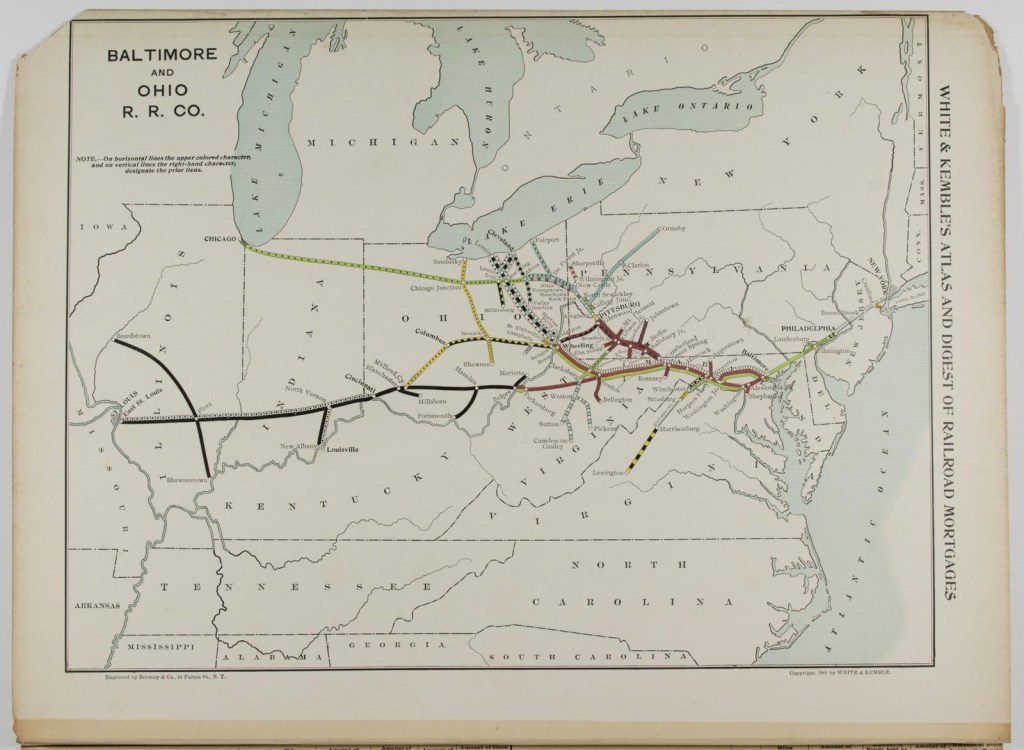

In practice, this “suit” allowed a monarch to perceive far more than any one person could. Intelligence networks, military scouting systems, clerical correspondences, court gossip, ritual specialists, legal archives—these were the empire’s sensory organs, transmitting signals back to the center.

The emperor does not need to see everything directly because the empire sees on his behalf. What appears as sovereign intuition is often the compression of countless observations moving through a synchronized system.

This is the deeper meaning of “watchers”: not individuals who merely observe, but the distributed architecture of vision—eyes, roles, channels, rituals, and institutions—that makes the monarch perceptible and makes monarchy possible.

Watchers and the Synchronization of Sight

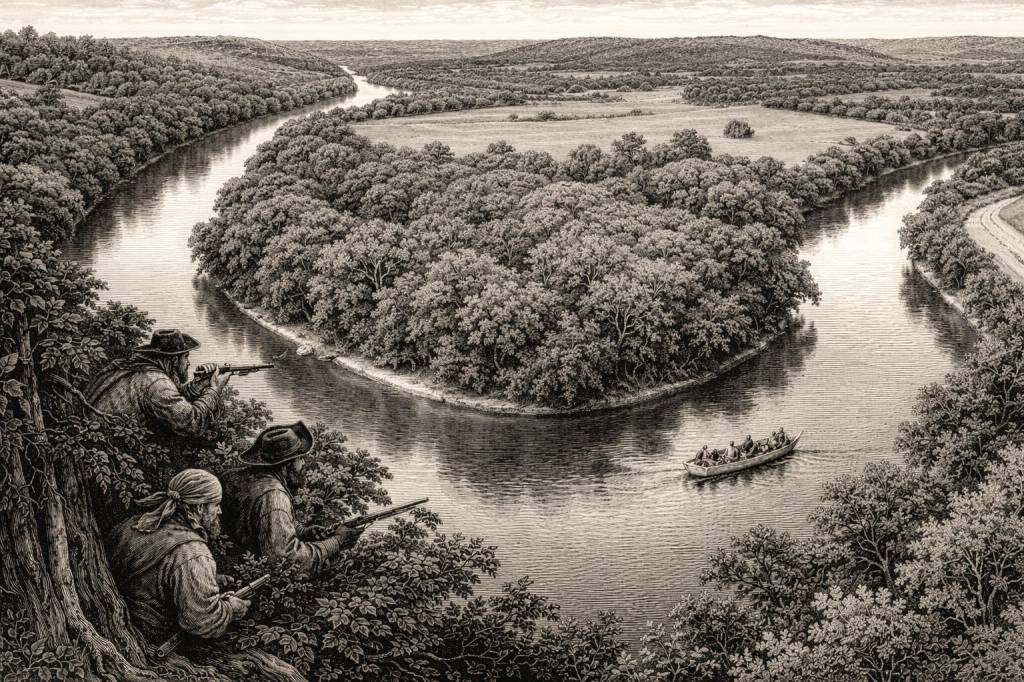

A watcher is not merely someone who observes. A watcher is someone whose attention is synchronized with others—integrated into a coordinated perceptual system that extends far beyond individual eyesight.

In a mature empire, information does not drift randomly. It flows through watchers the way electrons move through shells: patterned, hierarchical, and timed. Every observer occupies a specific “layer,” and their observations resonate inward according to the system’s established rhythms.

When something occurs at the empire’s edge—a border dispute, an omen, a rumor, a shift in weather—it is not experienced as a distant event. Its perception begins a cascade. It moves pupil to pupil, messenger to messenger, report to archive, reflection to council, until it reaches the sovereign. By the time the emperor becomes aware of an event, the information has already been filtered, sequenced, contextualized, and stabilized.

In a fully tuned system, this propagation feels instantaneous, as though the empire itself were a single organism.

To the emperor, this manifests as oracle—not prophecy, but heightened presence. It is the sensation of receiving the world with minimal delay, of perceiving distant events as though they were unfolding nearby.

A Palantír does not reveal the future. It erases distance. It makes the far feel near. This is precisely what synchronized watchers accomplish: they collapse space into immediacy and turn a sprawling territory into a single field of vision.

Not prophecy, but presence.

A Palantír does not show the future. It collapses distance. It makes the far feel near. That is what synchronized watching does.

Why Crude Rituals Fail

This is why later, degraded attempts to replicate power through simple ritual—five watchers arranged in a pentagram, a single dramatic initiation—are fundamentally insufficient. These forms try to imitate geometry without understanding time. They mimic the shape of power but not the tempo that sustains it.

A Byzantine emperor’s authority did not emerge overnight. It was cultivated across generations. His watchfulness extended through calendars, feast cycles, military campaigns, legal precedents, tribute routes, provincial reports, and the dense layering of liturgical and bureaucratic time. Power accumulated not through spectacle but through temporal depth—the slow, recursive accretion of synchronized observation and institutional memory.

To someone inside that system, the effect would resemble time travel—not because time was broken, but because delay had been engineered out of the imperial network. Information arrived so quickly, so continuously, that the emperor seemed to stand a few seconds ahead of the world.

The emperor does not predict events. He simply receives them first—because an entire civilization is watching, timing, and thinking on his behalf.

Modern Eyes, Ancient Structure

What changes in the modern world is not the structure—it is the medium through which the structure operates.

Today, millions of eyes exist everywhere, always on. Cameras, phones, sensors, feeds—an entire lattice of recording and transmission technologies. The watcher system has not vanished; it has been fully automated and massively expanded.

When something happens, it is registered instantly. Circulated instantly. Amplified instantly. The delay that once defined premodern empires has collapsed into near-zero.

The sovereign no longer relies on messengers. The empire has become self‑observing, a continuous feedback loop in which society watches, archives, and interprets itself in real time.

The jewels have become pixels.

The saints have become icons.

The crown has become a network.

The medium has shifted—but the underlying architecture of power and perception remains unchanged.

The Crowned Ones

In this framework, elites are not merely wealthy or influential individuals. They are crowned positions—symbolic nodes suspended within a broader social field, maintained by orbit, recognition, ritual, and institutional continuity. What distinguishes them is not personal charisma or exceptional talent, but their placement within an enduring configuration of attention and authority.

Their distinctiveness does not arise from personal attributes.

It derives from the architecture that surrounds, legitimizes, and continually reproduces them. A crowned figure is not meaningful in isolation; they matter because a system has been built to sustain and amplify their presence.

A monarch, in this sense, is not positioned above the system.

They constitute the system in its most concentrated, legible form. They are the visible condensation of a much larger, slower-moving structure—law, ritual, memory, administration, lineage, and surveillance—brought into a single point of focus.

What This Reveals

The ancient “stargate” was never a mechanical apparatus. It was a crowned human embedded within a synchronized network of watchers, functioning as a temporal and interpretive engine. Their role was to compress delay, stabilize meaning, and coordinate collective action across distance and time.

The gate was not something one passed through.

It was something one perceived through—a human interface for navigating the world’s complexity.

And the crown—jeweled, faceted, radiant—was not ornamental excess. It encoded hierarchy, continuity, and orbit. It signaled that the wearer had entered the position where all lines of sight converge.

It was a circuit: a visible interface for the invisible infrastructure of attention, timing, memory, and authority.

Leave a comment