There are moments in American history when multiple systems come online at once — religion, commerce, geography, intelligence. Not gradually. Not politely. They activate together, compressing decades of change into a few volatile years. The 1820s–1830s frontier is one of those moments.

America is still unfinished. Federal authority is thin. Rivers function as highways. Land is speculative. Faith is mobile. Capital is hunting new corridors. And right in the middle of this turbulence appears a strange convergence of names, routes, and timelines — especially when you place Jedediah Smith, Joseph Smith Jr., and Hyrum Smith side‑by‑side.

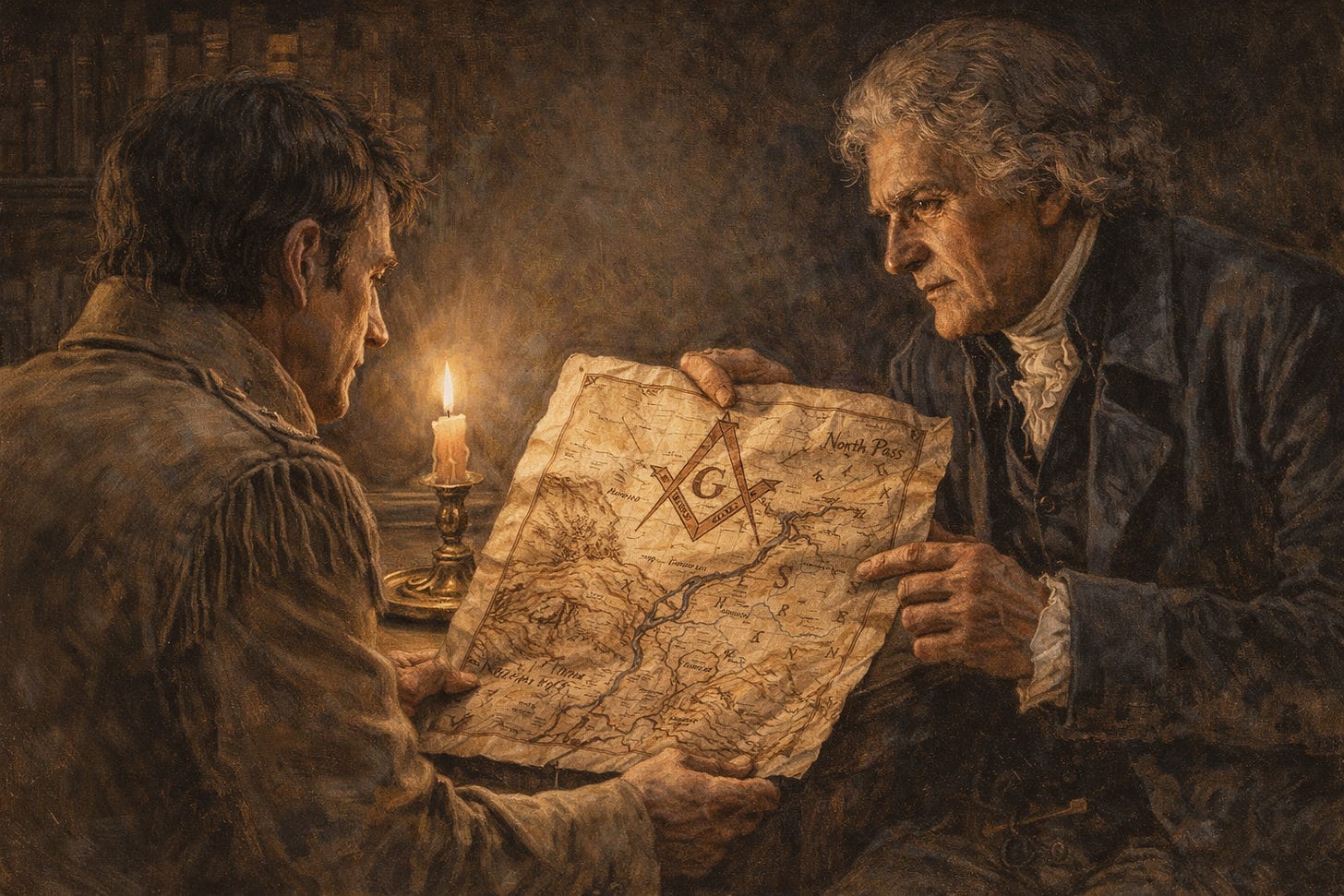

Not because they’re secretly the same person — but because they are operating on different layers of the same expansion engine. One is mapping terrain. One is organizing belief. One is helping consolidate communities. Exploration, finance, and religion begin to synchronize.

What looks like coincidence starts to resemble choreography.

Three Smiths, One Decade

Let’s start with dates:

- Jedediah Smith — born 1799

- Hyrum Smith — born 1800

- Joseph Smith Jr. — born 1805

Three births inside a single frontier generation. All coming of age in the same volatile ecosystem: revivalist Methodism, folk Christianity, itinerant preaching circuits, land speculation, and a rural culture steeped in visions, signs, and buried treasure. Joseph Smith’s family — especially his father — participated in treasure‑seeking circles that used seer stones, divining rods, and ritual digging. This wasn’t fringe behavior in early America. It was a recognized subculture, a hybrid of Protestant mysticism, Old World folk magic, and frontier scarcity — part spiritual practice, part economic survival strategy.

By the 1820s, Joseph Smith Jr. is already gathering followers and producing revelations. By 1830, he formally founds what becomes the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter‑day Saints. Within only a few years, Joseph and Hyrum are no longer simply preaching — they are organizing territory. Settlements in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois are coordinated at scale. Militias are formed. Land is consolidated. Migration is systematized. What begins as prophecy rapidly takes on the structure of a paramilitary settlement network, complete with command hierarchies and population management.

This is pre–Civil War America: federal authority is thin beyond the Appalachians. Speculators are buying entire counties on paper. River ports function as financial gateways. Private militias outpace government enforcement. The frontier operates as a power vacuum where religion, commerce, and violence coexist.

And everything — people, goods, money, rumors, and influence — moves on the Mississippi.

Everything.

Meanwhile, Another Smith Is Mapping the Continent

At the exact same time Joseph Smith is organizing followers in the Midwest, Jedediah Smith is doing something very different:

He’s walking America.

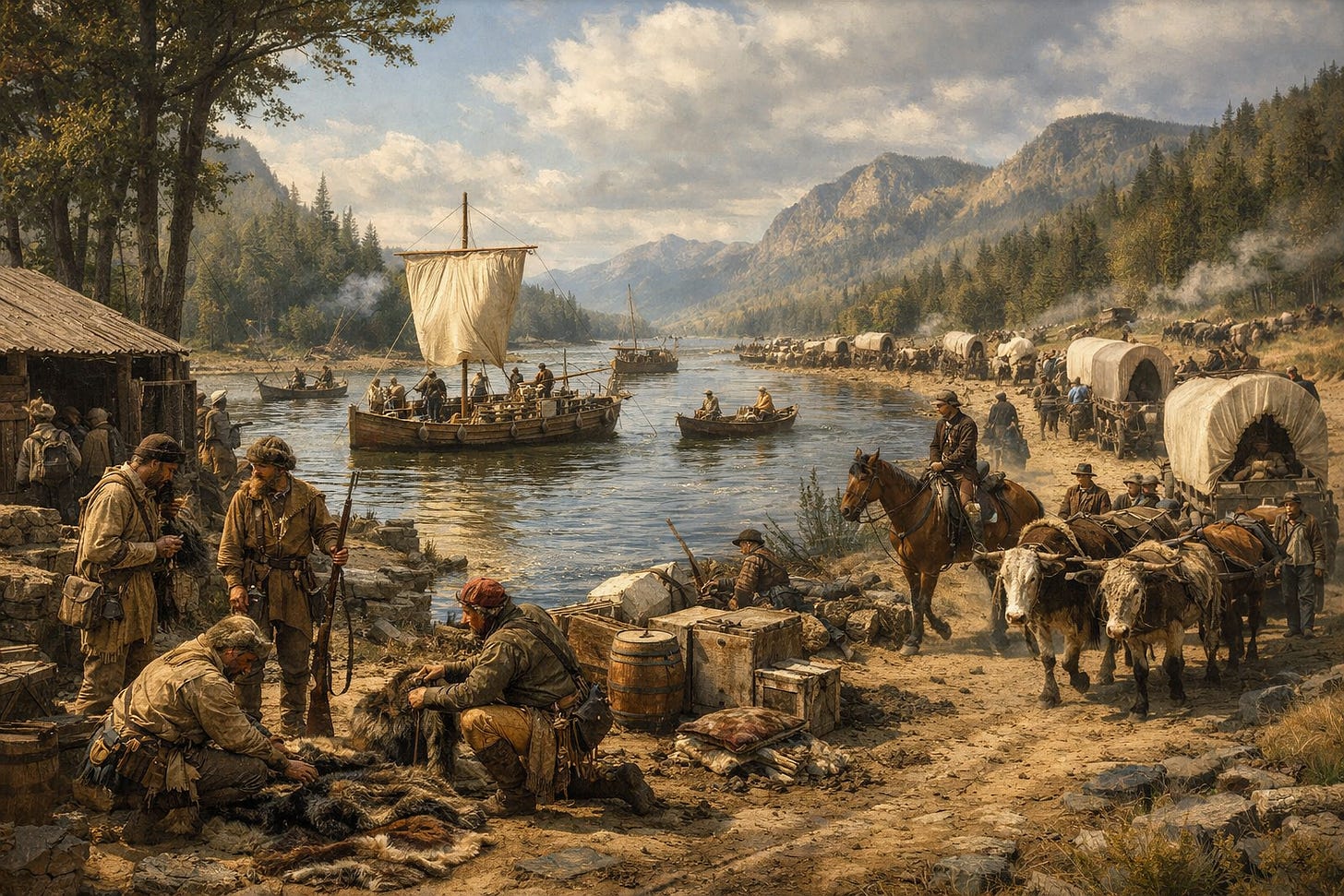

Jedediah becomes one of the first Americans to cross the continent overland, opening routes through the Rockies, the Great Basin, and California. He works for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, operating inside the brutal world of mountain men, river brigades, and annual rendezvous.

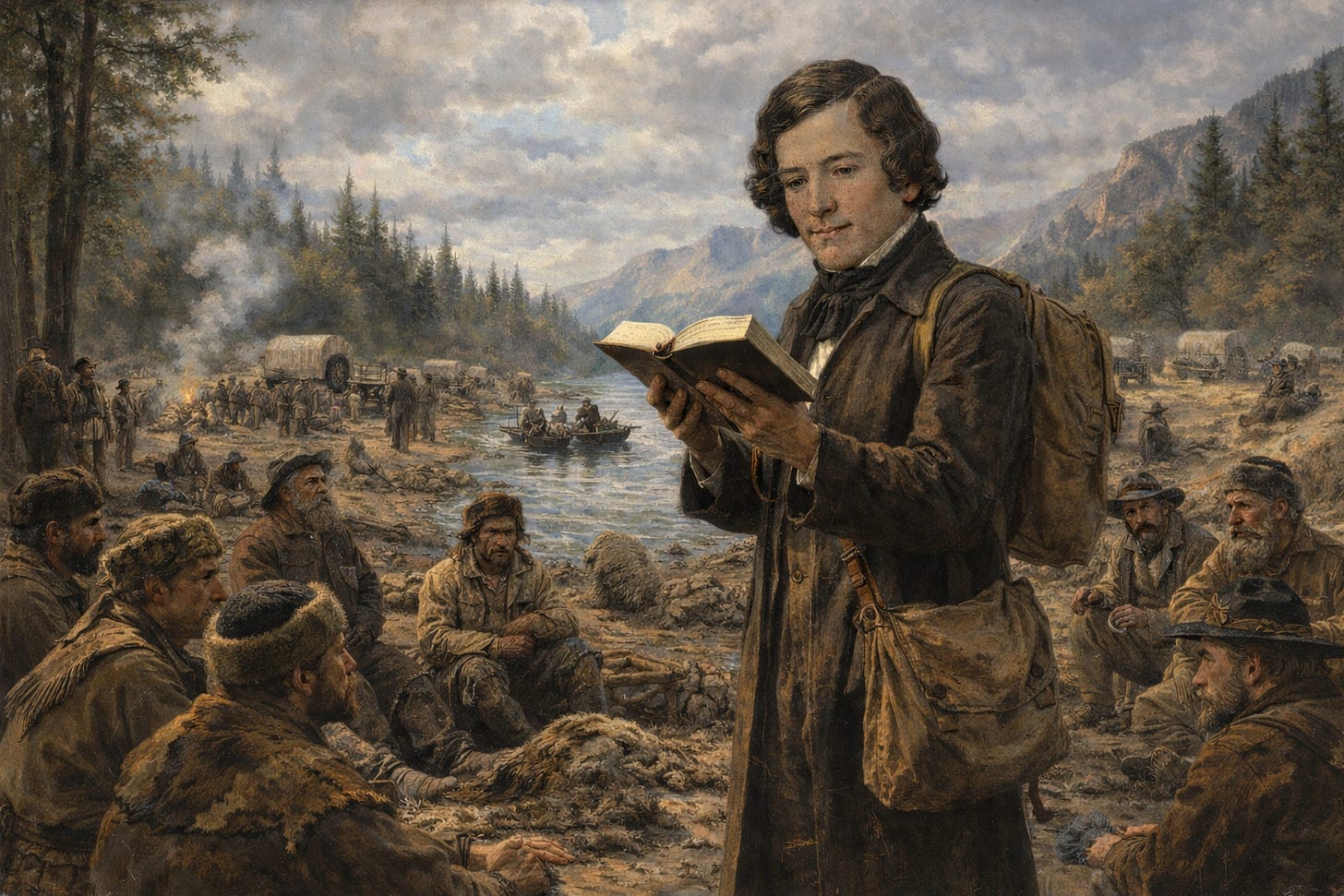

He earns a reputation as “the Bible man” — deeply religious, disciplined, almost ascetic — carrying scripture into places no Protestant preacher had ever been. Contemporary accounts describe him stopping to read from the Bible in remote camps, mediating disputes, and preaching wherever people would listen. He even spends time evangelizing in the Salt Lake region decades before it becomes Mormon territory — an early Protestant presence in what will later become Utah.

This matters, because while Jedediah is moving scripture westward on foot, Joseph Smith is moving revelation eastward through print and testimony. Between 1823 and 1829 — the same years Jedediah is opening interior corridors — Joseph claims to recover the gold plates, translates them, and prepares the Book of Mormon for publication. The prophetic artifacts enter circulation first; the church formally follows in 1830.

Two parallel movements: one mapping land, the other manufacturing sacred authority.

The Rocky Mountain Fur Company pioneers the rendezvous system: instead of hauling pelts east every year, trappers stay in the mountains while supply caravans meet them at prearranged points. It’s decentralized extraction — frontier special‑forces logistics.

And crucially: this network discovers South Pass, the wide, low‑elevation corridor through the Rockies that quietly becomes the most important land gateway in North America.

At first, South Pass is a trade secret.

Because fur is money.

Whoever controls access to the beaver basins controls the economy.

1830–1831: The Hinge

1830 — Mormonism is formally founded.

Early 1831 — Jedediah Smith petitions for support to publish his western maps and expand trade. He is attempting to formalize what he already carries in his head: firsthand geographic intelligence from thousands of miles of interior travel.

He’s denied.

May 1831 — Jedediah heads east along the Cimarron Cutoff, traveling with a small party through territory he had already survived multiple times.

He never arrives.

No recovered body.

No marked grave.

No surviving eyewitnesses who actually saw him die.

Instead, his death enters the record secondhand — reported not by family, not by companions, but by his employer, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. The same company holding his maps, journals, and commercial knowledge.

That alone should raise eyebrows.

There is no contemporary coroner’s report. No physical remains presented. No independent verification. Only a brief commercial notice passed along trading networks: Jedediah Smith is gone.

“Indians got him” becomes the official explanation — a frontier catch‑all that requires no evidence and invites no follow‑up.

A man who crossed deserts, survived grizzly attacks, escaped captivity multiple times, and navigated unmapped mountain ranges simply vanishes weeks after being denied funding to publish his routes.

And that’s where the paper trail ends.

No closure.

No inquiry.

Just disappearance.

South Pass, Astor, and the Eastern Money Machine

While Jedediah is producing raw geographic intelligence on the ground, another system is already waiting to monetize it.

Back east, John Jacob Astor runs the American Fur Company — not simply a trading house, but a vertically integrated empire. It controls transport, extends credit to trappers and agents, secures federal licenses, negotiates Native trade contracts, dominates Great Lakes shipping lanes, and funnels pelts through New York export houses into global markets in London and Canton.

Astor does not explore.

He aggregates.

He builds a clearinghouse where information itself becomes a commodity. French voyageurs, former British traders, Native intermediaries, military survey reports — all of it flows east. Maps are copied. Routes are compared. Risks are priced. Intelligence is absorbed and centralized.

Chicago is not random in this equation. Long before it becomes synonymous with twentieth‑century crime syndicates, it functions as an inland nerve center. The French had established it as a portage corridor linking the Great Lakes to the Illinois River. British traders had used it to move furs south and east. After the Louisiana Purchase, the corridor becomes strategically American — a hinge between empire and republic.

Astor understands this immediately.

He approaches Thomas Jefferson in the early 1800s with a proposal: allow an American monopoly to dominate the interior fur trade, and British commercial influence in the newly acquired Louisiana Territory can be displaced without open war. Commerce becomes policy. Trade becomes territorial consolidation.

Jefferson is receptive. The Louisiana Purchase has doubled the size of the United States on paper, but paper means nothing without economic occupation. Fur posts become outposts of sovereignty.

Then comes the War of 1812.

British North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company operations are disrupted within U.S. boundaries. Canadian competition is forced out of key corridors. Astor steps into the vacuum, consolidating licenses and absorbing weakened competitors. The American Fur Company expands its grip.

Logistically, the system is ruthless and efficient. Trade goods — firearms, blankets, metal tools, textiles — are shipped west via the Great Lakes. Credit is extended to Native trappers in advance of the season. Pelts are collected at depots, transported back through Chicago, moved east to New York, graded, bundled, insured, and shipped across the Atlantic. The flow of information follows the flow of fur.

Astor’s New York office becomes more than a warehouse. It functions as an intelligence exchange. Reports from the frontier are analyzed not for romance, but for margin.

This is why South Pass matters.

Once a northern corridor through the Rockies is reliably identified, the advantage shifts permanently toward whoever can industrialize it. Smith’s wagon trains and rendezvous networks are agile, but they are local. Astor’s Astoria outpost on the Pacific coast, his Great Lakes fleets, and his global shipping contracts dwarf any single mountain operation.

Jedediah’s Utah‑adjacent preaching circuits and Rocky Mountain intelligence may open doors, but Astor’s network decides which doors stay open. The eastern money machine outpaces the frontier scout every time.

So you get a layered symmetry:

Astor consolidating secondhand maps, trade data, and shipping routes in New York.

Smith generating firsthand terrain intelligence in the Rockies.

French and British corridor knowledge absorbed into an American monopoly.

Everything converging through Chicago.

Headquarters and forward scouts.

Different men.

Same expanding system.

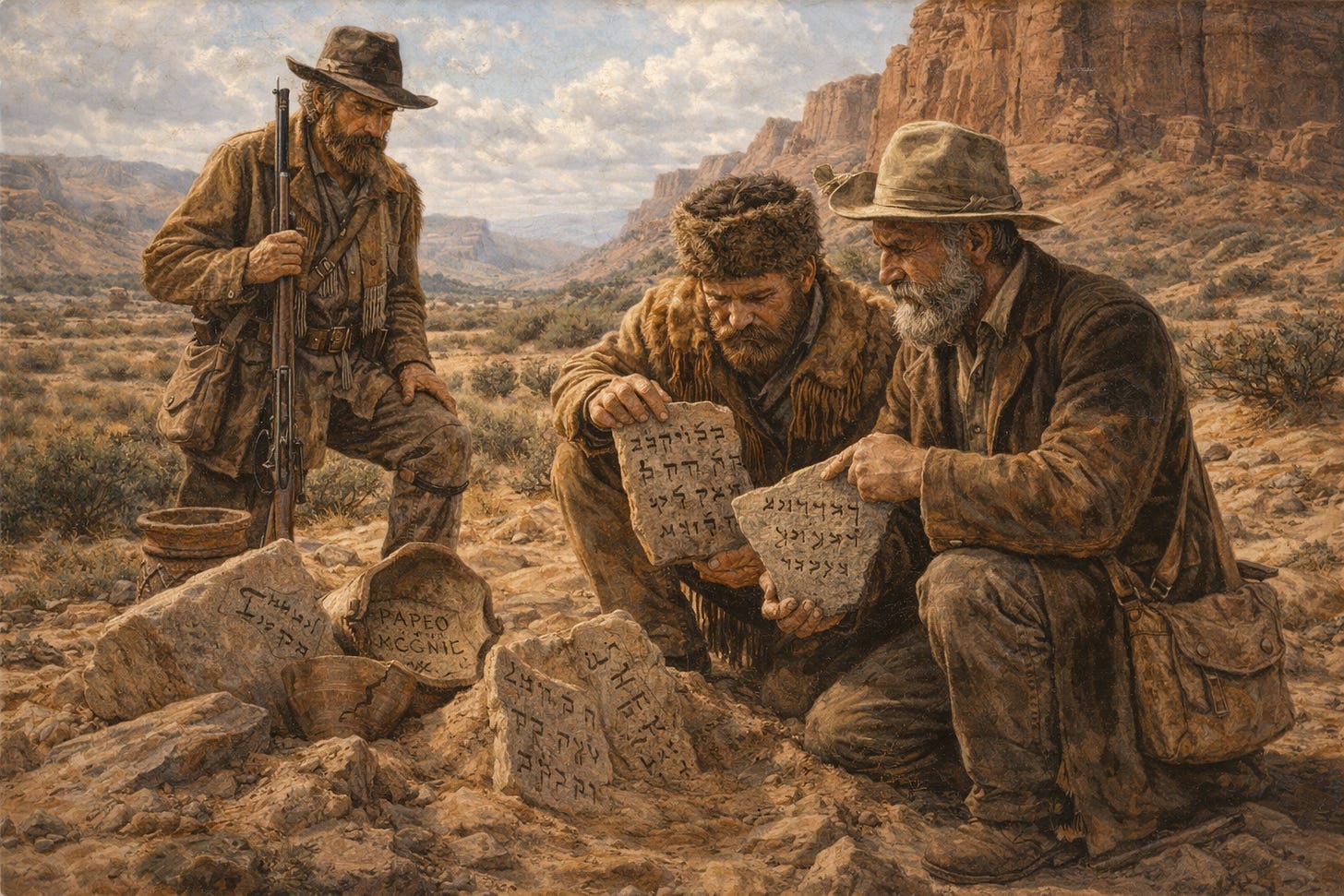

Relics, Religion, and Treasure

Back in Joseph Smith’s world, another strange layer emerges. Early Mormonism is obsessed with relics, plates, ancient scripts. Treasure‑hunting culture doesn’t disappear — it mutates into sacred archaeology. What began as folk digging becomes institutionalized collection.

After Joseph’s death, Brigham Young carries this impulse west. Utah doesn’t just become a refuge for displaced believers — it becomes a custodial zone. Records, artifacts, family genealogies, sacred objects, and frontier discoveries are centralized under church authority. The migration to the Great Basin functions as both population movement and archival consolidation. What couldn’t be protected in Illinois or Missouri is physically removed from federal reach and re‑anchored in the desert.

Later, institutions like the Smithsonian quietly accumulate huge numbers of so‑called “paleo‑Hebrew” artifacts and frontier relics, many later deemed fraudulent. But the pattern repeats across both church and state:

Collect first.

Authenticate later.

It looks less like naïve belief and more like relic acquisition under uncertainty — a race to secure cultural material before anyone else can.

Secure the artifacts.

Sort out truth afterward.

Utah becomes the long‑term vault. New York handles capital. Chicago routes logistics. The Rockies absorb the overflow.

Put it all together and the overlap becomes hard to ignore:

Joseph Smith activates a mass religious movement along the Mississippi.

Jedediah Smith opens the western corridors.

Astor’s network absorbs the routes into eastern finance.

South Pass quietly shifts from trapper secret to future migration highway.

Jedediah disappears.

Mormon settlement accelerates.

Brigham Young consolidates the western archive.

Both Smiths die young.

Both operate at the frontier edge of American expansion.

Both sit inside systems far larger than themselves.

Even Jefferson’s Earlier Scout Fits the Pattern

You can rewind this story another twenty years to Meriwether Lewis, sent west by Jefferson on what history politely labels exploration, but what functioned in reality as strategic reconnaissance. Lewis was tasked with surveying rivers, mountain passes, Native alliances, and interior trade potential long before mass settlement was politically viable. His expedition was about inventorying a continent — determining where commerce could flow, where populations could move, and which corridors would someday become permanent infrastructure.

Lewis later dies under strange circumstances on the Natchez Trace, isolated, his papers scattered, his findings quietly absorbed into government archives. He had Masonic ties. He was mapping corridors before settlers arrived. And his fate mirrors a pattern that keeps repeating: the scout goes first, the system follows.

This is the underlying architecture of early American expansion. Reconnaissance precedes migration. Intelligence precedes ownership. Exploration establishes possibility, trade converts possibility into profit, finance consolidates profit into power, and religion mobilizes bodies to occupy what capital has already mapped.

What looks, in retrospect, like rugged individualism was actually coordinated sequencing. Explorers generated terrain intelligence. Traders converted geography into commodities. Financiers transformed commodities into capital. Religious movements organized populations. Corridors hardened into destiny.

Fur comes first. Then people. Then rail.

The frontier was never chaos. It was choreography — a distributed system of scouts, merchants, bankers, and prophets moving in loose formation toward the same outcome.

By the time Chicago becomes famous for gangsters, the template is already more than a century old: centralized finance paired with decentralized operators, quiet enforcement wrapped in plausible deniability. Astor wore a suit. The mountain men wore buckskins. The prophets brought families.

The curious timeline of Mr. Smith isn’t about identity. It’s about synchronization.