By the early twentieth century, tarot had acquired an elaborate symbolic scaffolding built by Enlightenment speculators, Romantic mystics, and the occult societies of Victorian Europe. Yet despite all these reinterpretations, the cards themselves had changed very little. Most readers still used Marseille-style decks with their plain pip cards and medieval iconography. If tarot was to become a genuinely readable system for the modern world—intuitive, accessible, and visually coherent—it needed something more than metaphysical theory. It needed a new language.

That language arrived through the unlikely collaboration of a bookish English mystic and a Jamaican-British artist trained in theater and illustration. Their partnership would quietly reshape the course of tarot history.

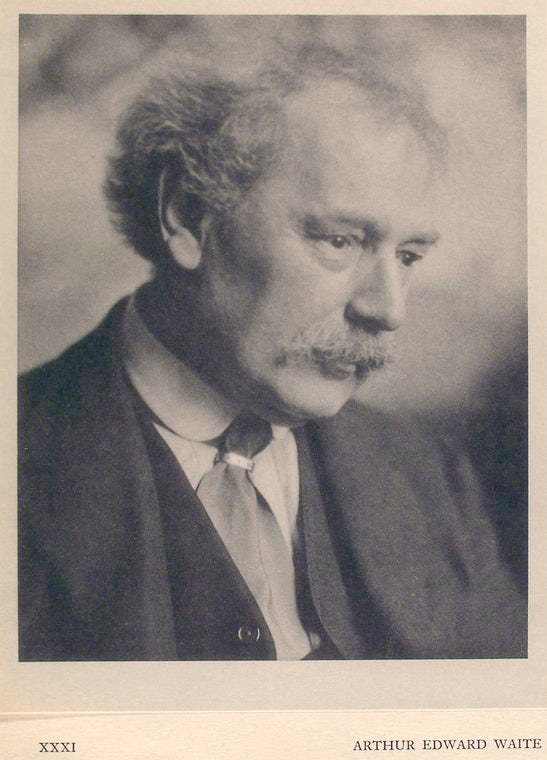

Arthur Edward Waite was, by most accounts, an understated figure—scholarly, methodical, and skeptical of the theatrical currents running through the occult revival. He belonged to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, but unlike many of his contemporaries, he was not drawn to dramatic ritual or magical spectacle. Waite preferred structure. He wanted tarot to express a philosophical system rooted in mystical Christianity rather than the flamboyant magico-sexual frameworks rising elsewhere in the esoteric scene. To him, tarot should be edifying, not sensational.

Pamela Colman Smith, however, possessed a very different temperament. She worked as an illustrator, stage designer, storyteller, and folklorist, moving fluidly between artistic circles. Her sense of visual narrative came not from occult doctrine but from theater—gesture, posture, implied movement, and emotional clarity. Where Waite supplied structure, Smith supplied life. She could take an abstract assignment and make it breathe.

Their collaboration began when Waite, seeking to publish a definitive deck aligned with his Golden Dawn teachings, turned to Smith for the artwork. What he envisioned was a deck that encoded the order’s symbolic system more subtly and coherently than previous attempts. What she delivered was far more transformative.

For the first time in tarot’s history, the minor arcana—the forty numbered suit cards—were illustrated with full scenes rather than simple arrangements of suit symbols. In older decks, a card like the “Three of Cups” would display three cups, nothing more. Smith, by contrast, depicted three women in a circle, raising their goblets in celebration. She gave the cards context, action, and emotional resonance. A simple number became a small window into a human moment.

This innovation changed everything. By turning the minors into narrative images, Smith made tarot legible to readers who were not trained in numerology, astrology, or Kabbalah. Suddenly, the deck could speak visually. It no longer required memorizing correspondences or studying esoteric diagrams. A reader could look at a card and understand its mood, tension, or thematic direction. The deck became a storybook—something one could read through intuition as well as through study.

Waite provided the intellectual architecture, but it was Smith who created the language—the visual grammar that defines modern tarot. Her figures are expressive without melodrama, symbolic without opacity. They stand in landscapes that feel timeless yet grounded, accessible yet rich with implication. The imagery is simple enough to grasp immediately and complex enough to reward revisiting. In this sense, Smith did for tarot what Renaissance printers once did for biblical imagery: she created a standardized visual vocabulary that ordinary people could decode.

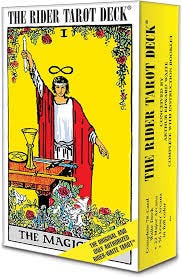

The Rider Company, which published the deck in 1909, lent its name to the project, but the creative force belonged to Waite and Smith. The publisher’s contribution was reach. By releasing the deck widely and affordably, Rider placed tarot in the hands of readers far outside occult circles. Unlike Golden Dawn initiates, these readers were not approaching tarot as a map of cosmic correspondences. They encountered it as a set of evocative images—an illustrated system of human experience.

This shift—from esoteric textbook to accessible visual tool—is what allowed tarot to cross from the cloistered world of magical orders into mainstream culture. Within a few decades, the Rider–Waite–Smith deck became the default framework for tarot interpretation. It influenced Jungian psychology, fueled the mid-century spiritualist revival, and shaped the New Age movement. Most importantly, it standardized the way people learned to “read” symbolic imagery. The deck’s scenes created open space for personal association, inviting readers to project their own memories, questions, and meanings onto the cards.

The irony, of course, is that this most famous of all tarot decks was neither ancient nor mysterious. It was a distinctly modern creation—an artifact of early twentieth-century publishing, artistic innovation, and occult reorganization. It stands at the intersection of mass media, visual literacy, and spiritual curiosity. Its power lies not in hidden lineage but in the effectiveness of its design.

Understanding this history matters because it returns tarot to human hands. The deck is not a relic from lost civilizations but a cultural technology shaped by identifiable people working in a specific moment. Waite sought coherence; Smith provided vision; Rider delivered distribution. Together, they gave tarot the structure and visibility that would define it for the rest of the century.

As we move into the next stage of this series, we will look at how tarot evolved under the pressures of psychology, counterculture, and modern publishing—forces that expanded its reach while often obscuring its origins.