Tarot’s reputation as a repository of ancient mystical wisdom is a relatively recent construction. The images themselves originated in Renaissance Europe, but the belief that they conceal esoteric teachings from Egypt, Kabbalah, or other primordial traditions was shaped centuries later. To understand how tarot acquired this new identity, we must examine the intellectual and cultural forces of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—an era defined by expanding global curiosity, Romantic imagination, and the rise of organized occult movements seeking legitimacy through invented antiquity.

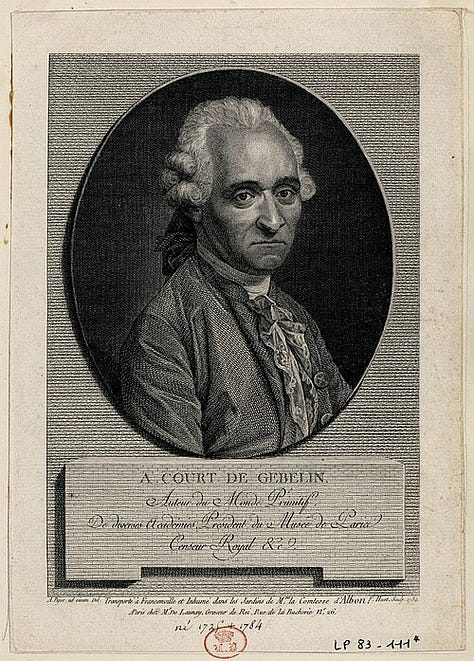

The pivotal moment occurs in 1781 when Antoine Court de Gébelin, a Protestant pastor and amateur scholar, published a speculative essay claiming that tarot preserved fragments of the ancient Egyptian “Book of Thoth.” This assertion was presented with confidence but without evidence. Egyptology did not yet exist, hieroglyphs remained undeciphered, and de Gébelin had no access to the primary sources that would eventually illuminate Egyptian religion. His argument rested instead on the Enlightenment fascination with origins—an intellectual climate that encouraged the belief that hidden wisdom survived in unexpected places. To de Gébelin, the strangeness of tarot’s images suggested antiquity, and antiquity implied concealed meaning.

Although unfounded, his interpretation resonated with a European audience captivated by the idea of recovering lost civilizations. Egyptian artifacts were entering museums and private collections, travel accounts circulated widely, and speculation about an ancient universal religion became fashionable. In this environment, de Gébelin’s claims helped transform tarot from an ordinary card game into a candidate for deep symbolic inquiry.

Éliphas Lévi advanced this transformation dramatically in the mid‑nineteenth century. A former seminarian turned occult philosopher, Lévi possessed both the imagination and the intellectual ambition to synthesize disparate traditions into a cohesive system. He connected tarot’s twenty‑two trumps to the twenty‑two letters of the Hebrew alphabet, the pathways of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, and a complex network of astrological and numerological correspondences. Historically, these associations are baseless—no evidence indicates that Renaissance cardmakers had Kabbalah in mind. Yet Lévi’s reconstruction was compelling precisely because it offered readers a unified symbolic worldview at a time when industrialization and scientific rationalism were reshaping European society.

By the late nineteenth century, Europe was experiencing a flourishing occult revival. Secret societies, esoteric lodges, and spiritualist movements proliferated across France, England, and Germany. Many of these groups sought an aura of authority by claiming access to ancient wisdom traditions. Tarot, already reimagined by de Gébelin and systematized by Lévi, proved an ideal foundation for constructing elaborate metaphysical curricula.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, founded in 1888, completed tarot’s transition from a historical artifact to an esoteric textbook. The Golden Dawn reorganized the deck to align with its initiatory degrees and ritual structure, integrating tarot with astrology, Kabbalah, Hermeticism, and ceremonial magic. The cards became structural components of a broader philosophical system, valued less for their historical origins than for their usefulness as instructional diagrams.

This reinterpretation did more than add symbolic layers—it displaced the historical meaning of tarot almost entirely. Medieval allegories once rooted in the social, religious, and artistic environment of the fifteenth century were recast as expressions of cosmic law. The Fool and the Magician evolved from recognizable Renaissance figures into archetypes of spiritual initiation. The Wheel of Fortune shifted from a moral allegory to a metaphysical principle. The original cultural context was overshadowed by an esoteric framework that claimed, incorrectly, to be recovering ancient knowledge.

What makes this transformation remarkable is not the act of reinterpretation itself—symbols are constantly reimagined—but the insistence that these reinterpretations represented an unbroken lineage. The occultists of this period believed they were restoring an authentic tradition, yet they were in fact inventing one. Their systems were imaginative constructions, retroactively projected onto imagery never intended to carry such meanings.

Still, these inventions endured because they offered something compelling. The emerging myth of tarot as a timeless symbolic key resonated with individuals seeking coherence in an increasingly fragmented world. It promised entry into a hidden intellectual heritage, elevating a familiar cultural object into a tool for personal insight and metaphysical exploration. Narrative satisfaction proved stronger than historical accuracy.

Recognizing this process is crucial for anyone approaching tarot critically or creatively. It reveals how cultural artifacts accumulate authority not only through historical continuity but through persuasive reinterpretation. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries supplied the mythic scaffolding that continues to shape most modern tarot practices.

The next phase in tarot’s evolution—the formalization and popularization of these occult meanings through the Rider–Waite deck and related Golden Dawn teachings—will demonstrate how this invented symbolic system became the global standard in the twentieth century.

Leave a comment