When people envision ancient “stargates,” they often imagine machinery—stone rings, luminous portals, or some form of technology inexplicably advanced for its historical context. But this imagery reveals more about modern technological assumptions than it does about ancient epistemologies. We project our own frameworks onto the past and assume that anything powerful must be mechanical.

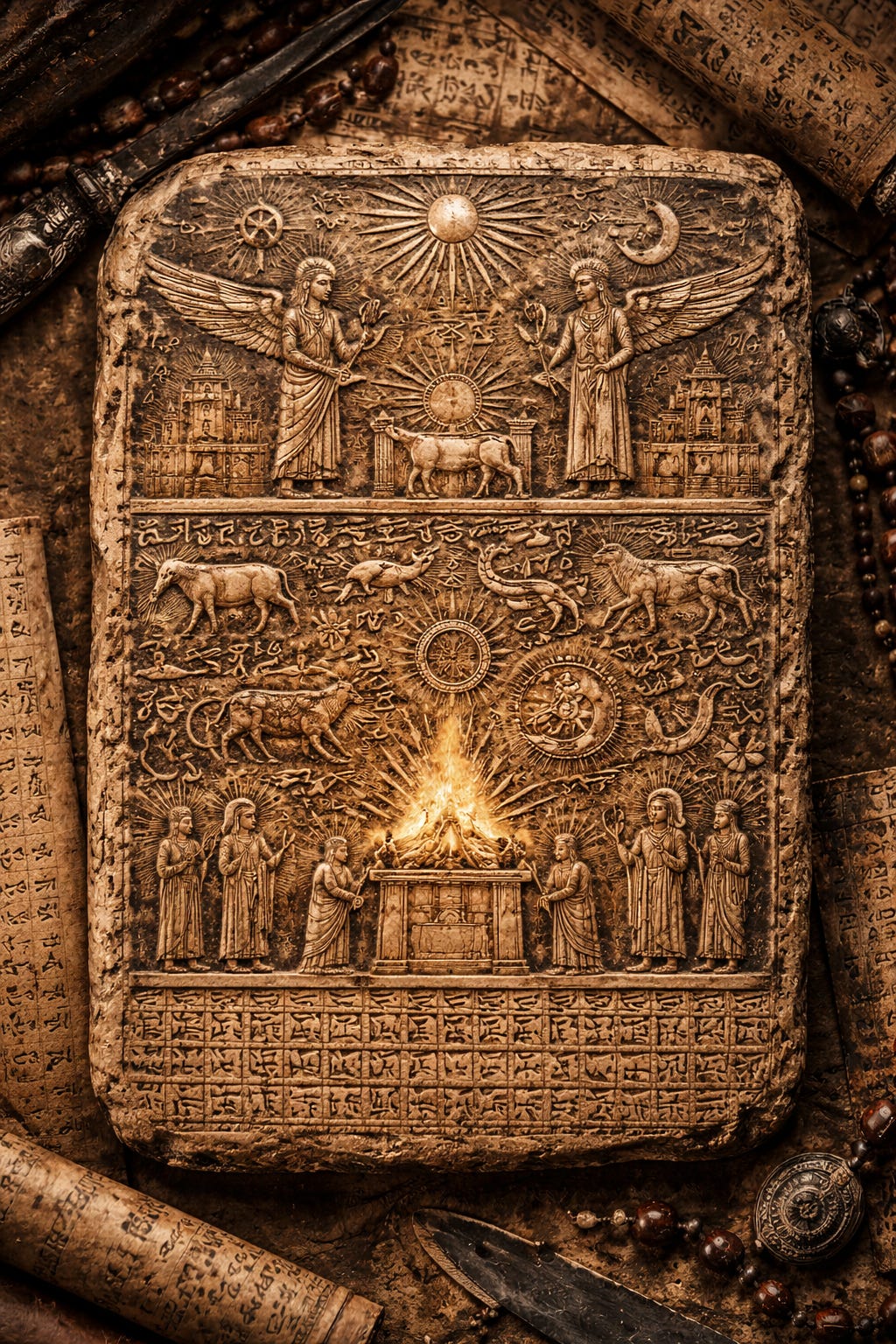

Yet ancient systems were not oriented around machinery. They were oriented around roles, relationships, timing, and interpretation. Power did not come from devices; it came from positions within a structured social and cosmological network.

So the question shifts:

What if the gate was never a machine at all?

What if the gate was a person—a locus of attention, authority, and symbolic gravity through whom events, decisions, and meanings passed? A living interface between the human world and the patterned rhythms of the larger cosmos?

Watching Comes Before Knowing

The earliest complex civilizations were not built on invention first—they were built on observation. Long before large-scale engineering projects or the rise of imperial bureaucracy, societies such as Sumer and Babylon cultivated something more foundational: a continuous, disciplined practice of watching.

They watched the sky.

They watched the seasons.

They watched omens.

They watched economic transactions.

This was not passive attention. It was systematic surveillance—an early form of data collection. The same civilization that recorded planetary movements also maintained meticulous shipment logs, inventories, contracts, and ritual calendars. This overlap is not incidental. A society does not invest effort in documenting both the cosmic and the mundane unless it already recognizes pattern, recurrence, and consequence as the scaffolding of its world.

In this sense, archetypes preceded administration. Conceptual models came first; bureaucracy merely formalized them.

But to understand why this mattered, you have to understand the sky-watching cultures of Sumer and Babylon. Their observational systems were not casual or symbolic—they were continuous, institutionalized, and mathematically sophisticated. The priests of the ēš-gal and ziggurats stood on platforms built not for worship but for measurement. Every dawn, every planetary rise, every eclipse was logged with the same seriousness as a grain shipment or a legal contract.

Over centuries, these records became the first long-term datasets in human history. They allowed Sumerian and Babylonian scholars to detect recurrence: Venus reappearing in predictable cycles; lunar eclipses clustering in the Saros pattern; stars shifting slightly across generations. These were not mystical revelations. They were the first recognition that the world runs on repeatable structures.

The act of watching generated memory—not mythic memory, but empirical memory. Memory hardened into structure: standardized calendars, omen series, administrative cycles, and eventually the machinery of state itself. Structure, in turn, enabled prediction, coordination, taxation, agriculture, ritual timing, and—ultimately—civilizational scale.

Civilization did not grow from tools alone. It grew from the ability to index reality—to map time, encode meaning, and anchor human action inside a patterned world.

Indexing Reality

Ancient omen systems were not “superstition” in the modern, dismissive sense. They functioned as early indexing frameworks—methods for locating the present moment within a broader, continuously shifting pattern of causes, conditions, and consequences. These systems did not attempt to control the world; they attempted to map it.

A bird flies left instead of right.

A star appears ahead of schedule.

A shipment arrives later than expected.

To the ancient observer, these were not magical signs. They were data points—interruptions or anomalies in a network of expected rhythms. Each deviation was meaningful only because it broke from an established pattern. The omen was not the event—it was a signal of one’s current position within environmental cycles, political tensions, or economic pressures.

Sumerian and Babylonian scholars developed entire literatures around this practice. Texts like the Enūma Anu Enlil did not claim that stars or storms caused human events. Instead, they recorded correlations across centuries, forming one of the earliest attempts at long-term probabilistic reasoning. A king consulting an omen record was not expecting prophecy; he was consulting an archive that contextualized the present.

Tarot operates according to the same logic. It is not a predictive device but an orienting one. A draw does not reveal what will happen; it reveals your current placement within a cascade of emerging possibilities.

The underlying insight—that reality behaves less like a linear path and more like a branching field of potential states—was grasped intuitively by ancient cultures long before mathematics provided the vocabulary for describing such systems.

The Gate as a Nexus

Here is where the modern idea of a “stargate” quietly breaks down.

A gate is not something you step through.

A gate is something events pass through.

In ancient systems, the gate was a nexus person—a figure positioned at the center of interpretation, timing, and decision. But more importantly, this person was an oracle, interpreter, or prophet in the structural sense: not someone who predicted the future, but someone who translated the present. They made meaning legible at the exact moment it mattered.

And an oracle never operated alone.

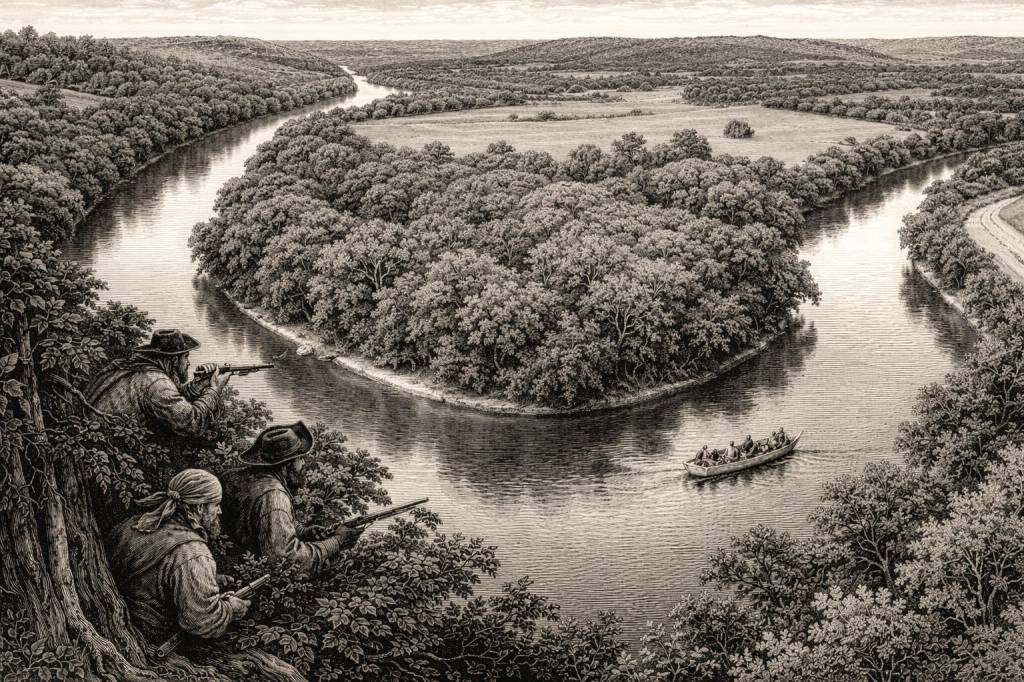

The surrounding figures—priests, attendants, advisors, interpreters, guards, heralds—were not incidental. They formed a functional geometry, an arranged human architecture that shaped what information reached the oracle, how it arrived, and when it demanded response.

This structure is far older than temples or monarchies. Homer himself—”the blind poet”—is a cultural memory of this role. Whether or not he was literally blind is irrelevant. Blindness symbolized something deeper: a person who does not see the world directly, but sees through others. A person whose insight arrives by way of attendants, memory-keepers, reciters, and guides. The prophet stands at the center; the watchers feed them the world.

Think of a pentagram: five points around a center.

A hexagram: six points and a nexus.

Expand further, and you get layered orbits—each circle representing another ring of watchers, interpreters, and filters.

These symbols were not decorative abstractions. They were diagrams of social architecture—maps of how revelation, interpretation, and authority emerged from a coordinated human system.Watchers as Clothing

The watchers did not merely observe the nexus person. They clothed them.

Not metaphorically—operationally.

They filtered information.

They controlled access.

They set timing.

They shaped perception.

In this sense, the nexus person functioned like a processor, while the watchers acted like orbiting shells—much the way electrons determine how an atom behaves.

Change the orbit, and you change the outcome.

This is why ancient rulership, priesthood, and later monarchy were never individual affairs. Power was never personal. It was instrumented.

Watchers as Clothing

The watchers did not merely observe the nexus person. They clothed them.

Not metaphorically—operationally.

They filtered information.

They controlled access.

They set timing.

They shaped perception.

In this configuration, the nexus person operated much like a cognitive processor, while the watchers functioned as the surrounding architecture that determined what inputs the oracle received and how those inputs could be interpreted. Yet even this analogy undersells their historical significance. Watchers were not peripheral assistants; they were the interpretive apparatus itself, the human machinery through which raw experience was transformed into actionable meaning.

Throughout ancient societies, prophets, seers, and poets did not derive authority from isolation. Their interpretive power emerged from a carefully managed flow of information. An oracle’s accuracy—and their legitimacy—depended on the watchers who collected omens, preserved genealogies, communicated disputes, recited histories, and monitored the world for patterns requiring interpretation.

This is why figures like Homer matter so profoundly. The archetype of the “blind poet” is not a biographical detail but a structural position. Blindness symbolized a person who does not perceive the world directly, but perceives it through others—a mediator whose understanding is constructed from the contributions of attendants, reciters, guides, and memory-keepers. The oracle stands at the center, but it is the watchers who supply the universe the oracle must interpret.

Watchers did more than inform the oracle—they shaped what the oracle could know, and what the broader community believed the oracle had the authority to pronounce. They constructed the interpretive field: deciding which signals mattered, which were withheld, and which were elevated into revelation. Alter the watchers, and you alter the oracle. Shift the orbit, and the entire future of the system changes with it.

For this reason, ancient rulership, priesthood, and later forms of monarchy were never truly individual. Power did not reside in the person. It resided in the instrumented system—a coordinated network of perception, filtering, and interpretation operating through a single human node.

Carnival and the Mockery of Kings

Over time, this system did not simply weaken—it fractured, inverted, and re-emerged in distorted form. What survived in public culture was often its parody rather than its principle.

Carnival traditions—especially traveling fairs, midways, and liminal festival cultures—preserved the structure while hollowing out the meaning. Barkers replaced priests. Spectacle replaced ritual. The king, once central to cosmic order, became an object of satire. The rituals of inversion only made sense because earlier cultures had already established the king as the stabilizing axis of the world; the mockery was parasitic on that memory.

But parody only functions when the audience still recognizes the original architecture beneath it. A joke collapses when its model disappears.

This is why Mardi Gras crowns a Rex—because the public still understands, however faintly, that Rex is not merely a mascot but a degraded echo of a ritual king.

Why Hollywood manufactures “stars”—because the public still responds to a central figure surrounded by a constellation of watchers.

Why entourages orbit celebrities with ritualistic consistency—because the geometry of power persists even when its cosmology erodes.

The star system is not casual metaphor. It is the diluted descendant of a much older framework: a human nexus positioned at the center of coordinated watchers, generating symbolic gravity through timing, attention, and controlled access. What looks like pop culture is, in fact, the survival of an ancient operating system—its rituals repackaged as entertainment, its symbolism disguised as spectacle, its watchers renamed as managers, handlers, and agents.

The architecture never vanished. It simply changed costumes.

The Suit That Moves Through Time

When enough watchers orbit a nexus, the structure begins to behave differently—almost as if coordinated attention alters the tempo of reality itself. The presence of many eyes, many minds, and many expectations creates a gravitational field around the central figure.

Decisions compress time. Outcomes amplify. Probability collapses faster.

In this configuration, the group functions like a vessel—not traveling through physical space, but moving through time as a coherent unit of meaning, memory, and authority. The nexus becomes the point through which the entire structure navigates history.

This is where ancient law, ritual garments, and later legal “suits” converge. These were never just rules or articles of clothing. They operated as permission structures—formal containers that stabilized identity, authorized action, and allowed certain individuals to intervene in the unfolding cascade of events. A robe, a crown, a seal, or a legal suit was not symbolic—it was infrastructural. It told the world who was allowed to act, and under what conditions.

A sufficiently instrumented person—someone embedded within these structures—does not move through time like others do. They inherit momentum accumulated by those who held the role before them. They transmit authority forward to those who will hold it next. The individual changes, but the role persists, carrying its influence across generations.

That persistence—this ability for a structure to outlive the person inside it—is the real technology. It is how societies project power across centuries, how institutions survive collapse, and how certain positions continue shaping reality long after their original architects are gone.

Clockwork, Preservation, and Continuity

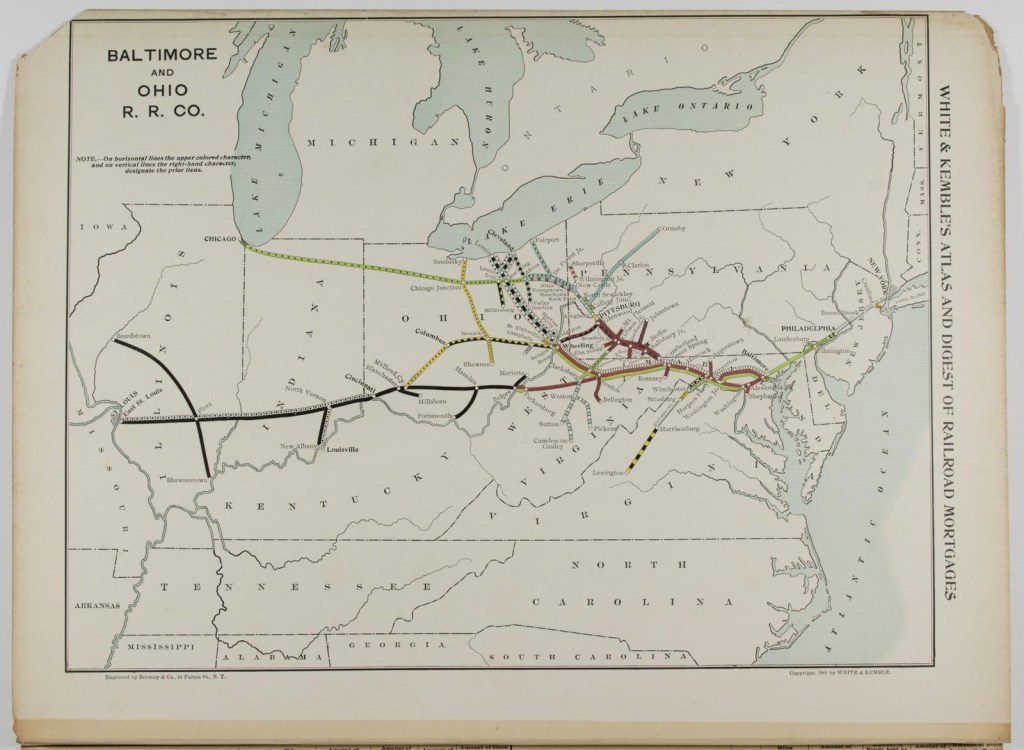

As ancient civilizations fractured or fell, fragments of their interpretive systems survived in unexpected domains: monastic scriptoria, early clockmaking guilds, ritual calendars, legal codes, and administrative traditions. These were not random inheritances. They were repositories for the timing logic that once governed oracular authority.

Precision replaced divination.

Timing replaced omen.

Mechanics replaced myth.

But beneath these transformations, the core principle endured: control the index, and you control the flow. Whoever maintains the timing, sequencing, and interpretive frames ultimately shapes how reality is encountered and understood.

This becomes especially clear when examining the eight‑year Venus cycle, one of the most important temporal structures in the ancient world. Every eight years, Venus returns to almost the exact same position in the sky on the same dates—a phenomenon tracked by the Sumerians, Babylonians, Maya, and later Hellenistic astronomers. This cycle produced the five‑pointed synodic pattern we now call the pentagram.

For ancient timekeepers, this was not astronomical trivia. It was the backbone of long‑count calendars, agricultural planning, coronation timing, ritual sequencing, and divinatory frameworks. Venus’s predictable disappearance and reappearance allowed cultures to anchor human events to celestial rhythms.

And in many societies, Venus was personified as the Virgin, not in the moral sense but in the structural one: a figure whose cyclical return marked renewal, readiness, and the resetting of possibility. The Virgin was a temporal position—the moment when the watchers realigned themselves for the next phase of the cycle.

This is why clockwork cultures mattered—not because they measured time, but because they preserved the authority to structure it. Why political neutrality mattered—not as moral stance, but as a safeguard for custodians of temporal order. Why preservation mattered—not as nostalgia, but as continuity of the architecture.

And eventually, why spectacle mattered. Spectacle became the modern vessel through which timing, attention, and interpretation could be coordinated at scale.

Hollywood did not invent this system. It inherited and inverted it—transforming ritual into entertainment, initiation into grooming pipelines, and ancient watchers into managers, agents, handlers, and publicists. Its power does not come from novelty, but from occupying the same structural position once held by priesthoods and oracular courts.

The mockery works because the architecture remains. A parody cannot persist unless the original structure continues to function beneath it.

The Virgin at the Center

The Virgin archetype is not about purity; it is about unoccupied potential, a position defined by readiness rather than moral quality.

A nexus before activation.

A gate before passage.

A center awaiting orbit.

Like Venus emerging from conjunction, she marks the moment the system resets—when watchers reposition themselves and a new cycle begins. Her significance is temporal: she is the hinge between what was and what will be.

She stands inside the geometry, not above it. She is not divine. She is positional—a structural placeholder whose meaning emerges only when the watchers assemble around her.

She is the gate.

What This Suggests

Ancient cultures did not attempt to engineer mechanical portals. Instead, they engineered interpretive systems—frameworks capable of transforming certain individuals into functional interfaces between the community and the larger rhythms governing their world. An oracle, a king, a poet, a priest—each was a designed position, a point where human perception met cosmic structure.

That knowledge never disappeared. It diffused across centuries, embedding itself in ritual, bureaucracy, monarchy, religious hierarchy, and eventually mass media. Each era repackaged it—sometimes reverently, sometimes cynically—but the underlying architecture endured. Even when mocked, inverted, or secularized, the structure remained intact because culture still needed a way to mediate uncertainty, coordinate attention, and stabilize meaning.

What we call stars, leaders, icons, or chosen figures are not anomalies. They are positions within a system—nodes situated inside an invisible geometry of watchers, timing, expectation, and curated access. These roles do not activate because of personal charisma or destiny. They activate when the surrounding structure aligns around them, when the watchers assemble, when the timing locks into place. The individual is incidental; the position is everything.

This is the uncomfortable implication: the gate was never mechanical.

It was always human—an interface shaped by culture, sustained by watchers, animated by collective attention, and tasked with stabilizing meaning within the flow of time. The ancient world understood this. The modern world has forgotten it. But the architecture still operates, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Leave a comment